Class

Notes

Here

you will find the daily notes about the things we talk about in class ordered

by date.

17-2-09

Indo-European

Different

languages can be systematically compared, and depending on the number and kind

of similarities, the relationship between them can be established.

Traced

to a common attested, reconstructed or allegedly reconstructable

(proto-language i.e. en which case they are “cognate”) or they have no

attested, reconstructed or allegedly reconstructable common ancestor.

A.

Genetic Tree Theory: (August Schleicher 1861-2): the

origin of individual languages is caused by “branching off” from older

languages. Differentiation into daughter languages is abrupt and clear cut.

B.

Wave theory: (Hugo Schuchardt: 1868). Language change

starts in restricted contexts within a certain community. The change spreads to

further contexts and social groups until it is realized in all contexts and

with all speakers.

Genetic

relationships between languages, according to the Genetic Tree Theory, exist if

there’s a clear linguistic evidence of a close relationship between those

languages:

-

ancestor language: it is the parent language (i.e.

Latin)

-

daughter language (as Italian or Spanish would be in

relation to Latin)

-

sister languages (as Italian and Spanish would be

between them)

A

group of genetically related languages:

-

language family in the narrow sense, or a branch if the group is composed only

of parent languages and its daughters.

-

language family in the broad sense, when the group is formed by related

languages.

Reconstruction

of non-existent languages:

-

DEF: procedure for determining older non-recorded or

not very attested stages of language based on.

-

our knowledge of possible types of change (e.g. a

possible sound change).

Phonetically

motivated changes: simplicity in the articulation (e.g haevtu > haeftu).

Phonologically

motivated changes: maximal distinctiveness of speech sounds.

Synchronic

linguistic data (e.g. sounds in today’s languages).

Two

types of reconstruction depending on the type of synchronic linguistic data.

Based on:

-

language-internal reconstruction: if historical forms

are reconstructed on the basis of systematic relationships within a single

language (e.g. ablaut in Indo-European based on Greek).

-

Language-external (comparative) reconstruction: if

historical forms are reconstructed on systematic relationships between

different presumably genetically related languages.

Pater

– Vater – Father

Pod

– Fuss – Fast

(reconstruction

by comparing. We don’t know it in OE but we do it by comparing for example

Latin, German).

19-2-09

Accidental similarities:

●

the Greek verb “to breathe”, “blow” has the root pneu-. In Klamath of Oregon

the root for the same verb is pniw-, but these languages aren’t remotely

related.

●

in the languages of most countries, the cuckoo has a name derived from the

noise it makes (honomatopoeia).

●

we try to reconstruct the parent form of forms used in contemporary Romance

languages to denote “father”. We apply external reconstruction, we collect

words from different potentially cognate languages

Padre (Italian)

Pare (Catalan)

Père (French)

The

following processes may happen universally in the evolution of languages:

●

Weakening (lenisization): which couldn’t result in the change [t] > [d] >

[Ø] in the derivation of the above forms from their common parent form (in

agreement with the trend towards simplicity in articulatory effort).

Example

of weakening: /daðo/ (verbo dar) >

/dao/

●

Metathesis: e.g. [er] > [re] when deriving the forms in the daughter

languages.

bren

> burn

hros

> horse

●

Vowel harmony: it could cause the change of the putative vowel [a] in the first

syllable into [e] under the influence of the vowel [e] of the second syllable,

resulting in the present French form. (One vowel influences another).

foot,

feet (foti: it was the original plural).

3-03-09

I.E. and the Indo-Europeans

-

Who were the Indo-Europeans? Where did they live?

Where did they migrate?

●

A now extinct language, ancestor of a linguistic family of most of the European

languages, past and present and those found in a vast area from

●

The English orientalist and jurist Sir William Jones (1746-94) discovered the

link between Sanskrit, Latin and Greek. He discovered similarities that could

not be accidental.

English

English

belongs to the West Germanic branch. The 85% of the English vocabulary has been

lost and English has borrowed from Germanic and Romance neighbours and from

Latin and Greek the inherited vocabulary. A small proportion of the total

remains the genuine core of the language.

●

all of the 100 words most frequent in the Corpus (collection of words in

contexts) of Present Day American English (Brown Corpus) are native, and of the

second 100, 83 are native.

●

over the 50% of the English vocabulary comes from I.E., inherited or borrowed

(function words, modal verbs).

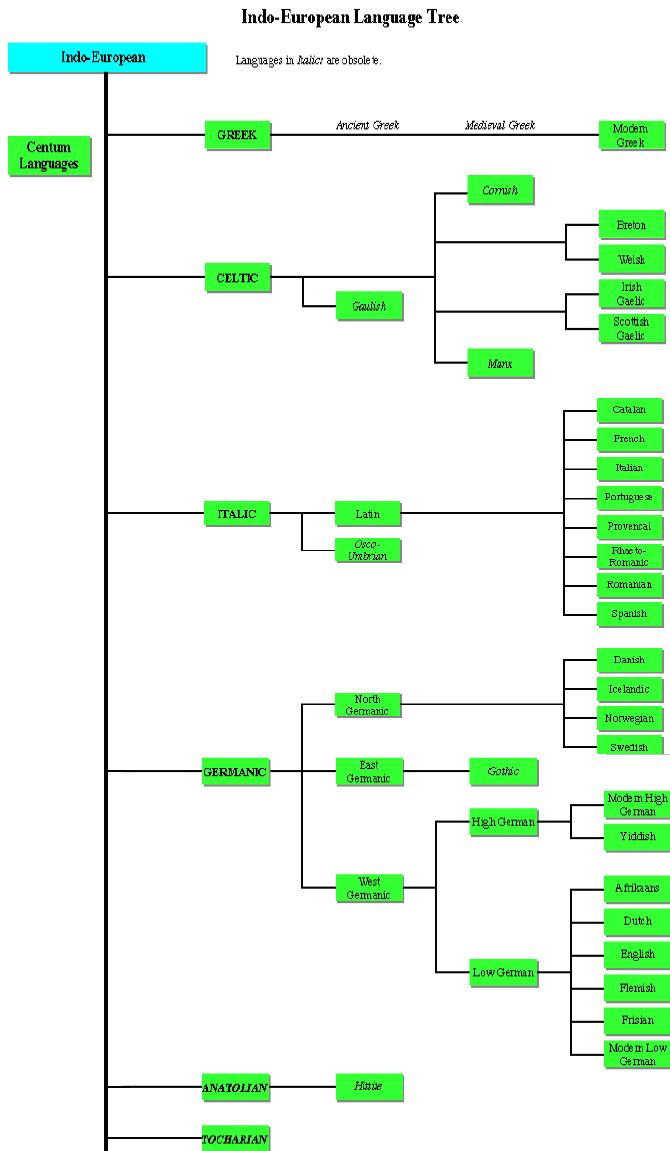

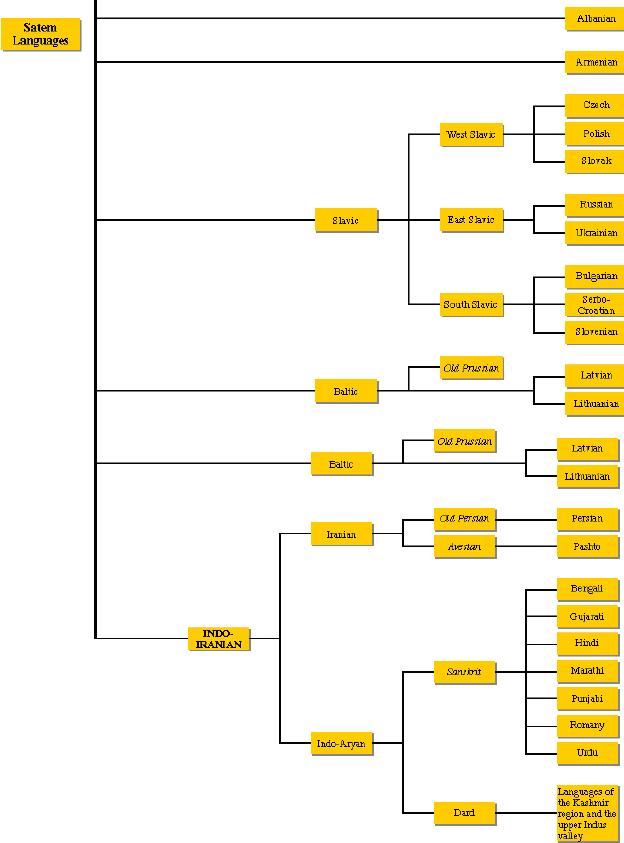

Centum languages:

Satem languages:

From the Romans to the

●

Celts and Romans:

-

the first inhabitants of

-

then the Celts occupied France (Gaul), the North of Italy, Netherlands, Spain,

North-West of Germany, Great Britain and Ireland in Western Europe history.

●

Celts:

-

there seems to have been no code-mixing between Celtic languages and

Anglo-Saxon.

-

this might explain the lack of Celtic influence in the nowadays English.

-

no new words were needed as Continental

Europe and

●

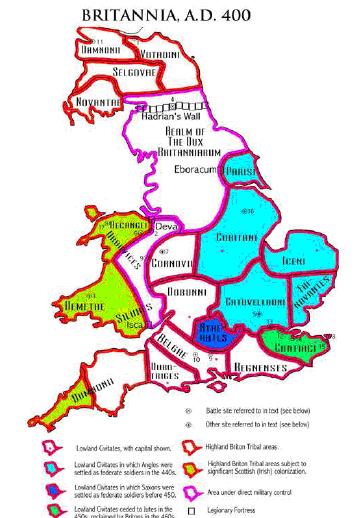

Britannia and Roman domination

-

Julius Cesar invaded in 55 and 54 B.C. intending to secure an area in the

South-East of

-

-

no attempt to conquer the whole island or

-

large areas in

10-03-09

Traces of Roman influence

Ø

Place-names: -cester or

Ø

Ø

De Excidio Britanniae

Ø

407/410 A.D. the Roan legions left Britannia to defend

the empire from Germanic raids.

Ø

Romanised Britons left alone to face the attacks by

the Picti (

Ø

Eventually, the inhabitants of

Ø

Germanic mercenaries landed in

Adventus Anglorum

◦ Jutes arrived in

◦ Angles (from: Angulum terrae,

◦ Saxons (called after the sax, a kind of axe) settled

in Essex, Wessa, Middlesex and

◦ The most important

◦ The seven main kingdoms competing for supremacy formed

the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy:

Map of Anglo-Saxon

Heptarchy:

●

● In the 7th and 8th

centuries, the supremacy passed on to

●

●

At the end of the 8th century

Celts and Anglo-Saxons

○

Britons and Anglo-Saxons cohabited peacefully at first, but Celtic languages

and customs had very little influence on the Anglo-Saxons.

○

Celtic Britons resisted Saxon invaders. King Arthur –probably a Romanized

Celtic chieftain- fought briefly against the invaders, but domination was

inevitable.

○

About 557 most of

Latin influence

○

The Germanic invaders didn’t adopt Latin because:

-

there was no coexistence with Latin speaking Britons

-

decadence of Roman civilization

-

Germanic tribes invaded Britannia and had had little contact with the

○

Latinization: Pope Gregory sent

9th/11th century: Viking

Invasions

Ø

Ø

From then on pirates coming from

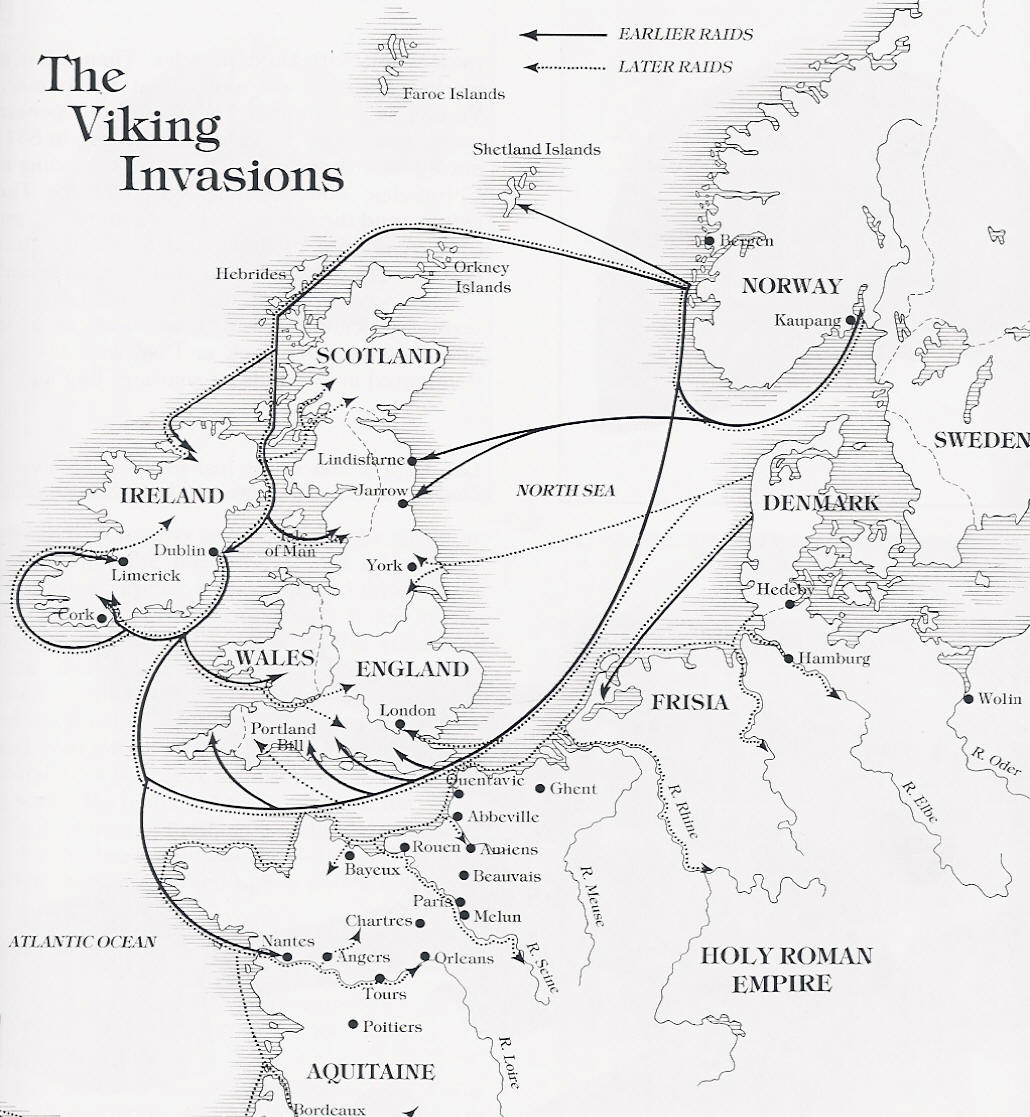

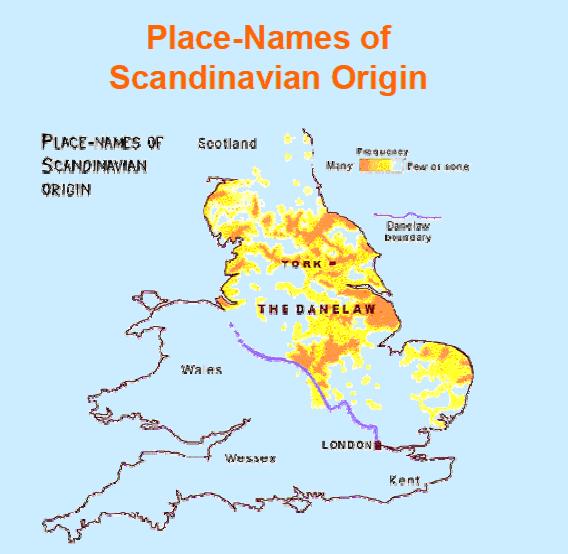

Map of the Viking

Invasions:

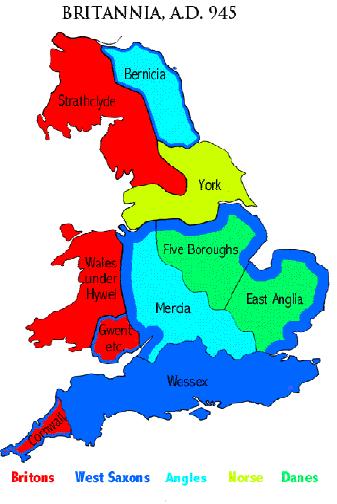

Map of Britannia’s

dialects in

Ø

The Viking invaders were defeated by Alfred the Great

in the battle of Edington in 878.

Ø

The subsequent peace treaty led to the division of the

territory into two:

Ø

By 970, the Danelaw (parts of north Lancashire,

Westmoreland and

Map: The Danelaw:

Treaty of Wedmore

The Norman Conquest

Ø

When Edward the Confessor died, the Anglo-Saxon

noblemen elected Harold, son of Godwin, as the new king.

Ø

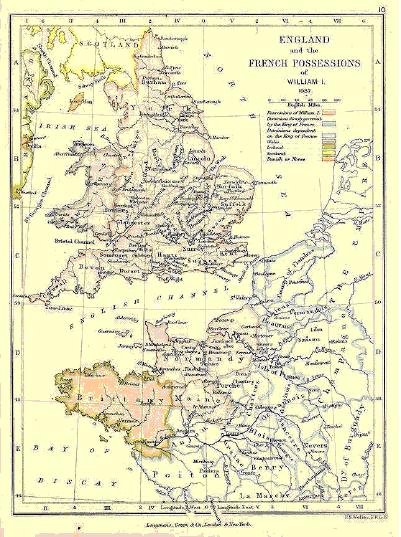

William of Normandy, second cousin of king Edward,

thought that he was the legal king of

12-03-09

Ø

William of Normandy invaded

Ø

Originally Norsemen, they came from the French region

of

Ø

The new king imported the principle of the feudal

system: the state as a hierarchy where every member was directly responsible

for the person above him.

Ø

William brought with him Norman barons and clerics and

replaced the native nobility in the state and Church.

Ø

1086 only two of the greater landlords and only two

bishops were Saxon.

Linguistic situation until the 13th century

Ø

language of Church and court was Norman, French and

Latin.

Ø

King, greater feudal landlords, higher clergy: French,

Latin.

Ø

Lesser landlords and clergy: bilingual.

Ø

Most people of Saxons descent spoke only English.

Ø

English was disdained by the upper classes; it was no

longer written. Anglo-Saxon chronicles ended in 1155.

The rise of English

Ø

1204-1348: several events would seal the resurgence of

English over Norman French:

-

the Black Death: fewer workers meant that landlords

gave land to English-speaking tenants for rent.

-

The 100 Years War: gradual loss of dominions of the continent.

-

The creation of cities and birth of middle classes

(the lower ones became middle, and they spoke English).

-

The Parisian dialect became more fashionable than

Norman French, and was used in Universities and other centres of culture.

26-03-09

Old English

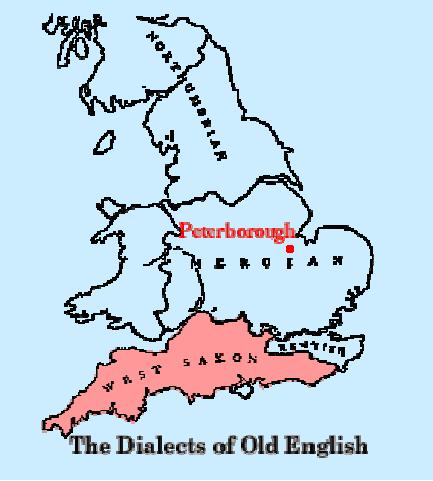

• The Old English we

generally study is a kind of standard, elaborated on the basis of

one of the dialects

spoken at that time (West Saxon) plus the addition of grammatical,

syntactic and lexical

features from other dialects.

• Different dialects

spoken depended on where each Germanic tribe settled. (See Heptarchy map).

Old English Periods

• Pre-Old English

(449/450-700), paucity of written records.

• Early Old English

(700-900), use of a literary dialect (West Saxon). Made important by King

Alfred and his collaborators.

• Old English proper

(900-1150).

Linguistic Situation in OE Period

• a. Anglian: spoken

north of river

a.1. Northumbrian:

north of river.

a.2. Mercian:

between Humber and

• b. Kentish: the

south-east of

• c. West-Saxon:

south-west of

Changes from Old English to Middle

English

• Morphosyntactic Change

• Syntactic Change

• Lexical Change

Morphosyntactic Change

• Gender in the article system

disappears.

OE ME

MASCULINE se wulf þe wulf

FEMENINE seo giefu þe gift

NEUTER þæt land þe land

• Natural gender takes over in

the pronoun system: it to refer to most objects and he, she to

males and females and some objects such as ship.

• Simplification of

the cases in the article system

OE ME

Masculine All genders

Nom se þe

Acc þone þe

Dat þǽm þe

Gen þæs þe

• Simplification of noun endings

Singular Plural

OE ME OE ME

Nominative stān

stone stānas stones

Accusative stān

stone stānas stones

Genitive stānes

stone’s stanum stones’

Dative stāne

stone stāna stones

• Plural with s spreads to most nouns

Sing Plural Sing Plural

MASC. stan stanas

→ stone stones

FEM. giefu giefa

→ gift gifts

NEUT. ship shipu

→ ship ships

bok bec → book books

BUT

man men → man men

• Simplification of adjective endings

OE ME

Nom. se wilda wulf

te wild wulf

Acc. tone wildan wulf

te wild wulf

Gen. tas wildan wulfes te wild wulf

Dat. Tǽm wildan wulfe te wild wulf

Nom. ta wildan wulfas te wild wulfes

Acc. ta wildan wulfas te wild wulfes

Gen. tǽra wildra wulfa te wild wulfes

Dat. tǽm wildum wulfum te wild wulfes

Syntax From OE to ME

• Word order became more important with the loss of declensions.

• Scandinavian phrasal verbs: gyfen up, faren mid, leten up, tacen

to.

• Use of Scandinavian verbal operator get.

• Use of operator do:

Wryteth ye this with your owne hande?

Dyd ye wryte this with

your owne hande?

Celtic substratum

• Very few words of Celtic origin are found in Modern English:

• Rivers: Avon, Clyde, Dee, Don, Forth,

Severn,

• Axminster, Caerleon-on-Usk, Exmouth, Uxbridge from

the word for water.

• The word whisky/whiskey also comes from a compound of this

word: uisge beatha =

water of life

• Cities:

• Landscape words: ben, cairn, corrie, crag,

crannog, cromlech, dolmen, glen, loch,

menhir, strath, tor:

• First Names: Alan, Donald, Duncan, Eileen,

Fiona, Gavin, Ronald, Sheila

• Other words: badger -brock - tejón; peat - turba; bucket – cubo; dun = “dark coloured”, binn = “basket”

• Some of the Celtic words that entered English come from Latin. These

words

were borrowed during the Roman occupation of

• car, carry, carriage, chariot, charioteer,

carpenter, carpentry, lance, and lancer.

Latin Influence: Period of Continental Borrowing from Latin 1st to 5th

centuries A.D.

• Around 50 words through Germanic contact with

Latin influence: (from

Roman occupation of

Very little influence

during this period. Place names: ceaster (castra = “walled encampment'), for example: Dorchester,

Latin influence: Period of the Christianizing of Britain

(7th to 10th centuries AD)

• abbot, alms, pope, priest, oyster, fig,

pine, cedar, sack, sock, etc.

• loan translations (native word formations in imitation of a Latin

model) se haliga gast, godspel

Scandinavian Influence

• Toponyms

Scale (dwelling) Scalby Beck

-by (village) Ormsby, Kirkby

-gill (ravine) Aisgill

-fell (hill) Cross Fell

-thorpe (farm) Priesthorpe

-slack (dell, valley) Garton Slack

-thwaite Micklethwaite

Scandinavian Influence

• egg for OE ey

• sister for swuster

• leg for shanks

• Word pairs: skiff-ship;

skirt-shirt

• OE words replaced by Scandinavian words:

• take-niman; cast-weorpan

• cut-ceorfan, die-steorfan (starve)

• Function Words

til

though

they, their, them

both

same

against

Linguistic Situation in ME Period

1100-1450/1500

• English co-existed

with Anglo-Norman and Latin.

• Latin was the

written language of the Church and many secular documents.

• After the Conquest a

certain amount of bilingualism in

Norman Influence

• In Early ME 91.5 %

of words had English origin; in later Middle English this figure had fallen to

78.8 %.

• The language of 5 or

10% of the population became the most substantial source of new words in

written ME.

• 13th c. Parisian

French superseded Anglo-Norman French.

Vocabulary

• Pre-Conquest French borrowings: prud, castel.

• Early Post-Conquest words.

natiuite, canceler, concilie, carite,

• Borrowings increased dramatically around the 13th century, not because

of structural gaps but because they were felt to be stylistically more

suitable.

Norman and French Word Pairs

• Wile (1154) guile

(1225)

• warrant(1225) guarantee

(1624)

• warden(1225) guardian

(1466)

• reward(1315) regard (1430)

Latin Borrowings in ME

• Words of common use.

aggregate, applaude, assimilate, etc.

• Words used in the church, administration, education. curate,

pulpit. legitimate; elect, convict. pedagogue, graduate, literate.

7-4-09

Caxton

and the printing press

Caxton (1415/22 – 1492). English merchant,

diplomat, writer and printer. He introduced the printing press to

Caxton’s Version of Higden’s

Polycronicon 1482

As it is knowen how

many maner peple ben in this llond ther ben also many langages and tongues.

Netheles walschmen and scottes that ben not medled with other nacions kepe

neygh yet theyr first langage and speche.

Also englysshmen

though they had fro the beygynnyng thre maner speches Southern northern and

myddle speche in the middel of the londe, as they come of thre maner of people

of

This appayryng

(impairing) of the langage cometh to two thynges/ One is by cause that children

that gon to scole lerne to speke first englysshe / & than ben

compellid to constrewe

her lessons in Frenssh and that have ben vsed syn the

Also gentilmens

childeren ben lerned and taught from theyr yongthe to speke frenssh. And

vplondyssh (rustic) men will counterfete and likene hem self to

gentilmen and arn besy

to speke frensshe for to be more sette by (be thought more of).

This maner was moche

vsed to fore the grete deth. Buth syth it is somdele chaunged For sir Johan

cornuayl a mayster of gramer chaunged the techyng in gramer scole and

construction of Frenssh in to englysshe. and more Scoolmaysters vse the same way

now in the yere of oure lord / M.iij/C.lx.v the /ix (1385) yere of kyng Rychard

the secund and leve all frenssh in scoles and vse all construction in englissh.

Also gentilmen have

moche lefte to teche theyr children to speke frenssh Hit semeth a grete wonder

that Englyssmen have so grete dyversyte in theyr owne langage in sowne and in

spekyng of it / whiche is all in one ylond. And the langage of Normandye is

comen oute of another lond / and hath one maner soune among al men that speketh

it in englond…

George Puttenham The Arte of English Poesie (1590)

Now also wheras I said

before that our old Saxon English for his many monosillables did not

naturally admit the vse of the ancient feete in our vulgar measures so aptly as

in those languages which stood most vpon polisillables, I sayd it in a

sort truly, but now I must recant and confesse that our Normane English which

hath growen since William the Conquerour doth admit any of the auncient

feete, by reason of the many polysillables euen to sixe and seauen in

one word, which we at this day vse in our most ordinarie language: and which

corruption hath bene occasioned chiefly by the peeuish affectation not of the

Normans themʃelves, but of clerks and scholers

or secretaries long since, who not content with the vsual Normane or Saxon

word, would conuert the very Latine and Greeke word into vulgar French, as to

say innumerable for innombrable, reuocable, irreuocable, irradiation,

depopulatio & such like, which are not naturall Normans nor yet French, but

altered Latines, and without any imitation at all: which therefore were long

time despised for inkehorne termes, and now be reputed the best & most

delicat of any other.

George Puttenham The

Arte of English Poesie (1590)

But after a ſpeach

is fully faſhioned to the common vnderstanding, & accepted by conſent

of a whole countrey & natiō, it is called a language, & receaueth

none allowed alteration, but by extraordinary occaſions by little &

little, as it were inſenſibly bringing in of many corruptiōs that

creepe along with the time: of all which matters, we haue more largely ſpoken

in our bookes of the originals and pedigree of the English tong. Then when I

say language, I meane the ſpeach wherein the Poet or maker writeth be it

Greek or Latine or as our case is the vulgar English, & when it is peculiar

vnto a countrey it is called the mother ſpeach of that people: the Greekes

terme it Idioma: so is ours at this day the Norman English. Before the

Conquest of the

This part in our maker

or Poet must be heedyly looked vnto, that it be naturall, pure, and the most vſuall

of all his countrey: and for the ſame purpoſe rather that which is ſpoken

in the kings Court, or in the good townes and Cities within the land, then in

the marches and frontiers, or in port townes, where ſtraungers haunt for

traffike ſake, or yet in Vniuerſities where Schollers vſe much

peeuiſh affectation of words out of the primatiue languages, or finally,

in any vplandiſh village or corner of a Realme, where is no reſort

but of poore ruſticall or vnciuill people: neither ſhall he follow

the ſpeach of a craftes man or carter, or other of the inferiour ſort,

though he be inhabitant or bred in the beſt town and Citie in this Realme,

for ſuch persons doe abuſe good ſpeaches by ſtrange accents

or ill ſhapen ſoundes, and falſe ortographie. But he ſhall

follow generally the better brought vp ſort, ſuch as the Greekes call

[charientes] men ciuill and graciouſly behauoured and bred. Our

maker therfore at these dayes ſhall not follow Piers plowman nor Gower

nor Lydgate nor yet Chaucer, for their language is now out of

vſe with vs: neither ſhall he take the termes of Northern-men, ſuch

as they vſe in dayly talke, whether they be noble men or gentlemen, or of

their beſt clarkes all is a matter: nor in effect any ſpeach vſed

beyond the riuer of Trent, though no man can deny but that theirs is the purer

English Saxon at this day, yet it is not ſo Courtly nor ſo currant as

our Southerne English is, no more is the far Weſterne mās speach: ye ſhall

therfore take the vſuall speach of the Court, and that of London and the ſhires

lying about London within lx. myles, and not much aboue. I ſay not this

but that in euery ſhyre of England there be gentlemen and others that ſpeake

but ſpecially write as good Southerne as we of Middlesex or Surrey do, but

not the common people of euery ſhire, to whom the gentlemen, and also

their learned clarkes do for the most part condeſcend, but herein we are

already ruled by th'English Dictionaries and other bookes written by learned

men, and therefore it needeth none other direction in that behalfe.

Richard

Verstegan A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence 1608

Since the tyme of Chucer,

more Latin & French, hath bin mingled with our toung than left out of

it, but of late we haue falne to ſuch borowing of woords from, Latin,

French, and other toungs, that it had bin beyond all ſtay and limit, which

albeit ſome of vs do lyke wel and think our toung thereby much bettred,

yet do ſtrangers therefore carry the farre leſſe opinion

thereof, some saying that it is of it self no language at all, but the ſcum

of many langauges, others that it is most barren and that wee are dayly faine

to borrow woords for it (as though it yet lacked making) out of other languages

to patche it vp withall, and that yf wee were put to repay our borrowed ſpeech

back again, to the langauges that may lay claim vnto it; wee ſhould bee

left litle better then dumb, or ſcarſly able to speak any thing that

should bee ſensible.

This is a thing that

eaſily may happen in ſo ſpatious a toung as this, it beeing ſpoken

in ſo many different countries and regions, when wee ſee that in ſome

ſeueral partes of England it ſelf, both the names of things

and pronountiations of woords are ſomwhat different, and that among the

countrey people that neuer borrow any woords out of the Lain or French, and o

fhtis different pronountiation one example in ſteed of many ſhall ſuffice,

as this: for pronouncing according as one would ſay in London, I would

eat more cheeſe of I had it/the northern main ſaith, Ay

ſud eat mare cheee gin ay hadet/and the westerne man ſaith: Chud

eat more cheeſe an chad it. Lo heer three different pronountiations in

our own countrey in one thing, &heerof many the lyke examples might be

alleaged.

Chaucer

Chaucer (1340 – 1400). Writer, philosopher,

diplomat and English poet. He legitimized English in art and contributed too

the English literature’s development. In 1418 he wrote Canterbury Tales.

It was the beginning of a standard.

The

birth of a literary standard

Continental verse forms based on metrics and

rhyme were replaced by the Anglo-Saxon alliterative line in Middle English

poetry.

Video

about Dr. Johnson, the beginnings of

Standard English and the rise of RP.

Until

the 18th century, there was virtually no formal guidance about the

proper spelling and pronunciation of English. The language was in such a state

of flux that writers like Jonathan Swift proposed an academy to regulate it.

It

was not until Samuel Johnson started work on his dictionary in this house that what

we know as Standard English began to emerge.

Before

Dr. Johnson, writers like Jonathan Swift warned that English was being

corrupted by change. Johnson scorned the idea of permanence in language. To

believe in that, he said, was to believe in the elixir of eternal life. Yet,

paradoxically, the work that was done in this house gave the language its first

stabilizing authority, and it’s an important milestone in the history of

English.

The

two volumes of Johnson’s dictionary linked spoken English to a printed

standard. Now, the educated middle class learnt to speak like the dictionary

and scorned the illiterate Cockneys, who did not. The dictionary’s 40.000

definitions provide the basis of Standard English and its influence has lasted

to this day. Dr. Johnson treated English very practically, as a living

language, with words having different shades in meaning. Some of his

definitions are still miracles of clarity. For example: “Heart: the muscle

which by its contraction and dilation, propels the blood through the course of

circulation. It is supposed, in popular language, to be the seat sometimes of

courage, sometimes of affection”. And some were famously idiosyncratic like:

“Oats: a grain which, in

After

Johnson, people would spell and pronounce words according to the dictionary.

By

Victorian times, accent and class were becoming synonymous. Speech, education

and advancement went together. To guarantee good English, and a good future,

parents would send their children away to school. The English public schools

took boys from all over the country and gave them a Standard English accent.

With the right accent, the educated middle-class became captains of industry,

army and navy officers, imperial civil servants, lawyers, politicians, and even

teachers who would pass their accents to the next generation. These public

school attitudes survived unchallenged until the 1960’s. By then, the public

school accent had become universally the English of radio commentators and

television interviewers. A lot of people I the Labour Party said that public

schools should be abolished because they had produced snobs. Some people

thought it helped to make class distinction all the greater. Superficially,

this is still unchanged. 20 years later, the right words and the right accent,

a world away from Cockney, are still important for a successful career. The new

boys are still drilled in

-

battlings: weekly pocket money

-

mugging: swotting up

-

cripple: punishment given by a prefect or don

-

bartering: cricket fielding practice

-

Jupiter: a notorious rascal at St. Cross, long-since

defunct

-

Pitch up: one’s parents or relations

Dr.

Johnson Wells is an expert in the evolution of British accents. But even in 20

years there have been some significant changes in public school English. There

are 2 differences in the voice quality: before, they were tense in the larynx

and they have a creaky voice (which isn’t like that now). One thing is the “a”

vowel, like in words like “trap”. The /u:/ vowel and the change in its

pronunciation shows that it’s become smart to go downmarket. People are now

embarrassed to be seen to be imitating upper-class behaviour, and this is

reflected in their pronunciation. Students speaking RP curiously show signs of

Cockney influence. Cockney is the most interesting source of new pronunciations

coming in (and it’s been like that for 500 years). Some new pronunciation

arises in Cockney and later people imitate it and becomes RP, and later it is

old-fashioned and disappears. There is a constant change over centuries.

9-4-09

Thomas

Sprat's The History of the Royal Society, 1667.

Thus they have

directed, judg'd, conjectur'd upon, and improved Experiments. But laſtly,

in theſe, and all other Buſineſſes, that have come under

their Care; there is one thing more, about which the Society has been moſt

ſolicitous; and that is, the Manner of their Difcourſe; which,

unleſs they had been very watchful to keep in due Temper, the whole ſpirit

and vigour of their Deſign, had been ſoon eaten out, by the

Luxury and Redundance of Speech. The ill Effects of this Superfluity of

Talking, have already overwhelm'd moſt other Arts and Profeſſions,

inſomuch, that when I conſider the means of happy Living, and

the Cauſes of their corruption, I can hardly forbear recanting what I ſaid

before; and concluding, that Eloquence ought to be baniſh'd out of

all civil Societies, as a thing fatal to Peace and good Manners. To this

Opinion I ſhould wholly incline, if I did not find, that it is a Weapon,

Which may be as eaſily procur'd by bad Men, as good;and

that, if theſe ſhould only caſt it away, and thoſe retain

it; the naked Innocence of Virtue would be, upon all Occaſions,

expos'd to the armed Malice of the Wicked.

This is the chief Reaſon,

that ſhould now keep up the Ornaments of Speaking in any Requeſt, ſince

they are ſo much degenerated from their original Uſefulneſs.

They were at first no doubt, an admirable Inſtrument in the Hands of wife

Men; when they were only employ'd to deſcribe Goodness, Honefty,

Obedience, in larger, fairer, and more moving Images; to repreſent Truth,

clotah'd with Bodies; and to bring Knowledge back again to our very Senſes,

from whence it was at firſt deriv'd to our Underſtandings. But now

they are generally chang'd to worſe Uſes; they make the Fancy disguſt

the beſt Things,

if they come ſound

and unadorn'd; they are in open

Purpoſe, to point

out, what has been done by the Royal Society, towards the correcting of

its Exceſſes in natural Philoſophy; to which it is, of

all others, a moſt profeſt Enemy.

They have therefore

been more rigorous in putting in Execution the only Remedy, that can be found

for this Extravagance; and that has been a conſtant Reſolution,

to reject all the Amplifications, Digreſſions, and Swellings of

Style; to return buck to the primitive Purity and Shortneſs, when

Men deliver'd ſo many Things, almoſt in an equal Number of Words.

They have exacted from all their Members, a cloſe, naked,

natural way of Speaking; poſitive Expreſſions, clear Senſes;

a native Eafſineſs, bringing all Things as near the

mathematical Plainneſs as they can; and preferring the Language of

Artizans, Countrymen, and

Merchant, before that

of Wits,or Scholars.

21-4-09

Spelling

reform

● Chancery English (Mid14th Century)

The Chancery clerks fairly

consistently preferred the spellings which have since become standard … At the

very least they were trying to limit choices among spellings, and that by the

1440s and 1450s they had achieved a comparative regularization. (J.H. Fisher et

al., An anthology of Chancery English, 1984).

Chancery Spelling Other spellings

_ such(e) sich, sych,

swich

_ much(e) moch(e),

myche(e)

_ whiche(e), whyche(e)

wich, wech

_ not/noght nat

_ many meny

_ any eny, ony

_ if/yf yif, yef

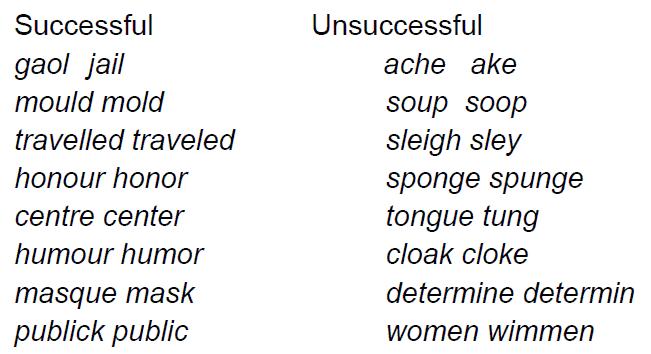

● Hart’s Ortographie, 1569

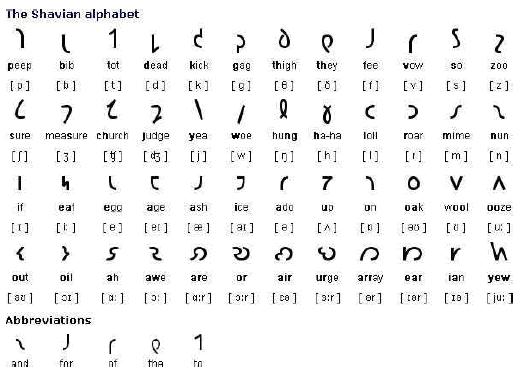

● George Bernard Shaw

To illustrate the

absurdity of English spelling, George Bernard Shaw suggested spelling the word

fish "ghoti."

-“gh” may pronounced /f/ as in laugh.

-“o” may be pronounced /i/ as in women.

-“ti” may be pronounced /sh/ as in nation.

For Shaw, reform of

the alphabet meant saving effort but laypersons were used to the alphabet and

against change:

“the waste does not

come home to the layman. For example, take the two words tough and cough.

He may not have to write them for years, if at all. Anyhow he now has tough and

cough so thoroughly fixed in his head and everybody else's that he would

be set down as illiterate if he wrote tuf and cof; consequently a

reform would mean for him simply a lot of trouble not worth taking. Consequently

the layman, always in a huge majority, will fight spelling reform tooth and

nail.”

… take the words though

and should and enough: containing eighteen letters. Heaven

knows how many hundred thousand times I have had to write these constantly recurring

words. With a new English alphabet replacing the old Semitic one with its added

Latin vowels I should be able to spell t-h-o-u-g-h with two letters,

s-h-o-u-l-d with three, and e-n-o-u-g-h with four …

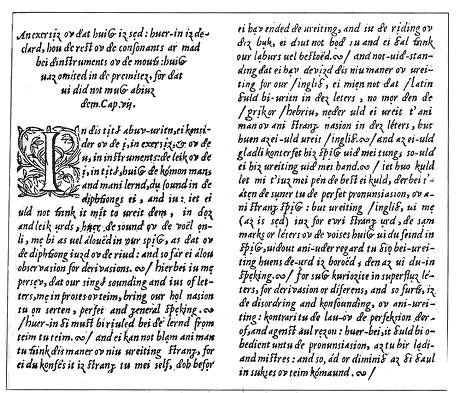

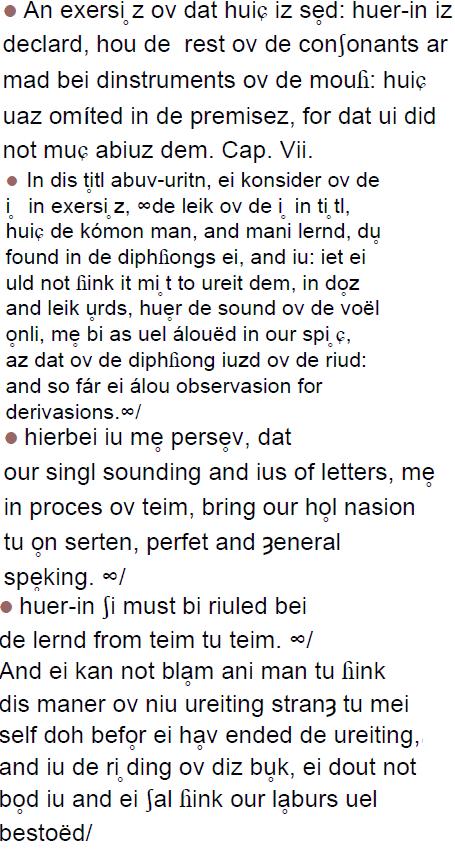

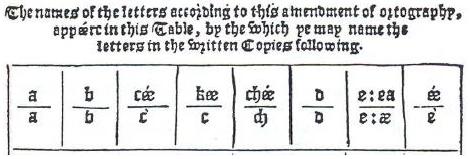

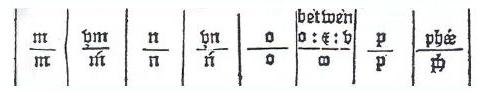

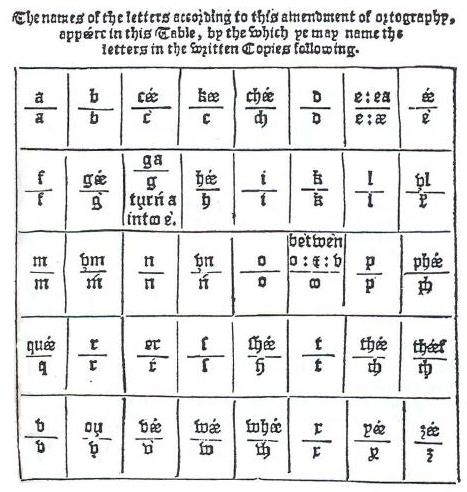

Bullokar’s

Book at Large, 1580 (Adapted from

Freeborn From Old English to Standard English 2nd ed.,

298-299)

There is evidence of these

two contrasting pairs of front and back vowels in another 16th-century

orthoepists (writers on pronunciation) William Bullokar's. The page from his Boke al Large (1580), shows an ‘amendment of

ortography' (revised alphabet) with separate letters proposed for the long

vowels [e:], [ɛ:], [o:] and [ɔ:]. It is clear that in the late 16th century they were still separate

phonemes.

The letters for the

two mid-front vowels [ɛ] and [e] (short and long) are

shown at the end of the top row (see diagram below) as (e:a)

and (e').

Words containing these

letters in Bullokar's text in his new spelling include, for example

<e> = [ɛ] sent, qestion, terror

sent, question, terror

<a>

= [ɛː] mæning,

thærfore, encræse, decræse, whær, læu

meaning, therefore, increase, decrease, where, leave

<e’> = [eː] bre’f, agre’, be’, be’ing,

e’nglish, ke’p, we’, ye’ld

brief, agree, be, being, English, keep, we, yield

Letters for the

mid-back vowels, approximately [ɔ] and [o] (short and long) are in

the third row (see diagram below), (o) and (oo).

Letter (oo) is glossed

'betwe'n o & u', which is evidence of the raising of long [oː] towards [uː]. Examples are,

<o> = [ɔ] qestion (3 syllables),

prosody, diphthong, wronged

question, prosody, diphthong, wronged

<o>

= [ɔː] wo, on

woe, one

<oo> = [oː]-[uː] untoo, too, dooth

unto, to/too, doth

Dictionaries

DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON

-

Dates and statistics

-

The plan of the dictionary published in 1747

-

Dictionary completed in 1755

-

Definitions of 40,000 words

-

114 quotations to

illustrate usage

● Objectives:

- To fix the English language although language is the work of man, of a being from

whom permanence and stability cannot be derived… tongues, like governments,

have a natural tendency to degeneration; we have long preserved our

constitution, let us make some struggles for our language.

Those who have been

persuaded to think well of my design, will require that it should fix our

language, and put a stop to those alterations which time and chance have

hitherto been suffered to make init without opposition. With this consequence I

will confess that I have indulged expectation which nether reason nor

experience can justify.

(from the Preface to Dr Johnson’s Dictionary, 1755)

- To preserve the purity and

ascertain the meaning of our English idiom.

- To provide a dictionary for popular use.

● Criteria used in preparing the dictionary:

- The inclusion of

foreign words: the peculiar words of

every profession; the names of species –even though they required so their accents should be settled, their sounds ascertained, and their etymologies deduced.

- To settle the

orthography, or spelling of words: The chief rule which I propose to follow,

is to make no innovations, without a reason sufficient to balance the

inconvenience of change; and such reason I do not expect often to find.

- To produce a guide to pronunciation –the accentuation of polysyllables

and the pronunciation of monosyllables.

- To consider the etymology or derivation of words.

- Interpreting the words with brevity, fullness and perspicuity.

- Assigning words to classes –general, poetic, obsolete, used by

individual writers, used only in burlesque writing, impure and barbarous.

He is credited with standardizing spelling although his spellings gave

precedence to preserving a word's etymology or origin rather than its sound.

Lexicographer, ‘a writer of dictionaries, a harmless drudge’

Johnson declared his

intention to“ascertain” or fix pronunciation, “the stability of which is of

great importance to the duration of a language” (1747: 11).

When the dictionary was

published, eight years later, entry words came only with an indication of

stress-position, hence CO'MELY or INDETERMINA'TION.

To FRE'NCHIFY. v. a.

[from French.] To infect with the manner of

They miſliked

nothing more in King Edward the Confeſſor than that he was

Frenchified; and accounted the deſire of foreign language then to be a

foretoken of bringing in foreign powers, which indeed happened.

Has he familiarly diſlik'd

Your yellow ſtarch,

or ſaid vour doublet

Was not exactly Frenchified?

Shakſp.

COUGH, n.ſ. [kuch,

Dutch.] A convulſion of the lungs vellicated by ſome ſharp feruſity.

It is pronounced coff. In conſumptions of the lungs, when nature cannot

expel thr cough, nen fall into fluxes of the belly, and then they die. Bacon’s

Natural Hiſtory. For his dear ſake long reſtleſs

nights you bore, While rattling coughs his heaving veſſels tore.

Smith

NOAH WEBSTER AMERICAN DICTIONARY

OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE (1828)

Webster resented the fact that

He thought the English in

His books were based on the republican principle of popular sovereignty.

The essential feature of the dictionary is its historical method, by which

the meaning and form of the words are traced from their earliest appearance on

the basis of an immense number of quotations, collected by more than 800

voluntary workers.

The dictionary contains a record of 414,825 words, whose history is

illustrated by 1,827,306 quotations.

- 1933-1986: Supplements to the OED

- 1980s: The Supplements are integrated with the OED to produce

its Second Edition.

- 1992: The first CD-ROM version of the OED is published.

- 1992: The first CD-ROM version of the OED is published.

- James Murray (1837-1915)

- Henry Bradley (1845-1923)

- William Craigie (1867-1957)

- C.T. Onions (1873-1965)

- Robert Burchfield (1923-2004)

- Edmund Weiner (b. 1950)

- John Simpson (b. 1953)

COBUILD DICTIONARY

The first COBUILD

dictionary was published in 1987.

It was the first of a

new generation of dictionaries that were based on real examples of English -

the type of English that people speak and write every day.

Collins and the

The corpus, known as

the Bank of English™, became the largest collection of English in the world and

COBUILD uses the corpus to analyze the way that people really use the language.

28-4-09

Video

about Shakespeare

Queen

For

many years, one of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s leading directors was John

Barton.

Shakespeare

is the most comprehensive genius in terms of sensibility and understanding of

humanity. He had the greatest means of expressing that breadth.

It’s

impossible to quantify the relationship between the development of the language

and a writer of genius like Shakespeare. The First Folio of his plays, the

source for scores of Shakespearian words and phrases had a direct influence on

every one of us who speaks English today. He had an inexhaustible passion for

words; he has the largest vocabulary of any writer of English, approximately

34.000 words, which is about double what an educated person uses today in their

lifetime. In one famous passage, Shakespeare uses only two words. As well as multitudinous and incarnadine, the long list of words and uses include: accommodation, premeditated, assassination,

submerged, and obscene.

In

Loves Labours Lost he could almost have been writing his own epitaph when he

describes Armando as a man of “fire-new words”.

Shakespeare

spelled his name in many different ways. Spelling was a matter of taste. He

invented more words than anyone and no one apparently commented on that at the

time. So there was a lot of creative freedom. The actors who spoke his lines

also found him playing with the grammar of English. Nouns could become verbs.

But, above all, Shakespeare gave the

Video

about The Bible

This

golden age also saw the publication that has probably had an even greater

influence than Shakespeare’s First Folio on the language of ordinary

people. The translation of the Bible

into the English of The Authorised Version. Here at last was expressed the word

of God in terms that everybody could understand. Where Shakespeare drew on his

teeming vocabulary of 34.000 words, the new translation achieved the majestic

effects of its prose with barely 8000.

It’s

an interesting reflection on the state of the language that the poetry of the

Authorised Version came not from a single writer, but from a committee, some of

whom worked here, at the

Contemporary

with the King James’ Version of the Bible was The Book of Common Prayer, which

expresses the rites of passage in the

29-4-09

Video

about the demise of Cockney and the rise of RP

What

we call Cockney speech today, in its backbone, was the speech of the citizens

of

Up

to the 18th century, up to say about 1750, Cockney was the speech of

anybody and everybody in the city of

Video

about RP up to World War II

Varieties

of English are as old as the language itself. In fact, the idea of a correct or

proper way to speak is surprisingly recent. There is such an idea, of course;

it is often referred to as the Queen’s

English, BBC English, Oxford English or Public School English.

Public

School English is barely 100 years old. It first echoed round the playing

fields of schools like Eton, Harrow and

You

had a kind of unnatural segregation of a subset of people of the country, the

very people who are going to become the most powerful. Because of their

position of power, they were the basis of imitation. They were eminent and

eminently imitable, as it were. The presumed superiority of this accent

lingers. Research in

The

invention of the wireless turned public school English into BBC English. The

radio did for the spoken language what printing had done for the written.

Listeners could hear for the first time a definitive English speech. The voice

of information, culture, and the

World

War II was the finest hour for the BBC English. The voice of

21-5-09

Unit 4. Expansion of English

EXPANSION OF ENGLISH

l

There was no

l

l

Most of

l

Geographically

divided into

-

Southern Uplands

-

Lowlands

-

Highlands

l

In pre-history inhabited by Picts

l

Scots, Celts from

l

By 700 Anglo-Saxons conquered most of

l

l

Union of the crowns of

l

English and Scottish Parlaiments unified in 1707 (Act

of Union)

l

“Dress act” designed to disarm and finish off clan

culture (1746) after Jacobite Rising.

l

Highland Clearances 18th, 19th centuries.

Gaelic-speaking population evicted from land.

l

After 1066 the

l

Edward 1st (1272) In 1277 massive invasion.

l

By 1290s Wales virtually an English colony.

l

King Edward Ist gave his son, (Edward II), the title

Prince of Wales in 1301.

l

King Henry VIII, joined

l

Norse kingdom established in

l

Viking influence is checked in 1014 but they remain in

l

Norman nobles invade

Ireland 1169-1170.

l

Henry II invades. Pope Adrian IV grants him authority

over

l

1210-1300 English

Government in Ireland.

l

Celtic uprising 1315-1318. Edward Bruce, king of

l

Henry VII, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I strengthen English

control of

l

The plantation of

Ireland: 1586-1641

l

Scottish

Presbyterian settlers.

UNITED STATES

l

The Colonial

Period (1607–1776)

l

Humphrey Gilbert claimed the

l

Walter Raleigh’s failed settlement at

l

Jamestown 1607

l

Plymouth colony 1620

l

Maryland colony 1634

l

Colonization of the

l

The Dutch settled

l

Quaker colony

AMERICAN ENGLISH

l

l

Virginia Settlers mainly from West Country of England.

UNITED STATES

ENGLISH TODAY

l

American English

l

General American (rhotic)

l

Southern States

(non-rhotic), (drawl,

l

New England (non-rhotic)

l

l

African American Vernacular English

l

Spanglish

l

Peace of

l

The rest of New France conquered by

l

40,000 Loyalists arrived in

l

Dominion of

CANADIAN ENGLISH

l

Virtually indistinguishable from American English due

to influence of southern neighbour.

l

Use of “eh”

l

Diphthong for words like about, knife have not

been lowered as in RP and General American.

l

No distinction between initial /hw/ and /w/, making which/witch

homophones.

l

The first permanent British settlement on the African

continent was made at

l

l

Cape of Good Hope (now part of

l

The British East Africa Protectorate was established

in 1896:

l

Zanzibar, Tanzania

(after WWI)

ENGLISH IN

l

English is an official language of 16 countries:

l

in West Africa

l

in East Africa

l

in Southern Africa

l

In

l

Standard English occupies a privileged place in the

stratification of languages in these regions, but is largely a minority

language learned mainly through formal education. (Concise Oxford Companion to the English Language)

l

Early incursions by privateers John Hawkins and Sir

Francis Drake brought three boatloads of slaves to the Spanish colonies from

l

First British settlements: St Kitts in 1623 (Thomas

Warner);

l

ENGLISH-SPEAKING

l

12 independent countries: Antigua and Barbuda, The

Bahamas, Barbados, Belize (on the Central American mainland), Dominica,

Grenada, Guyana (on the South American mainland), Jamaica, Saint

Kitts/Nevis (known also as Saint Christopher/Nevis), Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent

and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago.

l

6 dependent territories: Bermuda, British Virgin

Islands, Cayman Islands, Anguilla, Turks and Caicos Islands, and

l

Standard English: used by a minority. Now lots of

American influence.

l

Creoles based on European lexicons and with African

substrates.

l

The English-based creoles can be viewed as dialects of

English or languages in their own right.

l

Mesolect: Somewhere between creole and localized

English.

l

Clive defeated the French company and captured

l

Power transferred from the English East India Company

to the British Crown (1858)

l

l

Pakistan: Urdu

(official); Punjabi; Sindhi; Pashtu; English

l

Captain James Cook claimed

l

British penal colony of

l

Tasmania settled in

1803

l

AUSTRALIAN

ENGLISH

l

London English dominant but settlers from all parts of

l

Most marked characteristic: Homogeneity but varieties

go from Broad Australian, General Australian, and Cultivated

Australian.

l

New Zealand English indistinguishable from Australian

to most outsiders.

Videos

African-English

creoles.

This

West African bauxite mine is owned by the Swiss multinational Alles Swiss. But

English is the day to day language of operations. Most of the people here are

speaking English quite fluently; maybe it’s not a classical English but it’s

English. So it’s the only means of communication.

There

is quite a high turn over in our company, that means after four, five or six

years the people are leaving the company. Who will replace them? Nobody knows.

The German may be replaced by an English, an English may be replaced by a

German, so we have to use a language that is common for everybody, and this

language is of course English.

The

miners here speak six different African languages. So they talk Creole English

to each other.

Arrival

in

Sir

Walter Raleigh, who had this farm in Devon, rolled his

In

1584 Raleigh, who had always dreamed of setting up English cities overseas,

sent two ships across the

A

settlement was established at a place they called

But

the

Almost

a generation later in 1607, three more English ships, like these, anchored in

six fathoms of water off a wooded island. The sailors called it

Many

of the Virginians who lived here, in

The

speech of

The

first penal settlements in

The

convicts also adopted Aborigine words like kangaroo,

wallaby, bandicoot, budgerigar, wombat, koala and dingo.

Convicts

and aborigines meeting for the first time communicated in pidgin English. The

Australianism walkabout is an early

example of pidgin English Down Under. Among the convicts, the first visitors to

Australian

linguist, professor John Bernard: the greatest number came from

Manifestos

of the First Fleet showed that convicts came from every county of England,

Scotland and Ireland, and so many of the words which Australians think are

Australian, are in fact county words of Great Britain. Words like cobber (meaning a friend. Came from

The

bulk of the early Europeans in Australia were, of course, convicts, and they

brought with them the “flash language”, which was a highly developed jargon

which the criminal classes used and which I suppose the people who weren’t

quite criminal, but had been convicted, learnt on the ships. And the

consequence was that there was an early complaint from the magistrates that

they couldn’t understand what was being said in their own courts. And Flash Jim

Vaux, who managed to get himself transported three times, in 1812 wrote a short

vocabulary of the Flash Language ostensibly to help the magistrates.

With

their ticket of leave, released convicts joined the pioneering free emigrants,

drovers, stockmen and grazers in the bush

or the outback. With them went flash

talk, words like swag and swagman. The first squatters established

huge sheep farms known as stations. Here words like jumbuck for a sheep and tucker

for food soon gave a distinctive flavour to Australian English.

George

Hawker’s ancestors were army officers who settled in Bungaree, north of

In

Canadian

English.

What’s

so funny about the way Canadians say “about”?

The

pronunciation of words like about and house in RP would be ǝbaut and haus,

but in Canadian English it is ǝbǝut and hǝus.

English

in

The

African sun set on the Union Jack but not on the English language. Africa needs

a link language even more than

The

African nations with hundreds of languages need a lingua franca. And 16

countries have retained English since the de-colonization. English creoles are

spreading rapidly throughout the markers and bazaars of

And

Standard English is taught in

Highlanders.

The

highlands and Islands of Scotland: Celtic culture and Gaelic language.

Since

the 18th century, Scottish Gaelic has been driven almost to

extinction. It survives on remote islands like Barra in the

When

we hear a Gaelic speaker speaking in English, it would resemble Irish because

the source is the same, as regards the Irishmen as it is for the

Highlander/Islander, that is Gaelic. And it has the same rhythm, and very often

similarity of construction…

The

English spoken here is a beautiful sweet sounding, rolling, soft type of

English. It is a very comforting sound compared with the whiskied, fast moving

accents you get from the cities and towns. The people from Barra speak Gaelic

as freely as English, but their language faces extinction. In these places you

can see the wounds inflicted by world English on a traditional local culture.

Gaelic is their ancestral tongue, but even there, they sometimes drop into

English.

Highlanders

after Culloden.

Scots

Gaelic has been a persecuted language ever since the revolt of 1745 led by

Bonnie Prince Charlie was defeated when the ill-equiped Highlanders were mowed

down by the British artillery at the battle of Culloden, the subject of this

early television documentary. In reality the rebellion was small. But

Highlanders have never forgotten that it was used as a pretext to impose the

English way of life. After Culloden, the laws that were enacted were ordained

really to destroy the way of life, the language and the customs of the

Highlanders and Islanders. The Highlander wasn’t permitted to practise his

language or to wear his native dress (like the kilt nowadays), to carry arms

(which was quite significant for them then), to be educated through the medium

of Gaelic. It made it very difficult for the Gaelic culture to survive.

The

Indian

English.

With

its 14 compelling linguistic traditions,

Puritans.

Farther

north of James Town around the