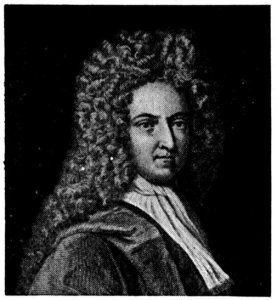

daniel defoe's biography

Pope notwithstanding, the beginning of the century is primarily a prose- writing period and its most memorable works are in prose. The art of circulating facts and ideas among an ever-increasing public had by now made considerable progress.

The work of Daniel Defoe (1660-1731) is very characteristic in this respect. Defoe was a journalist whose genius is the more astonishing because he had to invent almost the whole of his craft.

Before him there had indeed been several more recent publications, besides many papers in the Civil War times, which corresponded to the newspapers of our day. Sir Roger L’Estrange with his Observator (1681-7) and John Dunton with his Athenian Gazette(1690-6) have the credit attached to precursors, but it was Defoe who really widened the new path in 1704 with The Review, which he conducted until 1713. He had not indeed waited until then to address the public. He was both a man of letters and a man of action. The son of a dissenting butcher, he received a modern education, completely practical and quite unlike that supplied by the universities; dead languages were replaced by living: scholasticism and metaphysics by history, geography and politics. Defoe began his career as a Hoosier; hewas an ingenious but rash a tradesman and ended by going bankrupt in 1602. He obtained his discharge, however, and continued in business as manager of a tile-works. But he was already tormented by the itch to write. The revolution of 1688 put William III, a protestant King after Defoe’s own heart, on the throne. He was a completely devoted subject, and it appears that he king recognised his zeal and sometimes had recourse to his sagacity. It was to defend this king, of whom many were suspicius because he was a foreigner, that Defoe wrote his first really popular work: The True-Born English Man (1701), a long satiric in prosaic but clear an d vigorous verse in which the author showed how the English nation was itself made up of the most diverse elements, and that it was ungraciousness on its part to condemn the King for not being of pure English stock. Already Defoe was showing himself skilful in the handing of arguments likely to appeal to the multitude. His second widely known production was The shortest way with the dissenters (1702) in which he took upon himself to defend the dissenters against the rigorous measures avocated by the Anglicans. To produce a greater effect he made his attack obliquely, putting his words into the mouth of a distinguished anglican, an imaginary personage who demands outright that the dissenters shall be surppressed by being sent to the gallows; and such was the inperturbable gravity of his irony that his co-religionists read it with terror and his enemies with approval until they discovered that they had been fooled. the outcome was disastrous for defoe, who was thrown into prision and set in the pillory; the people, however, regarded him as a hero.

Ruined once more and undesirous of running futher risks, the defoe became a journalist and was patronized and secretely paid by the tory minister Harley. He was looked upon, apparently, with justice, as a secret agent of those who had been the bitter enemies of his party. Nevertheless he seems to have continued to express the moral and economic deals so dear to him. His knowledge of foreing countries and his travels through every p'art of england and scotland made him a very prudent counsellor who was well acquainted with the state of mind of the people.

It was only late on life, when he was near his sixtieth year, that he began the series of imaginative stories that constitute the first english novels, Robinson Crusoe heading the list. They all took the form of memoirs or pretended historical narratives, in which everything was designed to give the impression of reality. even where extraordinary adventures abounded, Defoe succeeded in avoiding any appearance of the fantastic, of the invention, or of artistic arrangement on the part of the author. the total supression of art -taht is, of apparent art- was made easier for him because he had no taste for beauty ot to what he conceives to be beatiful. Defoe took no account of it. His only purpouse was to make his stories so lifelike that the reader's attention would be fixed solely on the events. these would, moreover, be the more readilyaccepted in proportion as they were vouched for by a greater number of details and as these details looked at one by one were more ordinary, more everyday, more completely stripped of a esthetic significance. It was in this way that Defoe carried to the highest perfection the only art cultivated, the art of lying.

In this respect he presents a striking analogy with the author of gulliver, but if swift deceives for a moment he is in the end betrayed by his humour, and indeed he does not seek to deceive indefinitely. Defoe, on the contrary, hides his own part so well that the illusion persists to the end, and it was for a long time impossible and is even now difficult to distinguish in some cases between his false reminiscensces and his true ones. For his multiplication of details defoe fell back on his varied experiences of trade and of everything connected with the practical conduct of life. He justified the boldness of his tales by his design of reporting faithfully and also of inculcating a moral lesson. At bottom his books were meant to satisfy the same curiosity about out-of-the-way adventures and the disreputable careers of thieves and prostitutes as Robert Green's "cony-catching" pamphlets. the chief cahnge is in the mannerand in the style, which rejects all ornament and all subtlety, content to be perfectly precise and practical.

these characteristics are common to all defoe's fictions: Moll flanders, the life of a prostitute, Roxana, the life of a great cortesan, memoirs of a cavalier, the life ofcaptain george carlton, the life of captain singleton, a journal of the plague year (i.e. 1665), the life of john sheppard, the highwayman, the history of colonel jacque, another highwayman, and the rest.

Robinson crusoe, is one of those numerous accounts of imaginary voyages in which defoe delighted. crusoe's sojourn on a desert island, which has become a tale of universal appeal, occupies the middle part of the work. without Relaxing his workaday manner, Defoe was fortunate enough to hit upon a theme that teases the imagination -the life of a man separated from his fellows and obliged to provide for his own physical and spiritual needs. No invention of a poet could operate with such irresistible effect on the imagination of all ages and of all times.

there was no contemporany writer who so broadened the basis of literature as defoe, or appealed to so wide a circle of readers- to all, in fact, who were able to read. but he himself, in the eyes of men of letters, was outside of literature. Neither pope nor swift looked upon him as a literary man. this disdain was justified by his career, equivocal to say the least, as a phamphleteer, but it was founded also in his rejection of the whole tradition of humanism to which the other prose-writers of the period, steele, addison, swift, arbuthnot, and the rest, were attached. even when they aspired to popularity, they still respected the literary code bequeathed by antiquity and revived by the renaissance.

they obeyed principles of composition and conventions of style derived from their classical education. instead of reproducing, like defoe, the modes of speech and writing of common people with intelligent but uncultured minds, they introduced into their style even at its simplest an elegance and art which raised their writings a setp above the language of every day. they chose their words, they preferred certain turns of phrase for their distinction, they adorned their pages here and there with some figures of speech or comparison . Even when they renounce all artifice one feels that they have studied rethoric with profit. and all these things determined the limits of their public. the common people, to whom defoe addressed himself, formed no part of it. they aimed rather at instructing the middle classes, the honest citizens who wished to cultivate both their intelligence and their style, who demanded decency of conduct and a certain amount of elegance of expression.

the periodicals of steele an addison do not rely for their attraction on news of political happenings; they are so many pleasant essays on practical moral questions, reflecting the manners of the time by means of numerous anecdotes of the most varied kinds.

THIS TEXT IS AN EXTRACT OF THE BOOK: "A SHORT STORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE" BY ÉMILE LEGOUIS.

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS.

THE INFORMATION IS PLACED IN THE PAGES 206-210.

©Cristina Escutia Sanchis