ENGLISH POETRY XIX-XX

ROSSETTI BROTHERS, A REFERENCE

IN VICTORIAN POETRY

ROSSETTI BROTHERS, A REFERENCE

IN VICTORIAN POETRY

In poetry, talking about Rossetti is

talking about two of the most important poets in the Victorian Era, Dante

Gabriel Rossetti was one of the references of the 2nd period of the 19th

century and Cristina Rossetti was one of the most important poet women in

England.

First, let’s learn something about their lives and work, also

about their importance in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, then we will see their poetry through the analysis of two of their works.

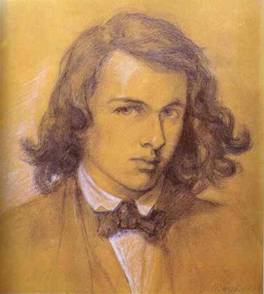

“Gabriel Charles Dante

Rossetti, who later changed the order of his names to stress his kinship with

the great Italian poet, was born in London May 12, 1828, to Gabriele and

Frances (Polidori) Rossetti.

Dante attended

King's College School from 1837 to 1842, when he left to prepare for the Royal

Academy at F. S. Cary's Academy of Art. In 1846 he was accepted into the Royal

Academy but was there only a year before he became dissatisfied and left to

study under Ford Madox Brown. In 1848 he, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett

Millais began to call themselves the Pre-Raphaelite

Brotherhood. This group attracted other young painters, poets, and

critics; William Michael Rossetti acted as secretary and later historian for

the group.

In 1849 and 50

D.G.R. exhibited his first important paintings, The Girlhood of Mary Virgin and Ecce Ancilla Domini (illustration). At about the same time he met Elizabeth Eleanor

Siddal, a milliner's assistant, who became a model for many of his paintings

and sketches. They were engaged in 1851 but did not marry until 1860, perhaps

because of her ill health, his financial difficulties, or a simple

unwillingness to undertake the commitment.

A commission to

cover the walls of the Oxford Debating Union with Arthurian murals introduced

Rossetti to William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and A.C. Swinburne in 1856 and 57. While there he also met index Burden,

with whom he fell in love, and introduced her to Morris, whom she married in

1859. After an engagement lasting nearly ten years, Rossetti and Lizzie Siddal

were married barely 20 months before she died from a self-administered overdose

of morphia on February 10, 1862. Although suicide was suspected, the coroner

generously decided that her death was accidental.

After her death

Rossetti moved to 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, a large house

on the Thames which he shared with Swinburne and also (occasionally) his brother William Michael

Rossetti and George

Meredith . He continued painting and writing poetry, gaining patrons enough to

become relatively prosperous. Another of his models, Fanny Cornforth (who

appears in Bocca Baciata, The

Blue Bower, and Found ), became his mistress

and housekeeper, but because of her full-bodied blondness, never one of his

idealized women. That role was filled first by Lizzie Siddal; occasionally by

models like Ruth Herbert and Annie Miller; but most famously by Janey Morris.

Rossetti's choice of models and his idealization of them helped change the

concept of feminine beauty in the Victorian period to the tall, thin,

long-necked, long-haired stunners of frail health that we see in paintings like

Beata Beatrix, Pandora, Proserpine, La Pia, and La Donna della Finestra. The

persistence of the Pre-Raphaelite ideal shows up in photographs of William

Butler Yeats' idealized beauty, Maud Gonne. Jack Yeats, the father of the poet,

was connected with the Pre-Raphaelites, and Yeats himself said of his younger

days, "I was in all things Pre-Raphaelite." In 1871 Rossetti and

Morris leased Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, and Morris visited Iceland,

leaving Rossetti together with Jane and her children. Although biographers

still argue about what exactly went on among them, the triangle was in any case

a difficult situation for all concerned.

In the late '60s

Rossetti began to suffer from headaches and weakened eyesight, and began to

take chloral mixed with whiskey to cure insomnia. Chloral accentuated the

depression and paranoia latent in Rossetti's nature, and Robert Buchanan's

attack on Rossetti and Swinburne in "The Fleshly School of Poetry" (1871)

changed him completely. In the summer of 1872 he suffered a mental breakdown,

complete with hallucinations and accusing voices. He was taken to Scotland,

where he attempted suicide, but gradually recovered, and within a few months

was able to paint again. His health continued to deteriorate slowly (he was

still taking chloral), but did not much interfere with his work. He died of

kidney failure on April 9, 1882”. [1]

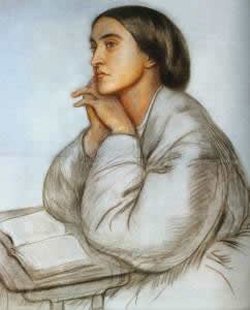

“Christina

Georgina Rossetti, one of the most important women poets writing in

nineteen-century England was born in London and educated at home by her mother.

In the 1840s her family was stricken with severe financial difficulties due to

the deterioration of her father's physical and mental health. When she was 14,

Rossetti suffered a nervous breakdown which was followed by bouts of depression

and related illness. During this period she, her mother, and her sister became

seriously interested in the Anglo-Catholic movement that was part of the Church of England. This religious devotion played a major role in

Rossetti's personal life: in her late teens she became engaged to the painter James Collinson but this ended because he reverted to Catholicism; later she

became involved with the linguist Charles Cayley but did not marry him, also for religious reasons.

Rossetti began writing at age 7 but she was 31 before her

first work was published — Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862). The collection garnered

much critical praise and, according to Jan Marsh, "Elizabeth Barrett Browning's death two months later led to Rossetti being hailed as her natural

successor as 'female laureate'." The title poem from this book is

Rossetti's best known work and, although at first glance it may seem merely to

be a nursery rhyme about two sisters' misadventures with goblins, the poem is

multi-layered, challenging, and complex. Critics have interpreted the piece in

a variety of ways: seeing it as an allegory about temptation and salvation; a

commentary on Victorian gender roles and female agency; and a work about erotic desire and social

redemption. Some readers have noted its likeness to Coleridge's "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" given both poems' religious themes of temptation, sin and

redemption by vicarious suffering. Her Christmas poem "In the Bleak Midwinter" became widely known after her death when set as a Christmas carol

by Gustav

Holst as well as by other composers.

Rossetti continued to write and publish for the rest of her life

although she focused primarily on devotional writing and children's poetry. She

maintained a large circle of friends and for ten years volunteered at a home

for prostitutes. She was ambivalent about women's

suffrage but many scholars have

identified feminist themes in her poetry. Furthermore, as Marsh notes, "she was opposed

to war, slavery (in the American South), cruelty to animals (in the prevalent practice of

animal experimentation), the exploitation of girls in

under-age prostitution and all forms of military aggression."

In 1893 Rossetti developed cancer and Graves' disease then died the following year

due to the cancer on December 29, 1894”. [2]

As we have seen, both authors had to

be with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Dante was one of its founders and

Christina was a “member” (her work shared the characteristics of the rest of

Raphalites but she never was an official member). I think it is important to

know something about this brotherhood, its origin, ideals, members, stages, and

the new features they brought to literature and art.

“The term Pre-Raphaelite, which refers to both art and

literature, is confusing because there were essentially two different and

almost opposed movements, the second of which grew out of the first. The term

itself originated in relation to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an influential

group of mid-nineteenth-century avante garde painters associated with Ruskin who had great

effect upon British, American, and European art. Those poets who had some

connection with these artists and whose work presumably shares the

characteristics of their art include Dante

Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti, George

Meredith, William Morris, and Algernon Charles Swinburne.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) was founded in 1849 by William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), D.G. Rossetti, John Everett Millais

(1829-1896), William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Thomas Woolner, and F. G. Stephens to revitalize the arts”.[3]

They were the reference in British

art and literature in the 2nd period of the 19th century.

They created the brotherhood to revitalize British art. Although they did not

published a manifesto, their main ideals could come from Ruskin’s praise of the

artist as prophet. Their main “new-revolutionaries” artistic ideals were:

- Testing and defying all conventions of art; for example,

if the Royal Academy schools taught art students to compose paintings with

(a) pyramidal groupings of figures, (b) one major source of light at one

side matched by a lesser one on the opposite, and (c) an emphasis on rich

shadow and tone at the expense of color, the PRB with brilliant perversity

painted bright-colored, evenly lit pictures that appeared almost flat.

- The PRB also emphasized precise, almost photographic

representation of even humble objects, particularly those in the immediate

foreground (which were traditionally left blurred or in shade) --thus

violating conventional views of both proper style and subject.

- Following Ruskin, they attempted to transform the

resultant hard-edge realism (created by 1 and 2) by combining it with typological symbolism. At their most successful,

the PRB produced a magic or symbolic realism, often using devices found in

the poetry of Tennyson and Browning.

- Believing that the arts were closely allied, the PRB

encouraged artists and writers to practice each other's art, though only

D.G. Rossetti did so with particular success.

- Looking for new subjects, they drew upon Shakespeare,

Keats, and Tennyson. [3]

This first stage of Pre-Raphaelitism had more influence on

visual arts, it was the second stage of the pre-Raphaelitism, headed by Dante

Gabriel, the one which was much more important on poetry and in literature in

general:

“The second form of Pre-Raphaelitism, which grows out of the first under

the direction of D.G. Rossetti, is Aesthetic

Pre-Raphaelitism, and it in turn produced the Arts

and Crafts Movement, modern functional design, and the Aesthetes and Decadents. Rossetti and

his follower Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) emphasized themes of eroticized

medievalism (or medievalized eroticism) and pictorial techniques that produced

moody atmosphere. This form of Pre-Raphaelitism has most relevance to poetry;

for although the earlier combination of a realistic style with elaborate

symbolism appears in a few poems, particularly those of the Rossettis, this

second stage finally had the most influence upon literature. All the poets

associated with Pre-Raphaelitism draw upon the poetic continuum that descends

from Spenser through Keats and Tennyson — one that

emphasizes lush vowel sounds, sensuous description, and subjective

psychological states.

Pre-Raphaelitism

in poetry had major influence upon the writers of the Decadence as well as upon

Gerard Manley Hopkins and W.B. Yeats,

both of whom were also influenced by Ruskin and visual Pre-Raphaelitism”.[3]

The realistic

style and the elaborate symbolism do not appear in a lot of poems but in the

Rossettis works. The main characteristics of the “new literature” were the lush

vowel sounds, sensuous description( so important in D.G. Rossetti’s work(the

medievalized eroticism)) and subjectivity.

Now that we know the lives of the Rossettis and their

artistic inner circle, we are going to see an example of their work: “The

Blessed Damozel” by Dante Gabriel and “Song (When I am Dead)” by

Christina. Both poems have a lot in common and obviously many differences.

Let’s analyze them.

“The Blessed Damozel” is probably the

most important single work by Dante Rossetti. It was started in 1846 and was

revised and extended(the complete Double Work) until 1881. As a Double Work, it

combines text and image. We are going to analyze it as a whole.

The poem is a ballad, which meter is a sestet, iambic

that alternates trimester and tetrameter. The rhyme is a4-b3-c4-b3-d4-b3.

Dante started the written part in 1847 and the

pictorial work in 1871 and he finished in 1881. “As a “double work of art” it is unusual in DGR's corpus because the

poems preceded the pictorial treatments”.[4]

Usually, the works by Rossetti the paintings were done

first and the poems were written from the image. The picture work as an

inspiration. Not in this case.

The subject of the poem is the

“Dantean” topic of the man who dreams/thinks about his beloved woman, who

is dead. She looking at him from the paradise, admiring

him.

“In "The Blessed Damozel" Dante Gabriel Rossetti illustrates the gap

between heaven and earth. The damozel looks down from Heaven, yearning for her

lover that remains on earth. Through imagery Rossetti connects the heavenly

damozel to things of the earth, symbolizing her longing but emphasizing the

distance between the lovers. She stands on God's rampart, which is

So high, that looking downward thence

She scarce could see the sun.

It lies in Heaven, across the flood

Of ether, as a bridge.

Beneath, the tides of day and night

With flame and darkness ridge

The void, as low as where this earth

Spins like a fretful midge.”[5]

The man is on earth and he is thinking about her woman,

he maybe is dreaming or having a vision

where he admires his love: “The

foundational Rossettian subject of the emparadised woman is in this case

imagined as dreaming downward, as it were, to her lover who remains alive in

the world. This imagination of the damozel is here structured as the

“dream-vision” of the lover himself”.[4]

The poem has 144 verses, but, the most famous are the 24 first, that is,

the first four stanzas. They are included on the base of the frame, and tell us

the story about how they were separated by death. Here, the Damozel asks why

has she been separated from her love and why can she stay with him now. He is

seen as a prisoner on earth. Maybe he would prefer to die and meet with his

love again in heaven.

“The

first four stanzas of "The Blessed Damozel" are also written on the

base of the frame, which Rossetti designed."The Blessed Damozel"

tells the beautiful yet tragic tale of how two lovers are separated by the

death of the Damozel and how she wishes to enter paradise, but only with her

beloved by her side. Rossetti takes this theme of separated lovers that are to

be rejoined in heaven from Dante's Vita Nuova, a continual source of

inspiration. Rossetti divides the painting into two sections with a principal

canvas on top and a narrower predella canvas beneath — a style reminiscent of

Italian Renaissance altarpieces. The upper part shows the Damozel in Heaven,

leaning over the golden bar or "barrier," surrounded by angels and

flowers. She holds three lilies in her hands and stars encircle her flowing red

hair. She gazes longingly down towards her beloved, depicted on Earth with

grass and trees, in the lower predella. His hands are clasped above his head,

emphasizing his plea and his state as a prisoner on Earth. The painting

directly corresponds to the first verse of the poem”.[6]

The poem is divided in three points of view or levels:

The Damozel’s one, from Heaven; the lover’s, from his

dream vision and again the lover’s, but this time from his conscious

reflection, that is, from his thoughts. In the last case, the thoughts are

quoted by parentheses. Ex:

Had counted as ten years.

(To one, it is ten years of years.

. . . Yet now, and in this place,

Surely she leaned o'er me — her hair

Fell all about my face. . . .

Nothing: the autumn-fall of leaves.

The whole year sets apace.)[…]

Her voice was like the voice of the stars

Had when they sang together.

(Ah sweet! Even now, in that bird's

song,

Strove not her accents there,

Fain to be hearkened? When those bells

Possessed the mid-day air,

Strove not her steps to reach my side

Down all the echoing stair?)

'I wish that he were come to me,[…]

Her eyes prayed, and she smil'd.

(I saw her smile.) But soon their

path

Was vague in distant spheres:

And then she cast her arms along

The golden barriers,

And laid her face between her hands,

And wept. (I heard her tears.)[7]

“The poem

operates at three levels, or from three points of vantage: the damozel's (from

heaven), the lover's (from his dream-vision), and the lover's (from his

conscious reflection). The last of these is signalled in the text by

parentheses, which enclose the lover's thoughts on the vision of his desire.

The pictures of

course have their own integral meanings, but they should also be seen as

“readings” of their precursive texts. The composite body of texts and images

makes up a closely integrated network of materials; it is a network, moreover,

that stands as an index of DGR's essential artistic ideals and practises”.[4]

Although the author makes a wall which separates

clearly earth from heaven and of course, the lovers, as we read the poem we

notice the author puts the lovers so near. She is described not as having “an ethereal beauty but as an earthly beauty”.

She is so earthly.

That is why he

remembers her as she was when died, she is in heaven but he has her in his

heart, and his heart is on earth. So she is in some way, on earth.

At the same time the author locates the heaven so far

from the earth, Dante uses the water imagery (which are so earthly) to connect

both worlds.

“Though

distanced so far from the earth, her hair is "yellow like ripe corn."

Rather than declare her ethereal beauty, Rossetti depicts the damozel's

appearance through earthly detail. She may be far from her lover and fixed in

Heaven, but her appearance and her gaze, like her heart, is grounded with her

beloved on earth. Even Rossetti's description of the space between the two

lovers is an attempt to unite Heaven and earth. He calls the ether a

"flood" and the rampart above the ether a "bridge," both

images of inherently earthly qualities — water and the manmade construction

that crosses it. The passing of day and night belows her are "tides"

tinged by flame and darkness. The earth is so far from heaven it looks

"like a fretful midge" — small, agitated, and a sharp contrast to the

peaceful stillness of Heaven”.[5]

The water imagery is used to connect them, but also to

separate them, it is ironic. The deep of

her eyes reflects the space there is between both. “This

picture of the space separating the lovers mirrors Rossetti's description of

the damozel's eyes. Just as the ether is a flood, her eyes "were deeper

than the depth of waters stilled at even." The damozel sees only the

distance from her beloved, and through most of the stanzas, she prays for and

imagines their union together, rather than immersing herself in Heaven. Heaven

is fixed, while the earth spins fretfully, and in an ironic twist, the

damozel's gaze is fixed upon the earth. Rossetti creates a poignant sense of

her longing by depicting her gaze and her heavenly position through earthly

images, and in effect, he gives the reader a glimpse of the heavens from the

damozel's unreachable position”.[5]

It is so important the Dantean inspiration that Rossetti uses in this Double

Work. Its parallelism with Dante and Beatrice is clear. The poem centers in The Vita Nuova.

The parallelism is obvious, Beatrice (the blessed Damozel) is the

emparadised lover and Dante (lover) is

on earth, he can reach her. “The

principal source is generally Dantean, and especially the material that centers

in the Vita Nuova . The most

revealing passage is probably the famous canzone “Donne ch'avete intelletto

d'amore” which comes in section XIX.

The canzone treats the position that Beatrice, the emparadised beloved, has in

relation both to mortal creatures, including Dante, and the beings of heaven,

including God”[4].

The other parallelism we can relate this poem to is an autobiographical

one. As we have read in the biography, he married to Elizabeth Siddal in 1860

and she died in 1862. He included or transported her image to the poem’s

Damozel.

“Begun as a stil novist exercise, the poem later

assumed a distinct autobiographical dimension as the figure of the damozel

opened itself to parallels with Elizabeth Siddal whom he met in 1849 and

married in 1860. Her death in February 1862 translated her to the heaven

figured in Rossetti's poem. Devoted as he was to her, or at any rate to his

image of her, Rossetti became haunted by her ghostly presence—a haunting all

the more powerful because of Rossetti's remorse over his infidelities to Siddal

before and during their marriage”.[4]

Finally I would like to praise this poem as one of the most important of

the Victorian Era, because of its wonderful combination between a beautiful

text and a splendid fogg oil painting that makes this piece of work a reference

inside the Victorian Era and in the British art, as a representation of the

revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood artists.

Now, we will analyse the poem “Song”, by Christina Rossetti and will

look for the connection with her brother’s work.

“Many such painterly and literary

works clearly embody male vantage points. Many such poems are actually spoken

by male characters throughout (as in "The Blessed Damozel" and "Porphyria's Lover"), or end with male voices

(as in "The Lady of Shalott"). Christina Rossetti offers the rare

example of a Victorian woman poet who talks back. She does so in several poems

the nature of whose speakers suggest how difficult, almost impossible, that act

is: her female speakers are dead and their voices come from beyond the

grave”.[8]

As G.P. Landow says, Christina Rossetti was a unique poet and her works

are unique. In “Song”, Rossetti creates

a new character, “a dead woman who talks

back”, a woman who speaks from the grave and who is going to be listened,

heard for the first time. The prototypic male point of view of these poems is

now changed to the side of the women, that dead women who is admired by the man

but who has never had the chance to speak.

“Christina Rossetti is one of the

few poets, male or female, who creates such unusual poetic

characters[…]Rossetti's dead speakers concentrate more narrowly upon offering a

woman's view of male conceptions of romantic love and loss. "After

Death," which we may pair with "Song," another poem dating from

around 1862, presents what seems to be a conventional view of pure, sacrificial

womanly love. In this brief poem, the speaker, whom we gradually realize is

dead, seems to embody the standard self-pitying adolescent fantasy expressed in

the words, "they'll miss me when I'm gone (sob)": Here a man whom the

female speaker loves but who did not see her worthy of love while she was alive

at least notices her now she's dead”.[8]

The female speaker of the poem “comes” to say all that she could not say

when she was alive. She suffered a lot by her feelings of loss for her lover, she feels as if never had

been really loved. Now she is dead, she does not seem sad or hurt, she seems to

be in peace. She does not want to remembered as in the typical Victorian poems,

as a beautiful and forever beloved woman. She doesn’t need this. That was so

radical and so new in the Victorian Era. She does not need to be loved, to be

praised now she is dead, she want to be loved when she was alive, when she

could share her life with her love:

“Sentimentalized depictions of the

tragic death of women occupied many PRB poems and paintings. The

familiar stories of Mariana and The Lady of Shalott make women into objects,

manipulated and toyed with. They place women at the mercy of the men in their

lives. These works come from a male vantage point. Christina Rossetti provides

a unique rebuttal to these works in her poem, "Song". Here, Rossetti

voices the inner thoughts of a dead Victorian woman. As though in response to

her brother's poem, "The Blessed Damozel" (text) in which a woman, tortured by

her feelings of loss for her lover, stirs in heaven, Christina Rossetti's woman

in "Song" feels no pain or loss, but rather only peace. Christina

Rossetti paints a picture of heaven devoid of human earthly desire, in fact

characterized by ambivalence. Her woman does not pine for her lover; she states

that she might actually forget him altogether in time. Rossetti's woman, not at

the mercy of her lover, finds herself free of desire for him. She has moved

onto another part of her life. Although her poems centred on the depiction of

love, Rossetti's love translates from earthly passion to a peaceful, higher

spirituality and comfort upon death. "Song", exposes the inadequacy

of earthly love when compared with the peace and fulfilment experienced by the

woman upon death”. [9]

This fact, this change in the vantage point takes to pieces the male

tradition in this elegiac poems, where the women were more an object to be

admire, an inspiration than a person:

“The note of complete

indifference on which Christina Rossetti ends this poem is particularly

shocking when seen in the context of male tradition. Rossetti’s speaker here does

not pine for her male partner to join her; indeed, she suggests that she has

increasing difficulty in remembering him at all — and that's not a matter of

serious concern or regret. The poet's wordplay increases the effect, for much

depends on "haply," which might mean "possibly" or even

serve as a poetic version of "happily." The first meaning of the word

is harsh enough because it conveys the speaker's increasing indifference, the

second her pleasure in such forgetfulness. Either way a new female voice

reconfigures the poetic tradition”.[8]

shall

not see the shadows,

I shall not feel the rain;

I shall not hear the nightingale

Sing on, as if in pain:

And dreaming through the twilight

That doth not rise nor set,

Haply I may remember,

And haply may forget.

Here, Christina changes the role of woman and seems to locate herself

against her brother (his Italian male poetic tradition and role of women), she

changes these common use of objectified women:

“In "Song," Christina Rossetti

is both working through and against the Italian male poetic tradition so

important to her brother. The female speaker in "Song" does what

Dante Gabriel's idealized and objectified woman in "The Blessed Damozel" is never able to do. As George P.

Landow discusses in "The Dead Woman Talks

Back: Christina

Rossetti's Ironic Intonation of the Dead Fair Maiden," the dead woman

literally addresses her beloved from the grave and for once is allowed to

"talk back" and be heard. The obvious impossibility of this situation

occurring under normal circumstances suggests the extent to which the female

voice was suppressed in society. As Landow points out, the speaker's

unwillingness to let her beloved grieve over her absence is reminiscent of

Dante Gabriel's notion of the selfless female”[10]:

When I am dead, my

dearest,

Sing no sad songs for me. . .

And if thou wilt, remember,

And if thou wilt, forget.

I think the aspect that stands out in this poem is the sensation of indifference that the speaker seems to

show toward her lover:

“What initially appears to be a

typical self-sacrificing female speaker turns out to be a complete rejection of

this Victorian stereotype. In contrast to Dante Gabriel's poem "The

Blessed Damozel" in which the male speaker imagines his dead beloved

desperately longing for him in heaven, the female speaker in Christina

Rossetti's "Song" has an attitude of total indifference to the male

figure”.

The point of view focused in a female speaker, was used in “Song” and

other poems as “After Death”. This female speaker shows the indifference we

have talked about, the peace she feels and how she moves away from her lover.

Also why she is now so indifferent. She is so indifferent because she suffered a lot by her feelings of loss for her lover, as we see in “After

Death”:

AFTER DEATH

The curtains were half drawn; the floor was swept

And strewn with rushes; rosemary and may

Lay thick upon the bed on which I lay,

Where, through the lattice, ivy-shadows crept.

He leaned above me, thinking that I slept

And could not hear him; but I heard him say,

"Poor child, poor child"; and as he turned away

Came a deep silence, and I knew he wept.

He did not touch the shroud, or raise

the fold

That hid my face, or take my hand in his,

Or ruffle the smooth pillows for my head.

He did not love me living; but once dead

He pitied me; and very sweet it is

To know he still is warm though I am cold.

Christina Rossetti was not only one of the most important female poets

of the British history but also a reference for all the writers in Britain, as

she brought new features and a new way to use the classic Italian male poetic

tradition which was the reference for the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and of

course for his brother. By writing poems as “Song” or “After Death” she changed

the stereotypes of Victorian poetry and

contributed together with her brother and other authors and members of the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to the

creation of a modern view in arts.

Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti were two references in the

Victorian Era, they helped the evolution of poetry and art in general in

Britain. Dante leaded the Pre-Raphaelites, created wonderful Double Works which

changed the way of doing poetry. Christina Rossetti was the most important poet

woman since Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and was of the most important of all

time. She was a reference not only for poet women but also for male authors.

They are two of the most important Victorian artists by far.

NOTES:

[1] from Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Biography; Victorian Web,1988http://victorianweb.org/authors/dgr/dgrseti13.html

[2]from Wikipedia, Christina Rossetti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christina_Rossetti

[3]from Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction, by George P. Landau, Victorian

Web http://victorianweb.org/painting/prb/1.html

[4] from The Blessed Damozel, DG Rossetti, General description, www.Rossetiarchive.org) http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/1-1847.s244.raw.html

[5] from “Parallel Imagery in The Blessed

Damozel”, Adrienne Johnson’05 English History of Art. Pre-Raphaelites, Aesthetes, and Decadents, Brown University, 2004. Victorian Web. http://victorianweb.org/authors/dgr/johnson5.htm

[6] from The Spiritual Depths of the Feminine Soul in Rossetti's

"The Blessed Damozel". Hae-in Kim, English/History of Art 151, Pre-Raphaelites, Aesthetes, and Decadents, Brown University, 2004. Victorian Web. http://victorianweb.org/authors/dgr/hikim5.html

[7] “The

Blessed Damozel”1847-1881, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, from Representative

Poetry Online. http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/1763.html

[8] from The Dead

Woman Talks Back: Christina Rossetti's Ironic Intonation of the Dead Fair

Maiden George P. Landow, Shaw

Professor of English and Digital Culture, National University of Singapore. http://victorianweb.org/authors/crossetti/gpl1.html

[9] from A Woman's

Voice in Rossetti's "Song". Meaghan Kelly '05.5, English/History of

Art 151, Pre-Raphaelites, Aesthetes, and Decadents, Brown University, 2004. Victorian Web. http://victorianweb.org/authors/crossetti/kelly6.html

[10] from Representations of the Female Voice in Victorian Poetry.

Breanna Byecroft '05, English 151, Brown University, Autumn 2003. http://victorianweb.org/authors/ebb/byecroft14.html#damozel

[11] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Christina_Rossetti_2.jpg

[12] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dante_Gabriel_Rossetti

[13] http://www.wordreference.com