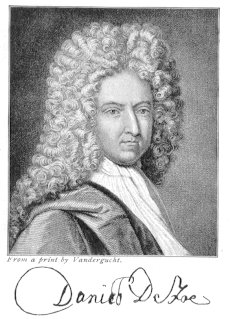

By the time he took up his pen to write Robinson

Crusoe at about the age of fifty-eight, Daniel Defoe had a broader range

of experiences behind him than most can claim for a lifetime. At one time

or another he was a merchant, a manufacturer, an insurer of ships, a convict,

a soldier, an embezzler, a spy, a fugitive, a political spokesman. And

of course, an author.

Defoe's life was, to say the least, a strange one.

He was born Daniel Foe to a family of Dissenters in the parish of St. Giles,

Cripplegate, London; his exact birth date is unknown, but historians estimate

that it was in the year 1659 or 1660. (Why Daniel added the "De" to his

surname is a subject of speculation. He might have decided to return to

an original family name. Maybe he wanted to give himself a high-born cachet.

In any event, in his mid-thirties he began signing his name as Defoe.)

James Foe, his father, a butcher by trade, was a sober, deeply pious Presbyterian

of Flemish descent--one of perhaps twenty percent of the population that

had relinquished ties to the main body of the Church of England. Very little

of known of Daniel's childhood. However, it is reasonable to assume as

the son of a Dissenter much of his time was spent in religious observances.

It is likely that this spurred the fervent belief in Divine Providence

that is so evident in his writings. Since they were barred from Oxford

and Cambridge universities, Dissenters sent their children to their own

schools. Defoe's education began in the Rev. James Fisher's school in Dorking,

and later, at about the age of fourteen, he was enrolled in the Dissenting

academy in Newington Green. Newington's headmaster, Rev. Charles Morton,

a plain-spoken Puritan, was a progressive educator (despite a belief in

storks spending the winter on the moon). He gave his students a thorough

grounding in English as well as the customary Greek and Latin. Morton is

seen as a major influence on Defoe's writing style; the other influence

was the Bible.

Although intended for the ministry, Defoe settled

instead on a career as a commission agent. For more than a decade he traded

in a wide range of goods, including stockings, wine, tobacco, and oysters.

Trade was a loved subject of this man. He wrote countless essays and pamphlets

on economic theory which were advanced for his time. Indeed, had he taken

his own advice, he would have been a wealthy man. While his years as a

broker endowed him with insight into human nature, his risky and unscrupulous

ventures (he was sued at least eight times, and once bilked his own mother-in-law

out of four hundred pounds in a cat-breeding deal), combined with bad luck

and faulty judgment, more often than not steered him into debt, deceit,

and political double-dealing. Still, in his mind and heart, Defoe undoubtedly

saw himself in the role of solid, middle-class family man. He wrote numerous

treatises which demonstrated that he considered himself an expert on most,

if not all, family matters. However, his own marriage to Mary Tuffley,

a merchant's daughter, despite its length of forty-seven years and fecundity

of eight children, cannot have been a model of matrimonial paradise. Defoe's

unstable fortunes, his extended visits abroad, and his absence while a

fugitive from enemies and creditors would have tried the patience of the

most patient, loving spouse. There is evidence also that, in spite of loving

them deeply, Defoe alienated some, if not all of his children. A year after

his marriage, Defoe took up arms as a Dissenter in Monmouth's failed rebellion

against the Catholic King James II. Unlike three of his former classmates

who were caught and sent to the gallows, Defoe narrowly missed the troops

and hastened to safety in London. When the king was deposed, Daniel rode

with the volunteer guard of honor that escorted William of Orange and his

wife Mary into the city.

Due mainly to losses incurred by insuring ships

during a war with France, Defoe faced bankruptcy in 1692. With creditors

hot on his trail he fled to a debtor sanctuary in Bristol, and from there

was able to negotiate terms that spared him the humiliation of debtor's

prison. Within ten years he had repaid most of what he owed. Unfortunately,

Daniel never fully recovered from that fiasco. Debt would haunt him as

long as he lived. This circumstance can be credited for his ambivalent

political actions and his prodigious output as a writer. He was able to

win King William's favor, and was appointed Commissioner of the Glass Duty.

He was put in charge of proceeds from a lottery and became the king's confidential

advisor and leading pamphleteer. Defoe's fervent sense of justice often

led him to tweak the noses of those in high places. His essay, The Shortest

Way, would bring him great grief. A satire that poked fun at the manner

in which the Church and State dealt with Dissenters, it infuriated the

powers at large and forced Daniel to go into hiding. He was betrayed by

an informant and brought to trial for "seditious libel against the Church."

He was jailed and sentenced to three days in the pillory, a manacle device

that exposed a criminal to public ridicule.

A pardon some months later from Queen Anne hardly

was a chance to start over. Defoe's tile and brick business had fallen

apart during his absence, and he once again faced debtor prison. A grant

of 1000 pounds from the Earl of Oxford allowed Defoe to climb out of debt

and start his own newspaper, the Review. He ran his views and was frequently

in trouble for them. After another arrest in 1715 for libel, Defoe spent

his time covertly editing other newspapers as he worked on novels such

as Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. He died in 1731, poor and fighting.

To see the chronology click here.

Copyright © 1999-2000 Not affiliated with Harvard College

Academic

Year 00-01

07/02/2001

©a.r.e.a.

Dr. Vicente Forés López

©Ana

Aroa Alba Cuesta

Universitat

de València Press