Biography

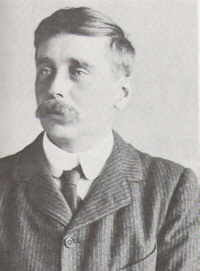

of H.G. Wells (September 21, 1866 – August 13, 1946)

Stories featuring time travel, space flight and alien

invasion are all themes at the very heart of modern science fiction, yet

without the influence of British writer Herbert George Wells, these staples of

the genre might have evolved in a very different and far less entertaining

fashion. That might seem like an awful lot of responsibility to load on the

shoulders of one man, (and indeed other writers such as Jules Verne thoroughly

deserve their place in history) but without a doubt, the present vitality of

the genre is a lasting testament to the original scope and brilliance of Wells'

vision.

The youngest of 4 children, Wells was born to parents

who strived but failed to escape their working class roots. He had a frugal

upbringing, and though never destitute, the threat of outright poverty always

loomed. Prior to the birth of Herbert, his father Joseph had been a gardener

and his mother Sarah a ladies maid, but subsequently a failed venture in a

Bromley crockery shop (above which Wells was born) almost bankrupted the

family. Only his fathers earnings as a professional cricketer kept the wolf

from the door, but even this was curtailed when he was disabled in a fall.

Under these circumstances, Herbert's mother was forced to return to domestic

service, and the teenage Wells began a series of unsuccessful encounters with

the world of work. Several attempts to follow in the footsteps of his brothers

and become apprentice to a draper (which he hated) came to nothing, as also did

an apprenticeship to a chemist. It was only by a combination of luck and his

innate intelligence that allowed Wells the opportunity to escape from this

intellectual cul-de-sac.

At the age of 18, after a period as a teacher/pupil at

An accident on the football field took a tragic turn,

when at the age of 21, Wells lost a kidney. For a time he became a semi invalid

and at roughly the same time his interest in his schooling faltered, though at

the same time, these circumstances almost certainly influenced his

determination to be a writer. In 1887 he left the

By 1893 Wells had made the transition to a full time

writer and had penned his first book, the nonfiction "Textbook of

Biology". However, this was not to be an entirely happy time, for his

marriage was swiftly faltering and in 1894 Wells ran off with a former pupil

named Amy Catherine Robbins. She was to become his second wife in 1895. That

same year also saw the publication of his first science fiction novel, The Time

Machine: An Invention, the genesis of which had actually been The Chronic

Argonauts, a three part speculative series he had written in 1888 for the

amateur publication, The Science Schools Journal. Three years later, a second

version was published in the Fortnightly Review, where it was known as The

Rediscovery Of The Unique. It was almost printed again in the same periodical

as The Rigid Universe, but even though it was set in type, it was never

actually published. However, parts were eventually serialized in issues of the

New Review for 1894-95. Finally, after this long gestation, Wells sold the

completed story for

Though not the first writer to toy with the idea of a

fourth dimension (Jean d'Alembert postulated one in his 1754 article

"dimension"), the success of The Time Machine served to popularize

the concept, with Wells sending his traveler on a fantastic voyage into the far

future and landing him penultimately in the year 802701. Here the influence of

Huxley and Darwin can be seen, as the traveler discovers that the human race

has evolved into two distinct species, the brutal and animal-like Morlocks and

the gentle but feeble Eloi. Most uniquely, the novel was the first to propose a

mechanical method of time travel, a breathtaking leap of imagination that has

served as a blueprint for hundreds of stories since.

Yet there is even more to the story than this, for

Wells was also using his science fiction as a metaphorical device. The Eloi

were essentially the degenerate ruling class, living a life of bucolic

ignorance, while the Morlocks were the workers, condemned to live in stygian

darkness. However, Wells cleverly turns the tables on the prevailing social

order of his time, for the Morlocks are not the underclass they at first seem,

but instead maintain the apathetic Eloi as their food stock. Escaping this

nightmare scenario, the traveler eventually arrives in the year 30,000,000,

where he finds the earth a cold and lifeless world; not the first, but

certainly one of the earliest and most vivid accounts of an entropic end to all

things.

The basic principles of a fourth dimension Wells laid

out in The Time Machine would predate the work of Albert Einstein, but he was

also a crusader against social injustice, using his fiction to mirror the

inequities he saw about him, as well as to comment on the dangers of unchecked

scientific process. Wells would expand on this latter theme graphically in The

Island Of Dr. Moreau, (1896) telling as it does of a scientist who has

surgically altered the jungle beasts of his isolated island into mockeries of

the human form. This is principally a dissertation on the nature of man. Moreau

is attempting to "humanize" the animals, but always the nature of the

beast creeps back into his creations, frustrating his goal. Eventually they

turn on their tormentor, and he is killed. Wells chose vivisection as the

method Moreau employs to mould his creatures, but the novel is an obvious

precursor to the concept of genetic engineering, and indeed successive movie

versions of the story have updated the story to take into account these

scientific advances.

In The Invisible Man, published the following year,

Wells further examined what might happen to a man who is granted a power that

sets him above other men and the moral corruption that ensues. Once again, it

is a scientist who has stepped beyond the bounds, in this case inventing a

process that turns his body invisible. As the novel opens, the scientist has

already experimented on himself, and arrives in a small rural community, his

head swathed in bandages to disguise his terrible secret. Rather than see his

invention as a boon for all mankind, the scientist is swiftly descending into

madness, and confides in a local doctor his plans for a reign of terror for his

own personal gain. The Faustian warning is plain, that science is capable of

infinitely more harm than good.

In 1898, the noted scientist Percival Lowell was observing

what he took to be artificially created canals on the surface of Mars, a theory

that quite captured the public imagination of the time. Perhaps influenced by

these events, (and certainly because of German unification and rumblings of a

pan-european war) Wells would that same year create one of the most powerful

concepts in the field of science fiction. What if there were indeed life on

Mars, in fact intelligent creatures technologically far in advance of our own

world, and what if those creatures were hostile?

In The War Of The Worlds (1898), Wells conceived just

such a species. Forced to flee their own dying world, his Martians attempt to

make a home on earth by force of arms, landing in an ill-prepared Victorian

England, where they begin a devastating reign of terror. Sweeping aside all

resistance in their tripod legged war machines, the Martians lay waste to the

snug Victorian way of life. It is in fact the way that Wells creates a feeling

of the calm before the storm, describing an idyllic

Like everything he wrote, there are some clear

underlying themes, not least that Wells was dishing out a little of our own

medicine, asking in effect, "how do you like to be at the receiving end of

a very large stick, just as many real people had genuinely suffered under the

British colonial yoke? In fact, it was a conversation with his brother Frank

about the fate that had befell the Tasmanian peoples when they were discovered by

the Europeans that Wells himself quoted as a spark for the novel. One can also

see a stark message in the way the Martians are vanquished, suggesting as it

does that science is not necessarily going to be the saviour of mankind and

that in fact we would do well to remember that nature at the most microscopic

level can be every bit as powerful.

One of the last major works of science fiction to be

produced by Wells nevertheless introduced another seminal concept into science

fiction, that of an alien species where cooperation and unity of purpose are

the driving force of their society. The First Men On The Moon (1901) also saw

Wells postulating, in essence, an antigravity drive, though the pseudo-science,

while entertainingly presented, is secondary to the real message of the novel.

A spaceship propelled by Cavorite, a material opaque to gravity is dispatched

to the moon, and there the crew discover an extraordinary ant-like society,

whose guiding principles might almost be said to be Socialist in nature.

Contrary to the nature of so many of his novels, Wells

not only had obvious socialist leanings (clearly he detested social inequity),

but he was also a vocal utopian, believing that man could achieve a blissful

existence on earth. However, the lot of man did not improve in his lifetime and

more and more he wrote despairingly of the dangerous use of science in warfare.

For instance, The Land Ironclads (1903) again saw Wells in prophetic mood,

predicting the coming of tank warfare, and in 1908 he wrote of a catastrophic

aerial war in The War In the Air. He lived to see both of the above predictions

come tragically true, but perhaps his greatest and saddest speculation

concerned the use of Atomic weapons. In The World Set Free, he wrote,

"Nothing could have been more obvious to the people of the early twentieth

century than the rapidity with which war was becoming impossible. And as

certainly they did not see it. They did not see it until the atomic bombs burst

in their fumbling hands." Those lines were written in 1914, and Wells

lived just long enough to see their use in

Biography of H.G. Wells 29-10-08

http://www.war-ofthe-worlds.co.uk/h_g_wells.htm

© John

Gosling

More biographies [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

Academic year 2008/2009

© a.r.e.a./Dr.Vicente Forés López

© Aina García Coll

aigari@alumni.uv.es

Universitat de València Press