3. Enemies of the Free Peoples of Middle-Earth or historical enemies of Western Europe?

A hypothesis had been arisen that Tolkien had racist ideas he unveiled in his work. As some saw a nazi behind each orc, the phisiology of the elves fed doubts on why the "good" were tall and blond and the evil were small, ugly, dark and deformed. And no point since the film showed them so. Concerning this podrían escribirse tomos enteros y sacarse miles de conclusiones, pero no hace falta ir tan lejos, en primer lugar si consideramos a Tolkien un estudioso proto-germánico y buscamos argumentos que validen esta idea. El mismo autor nos lo clarifica en una de sus cartas a su hijo Michael:

I have spent most of my life, since I was your age, studying Germanic matters (in the general sense that includes England and Scandinavia). There is a great deal more force (and truth) than ignorant people imagine in the "Germanic" ideal. I was much attracted by it as an undergraduate (when Hitler was, I suppose, dabbling in paint, and had not heard of it), in reaction against the "Classics". You have to understand the good in things, to detect the real evil. But no one ever calls on me to "broadcast", or do a postscript! Yet I suppose I know better than most what is the truth about this "Nordic" nonsense. Anyway, I have in this War a burning private grudge - which would probably make me a better soldier at 49 than I was at 22: against that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler (for the odd thing about demonic inspiration and impetus is that it in no way enhances the purely intellectual stature: it chiefly affects the mere will). Ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light.

Tolkien & Carpenter, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 55

As it can be seen in this excerpt, Tolkien had his own reservas y predilections, and once again the problem when interpreting him came from the context he lived in. It is not the aim of this section to clarify how deep did nazism got into Norse mythology and the philosophy of Nietzsche, but it would be interesting enough to observe that like Nietzsche was considered a godfather to nazism AFTER Nationalsocialistic ideologists manipulated his thoughts, some others may have put Tolkien also in the same shelf after filtering him through nazism. He and Hitler were contemporaries, but all that Tolkien loved so much came from a lot earlier in time, and nazis had manipulated it, while he fought to preserve it in its original shape.

Even if someone earned for more on the opposite, they'd have fun enough to enjoy when finding this excerpt from a letter to his son Christopher, in which in addition to imaginary monsters, Tolkien talks about corrupted people and his hatred for the rawness of a certain landscape:

Urukhai is only a figure of speech. There are no genuine Uruks, that is folk made bad by the intentions of their maker; and not many who are so corrupted as to be irredeemable (though I fear it must be admitted that there are human creatures that seem irredeemable short of a special miracle, and that there are probably abnormally many of such creatures in Deutschland and Nippon - but certainly these unhappy countries have no monopoly: I have met them, or thought so, in England's green and pleasant land) All you say about the dryness, dustiness and smell of the satan-licked land reminds me of my mother; she hated it (as a land) and was alarmed to see symptoms of my father growing to like it.

Tolkien & Carpenter, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 90-91

If we stop reading just at “…Nippon…” on the above quotation, it looks as if the creatures were corrupted German and Japanese people, very numerous in their countries. But if we keep on reading we may notice that even in the peaceful core of England there are monsters, so no part of the world is safe from the presence of evil creatures and any man could be a victim of corruption. We can't tell whether Tolkien speaks either in irony or really in pity, referring to them as unhappy countries. Unhappy because they always count on such inhuman beings as their population (for what there is no fix) or because it is a temporary state in which they are at now (and have to cope with until it ends). We can't neither be sure about which place is Tolkien refering to with “satan-licked land”, though some hints are given 'between-the-line'. The land is the place where Christopher was right then ('All you say about' indicates that), and according to the chronology, he was at the front in Africa. And as long as he affirms that he and his mother hated it and his father was growing to like it, it is possible that they could be talking about Africa. It was the land that took his father away from him, so to a certain extent his refusal would be logical. However, in spite of it, in a previous letter Tolkien affirmed that he kept beautiful visual memories of both Africa and England:

Some of my actual visual memories I now recognize as beautiful blends of African and English details...

Tolkien & Carpenter, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 85

In another letter, in which he confesses he belongs to the losers' side, Tolkien talks about his dislike of the Roman Empire, where he would had rather been an apparent patriot with secret thoughts about the freedom and supremacy of the enemies of Rome:

However it's always been going on in different terms, and you and I belong to the ever-defeated never altogether subdued side. I should have hated the Roman Empire in its day (as I do), and remained a patriotic Roman citizen, while preferring a free Gaul and seeing God in Carthaginians.

Tolkien & Carpenter, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 89

Visual format offered in the film could, up to a certain point, raise suspicious equivalences between Tolkien’s viewpoints and the looks of the enemies of the Free Peoples on the screen. The Haradrim tribes, according to film-dressing, are suspiciously similar to those of the Tuaregs, Berbers or Beduines. The corsairs of Umbar are Turkish pirates. Easterlings have looks halfway between Roman centurions and Japanese samurai. Men from Far Harad riding the Oliphants are a mixture between African and Austral indigenous people and Indians; oliphants are exotic creatures, strange and mastodontic, facts which remind of 18th and 19th century adventure literature in the narrative mood of Sir W. Scott, R. L. Stevenson and Verne. Putting together the looks of the film and Tolkien’s strong christian beliefs, one could make a picture that somehow The Lord of the Rings is a story on the crusade of christianism and Western society against all its natural or historical enemies: romans, carthaginese, barbarians, arabs, muslims, turkish, mongols or japanese.

3.1 Easterlings, Roman Soldiers and Samurai Warriors

Left to right, a capture of Easterling troops marching towards the Black Gate of Mordor, a Japanese Samurai armor dating from 1860, and Roman troops: a scheme of a general and a soldier in combat armor.

Whether Tolkien intended his tribes being recognisable or not, they started getting a shape, firstly from illustrators and later on by the magic of the movies, and of course they had to come from somewhere. In the above set of pictures we can notice similarities between Easterling's armor and those from a Japanese Samurai and two Roman soldiers: full-head winged helmets, iron and leather body armors and large square shields. Tolkien may have been a good Roman and found monsters in the Far East, but the film required physical representations which casually coincide with some of his opinions.

3.2 Haradrim and Southrons

There is a very interesting question concerning the inhabitants from Far Harad. They are generally given the name Haradrim, but there are al least three varieties of them. The strict Haradrim are those who look like desert nomads, or touaregs. The oliphant riders, though coming from the same region, are called Mahűd, fierce hunters and elephant tamers, halfway between elephant-guides from India and African warrior tribes. And there is yet another tribe inside the Harad, the Hâsharin, resembling Arab hashshashin (not much for the ethimology of the word as for the story), the first hitmen in history, coming from a sect within the Ismaili Muslims. This last tribe does not appear neither in the book nor in the film, but it dates from the first alliances of Sauron with Eastern Men related in The History of Middle Earth (Vol.III)

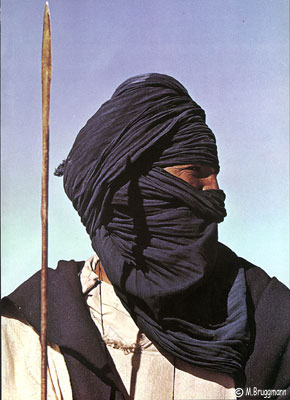

Touareg shepherd Extra in set dressed like one of the warriors from Far Harad

Almost the same person, but the one on the left is the real touareg, and the man on the right is an extra in a set. Muslims have been the pretended natural enemies of Christendom through history. Tolkien was not of course calling contemporary Muslims our enemies, but maybe depicting his own revision of the Crusades or describing tribes directly inspired by the exotism of colonial literature. Some may say the cause for this could be easily found in his biography, but we must remember that he lived in Bloomfountein for a short period, and it was in civilised Africa, NOT in the middle of Sahara Desert, in addition to the fact that as we have seen his memories about it were quite grateful.

3.3 Oliphaunts and Riders

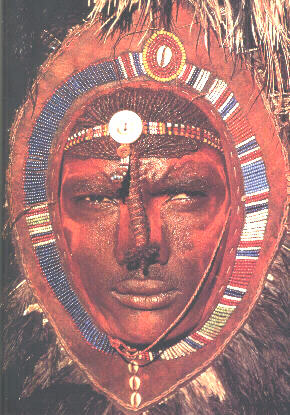

Left to right, a Masai warrior, a Fijian warrior and one of the Mahűd chieftains riding an oliphaunt. All of them wear their customary war-paint.

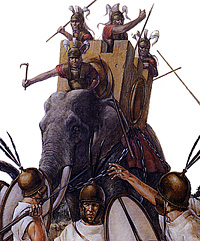

A still from the film; a Műmakil on its way to Gondor, as seen by Sam from the top of a hill. Next to it, an illustration for the attack one of Hannibal's elephants to Carthaginese soldiers. The resemblances are obvious, for both are great elephants carrying a turret on their back, though in spite of their name, oliphants look more like prehistoric mammoths. The oliphaunts in the film are not Jackson's version, for their description was provided by Tolkien through the eyes of Sam:

To his astonishment and terror, and lasting delight, Sam saw a vast shape crash out of the trees and come careering down the slope. Big as a house, much bigger than a house, it looked to him, a grey-clad moving hill. Fear and wonder, maybe, enlarged him in the hobbit's eyes, but the Műmak of Harad was indeed a beast of vast bulk, and the like of him does not walk now in Middle-earth; his kin that live still in latter days are but memories of his girth and majesty. On he came, straight towards the watchers, and then swerved aside in the nick of time, passing only a few yards away, rocking the ground beneath their feet: his great legs like trees, enormous sail-like ears spread out, long snout upraised like a huge serpent about to strike. his small red eyes raging. His upturned hornlike tusks were bound with bands of gold and dripped with blood. His trappings of scarlet and gold flapped about him in wild tatters. The ruins of what seemed a very war-tower lay upon his heaving back, smashed in his furious passage through the woods; and high upon his neck still desperately clung a tiny figure-the body of a mighty warrior, a giant among the Swertings.

Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, 646-647

Tolkien himself talked about this particular incident with the Műmak in one of his letters to his son Christopher:

A large elephant of prehistoric size, a war-elephant of the Swertings, is loose, and Sam has gratified a life-long wish to see an Oliphaunt, an animal about which there was a hobbit nursery-rhyme (though it was commonly supposed to be mythical)

Tolkien & Carpenter, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, 77

After that, Tolkien quotes the nursery-rhyme sung by Sam, but the description of the Oliphaunt is much more 'romantic', just about its size and might, and not about its uses at war.

© 1996-2006, Universitat de Valčncia Press

© Ignacio Pascual Mondéjar, 2006

© a.r.e.a. & Dr.Vicente Forés