BIOGRAPHY

INTRODUCTORY NOTES

Nearly all our information about the first forty-six years of Sterne's

life before he became famous as the author of Tristram Shandy is

derived from a short memoir jotted down by himself for the use of his

daughter. This memoir gives nothing but the barest facts, excepting

three anecdotes about his infancy, his school days and his marriage.

Conversely, for the last eight years of his life, after the sudden leap

out of obscurity caused by his literary success, we have a faithful

record of Sterne's feelings and movements in letters to various persons

(published in 1775 by his daughter, Lydia Sterne de Medalle) and in the

1766-1767 Letters from Yorick to Eliza (also published in 1775) (1).

Laurence Sterne

was the great-grandson of Richard Sterne, Archbishop of York and Master of

Jesus College, Cambridge.

Laurence's father, Roger Sterne, was a Yorkshire soldier who served as an

officer in Flanders under the Duke of

Marlborough during the War of the

Spanish Succession

(1701-1714). His mother, Agnes, the widow of another English army officer,

married Roger Sterne while he was on campaign in Dunkirk in 1711.

Laurence was born on 24 November 1713 at Clonmel, Co. Tipperary

(Ireland),

where his father's regiment was stationed. Sterne spent his early childhood

following the regiment's many transfers both in Ireland and England, and this

close contact with military life would later inspire him for the creation of

some of his most notable comic characters (especially Uncle Toby, Corporal Trim

and Lieutenant Le Fever in Tristram Shandy).

In 1723, after ten years of wandering (Dublin,

Devonshire, Isle of Wight, County Wicklow, Mullingar), Laurence was handed over to a

relation in Elvington (Yorkshire), and sent to a grammar-school at Hipperholme,

near Halifax,

where he learned Latin and Greek. In 1727, Sterne's father was

seriously wounded in a duel. He never fully recovered from the wound and died

suddenly in March 1731 .

In July 1733,

Sterne was admitted at Jesus College, Cambridge,

where his great-grandfather (the Archbishop) had been master. He took his B.A.

degree in 1736 and proceeded M.A. in 1740. In his last year, a haemorrhage of the

lungs was the first sign of the consumption that was to trouble him for the

rest of his life.

Meanwhile,

young Sterne had took orders, and in 1738, through his uncle's influence

(Jaques Sterne was choirmaster and canon of York),

obtained the living of Sutton-on-the-Forest, about eight miles north of York.

In 1741 Sterne

married Elizabeth Lumley, a cousin to Elizabeth Montagu, the bluestocking, and

in 1747 their daughter, Lydia,

was born. Living the life of a rural parson, Sterne kept his residence at

Sutton for about two generally uneventful decades. During these years he kept

up a close friendship which had begun at Cambridge with a distant cousin from

Yorkshire, John Hall-Stevenson (1718-1785), a witty and accomplished epicurean,

owner of Skelton Hall (also known as “Crazy

Castle”), in the Cleveland district of Yorkshire.

Skelton Hall is

nearly forty miles from Sutton, but Sterne, in spite of his double duties (he

was also vicar of the neighbouring living of Stillington and prebendary, or

canon, of York Minster), seems to have been a frequent visitor there, and to

have found in his rather eccentric friend a highly congenial companion. Sterne

is thought to have never formally become a member of the circle of merry

squires and clerics at Skelton known as “The Demoniacks”, but certainly he must

have shared their revelries on and off

In 1747 Sterne

published a sermon preached in York

under the title of The Case of Elijah. This was followed in 1750 by The Abuses

of Conscience, afterwards inserted in Vol. II of Tristram Shandy. In 1759 he

wrote a sketch on a quarrel between his Dean and a York lawyer, a sort of Swiftian satire of

dignitaries of the spiritual courts which gave an earnest of Sterne's powers as

a humorist. At the demands of embarrassed churchmen, however, the book was

burned: thus, if on one hand Sterne lost his chances for clerical advancement,

on the other he ended up discovering his real talents

Sterne's

marriage, which had never been truly happy, reached a crisis in 1758, when his

wife, after learning of an affair with a maid-servant, had a nervous breakdown

and was eventually placed under the care of a doctor in a private house in York. As Sterne's own

health continued to fail, he progressively fell into a state of melancholy: it

was in this atmosphere of gloom and despondency that The Life and Opinions of

Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, one of the most light-hearted books in the whole of

literature, was begun. Sterne completed fourteen chapters in six weeks and

promised to write two volumes a year for the rest of his life. A first, sharply

satiric version of the novel was initially rejected by the London printer Robert Dodsley. Sterne continued his comic novel,

but every sentence, he said, was “written under the greatest heaviness of

heart”. In this mood, he decided to soften the satire and describe Tristram's

opinions, his eccentric family, and ill-fated childhood with a sympathetic

humour, sometimes hilarious, sometimes sweetly melancholic – a comedy skirting

tragedy.

Sterne himself

published the first two volumes of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy,

Gentleman at York

late in 1759, but he sent half of the imprint to Dodsley. By March 1760, when

he went to London,

Tristram Shandy was the rage, and Sterne became instantly famous. The news of

his presence there soon spread, visitors thronged to his rooms in St Alban's Street,

and invitations to fashionable dinners and receptions abounded. The witty,

naughty “Tristram Shandy”, or “Parson Yorick”, as Sterne was called after

characters in his novel, was the most sought-after man in town: London was charmed with

his audacity, wit and graphic unconventional power. However, he was also much

criticized: while Dr. Johnson, who did not appreciate his use of indecent

allusions, mistakenly declared “Nothing odd will do long”, readers from York

were particularly scandalized at its clergyman's indecency, and indignant at

his often scurrilous caricatures of well-known local figures, such as the male

midwife Dr. Slop.

When a second

edition of the first instalment of Tristram was called for in three months, two

volumes of Sermons by Yorick were also announced. Although they had little or

none of the eccentricity of the history, they proved almost as popular (in the

novel, Sterne had portrayed himself in the character of Parson Yorick). Lord

Fauconberg presented the author of Tristram Shandy with the perpetual curacy of

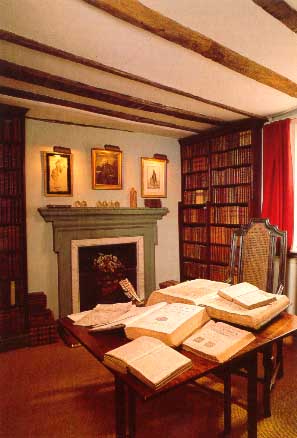

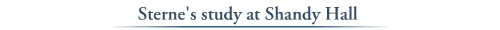

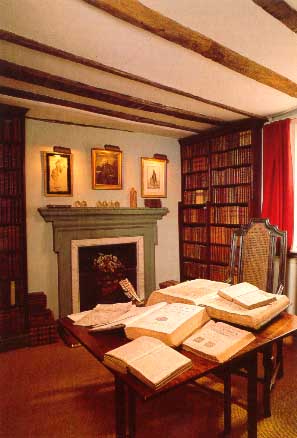

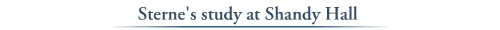

Coxwold, and in the summer of 1760 the Sterne family returned to Yorkshire, where they moved into a charming old cottage,

renamed “Shandy Hall” after Sterne's literary hero

Sterne wrote

two more volumes of Tristram Shandy and, the following Christmas, he returned

to London to

superintend their publication. These volumes appeared in January 1761, to the

same chorus of praise and criticism as the earlier volumes. Fashionable society

welcomed him back and for another three months he was immersed in social life. When

he returned to “Shandy Hall”, he continued to work on Tristram Shandy, and the

fifth and sixth volumes were completed by December 1761. While supervising the

publication of these volumes in London, he

suffered a severe haemorrhage of the lungs, and a journey to the south of France was

hastily arranged for his health's sake. Obtaining a year's absence from his

post from the Archbishop of York, he left for Paris in January 1762. This and a later trip

abroad gave him much material for his later Sentimental Journey.

Sterne's fame

had preceded him to Paris and he was welcomed in

much the same way as he had been in London.

His health temporarily improved, and, in May 1762, he sent for his wife, now

recovered, and his daughter, who was suffering from asthma. In July, following

a relapse of his health, they left for Toulouse,

where they stayed for a year. Sterne spent the year writing a seventh volume of

Tristram Shandy, incorporating some of his experiences in France into the

story. In July 1763, the family visited the Pyrenees, Aix-en-Provence

and Marseilles, and in September 1763, they

settled in Montpellier

for the winter. In March 1764 Sterne resolved to return to England, but his wife did not share his desire

to leave and decided to stay in France

with Lydia,

while she completed her education. Having accepted his wife's wish, Sterne

spent most of the summer in London, and then returned to Shandy Hall in the

autumn, where he soon immersed himself in an eighth volume of Tristram Shandy. The

seventh and eighth volumes were published on 26th January 1765.

In October

1765, Sterne set out for a seven months' tour through France and Italy,

which was later immortalised in his second novel, A Sentimental Journey through

France and Italy, by

Mr.Yorick. He passed through Paris and Lyons to Turin,

where he began his tour through Italy

in the company of Sir James Macdonald, a cultivated young man then resident in Italy. He

visited Milan, Parma,

Florence, Rome

and Naples, and, on his return through France, he

visited his wife and daughter. Elizabeth

had decided that she could manage better without him, and begged to stay abroad

for another year. Thus, in June 1766 Sterne returned alone to Yorkshire

for the second time, where his main companion, now that he was separated from

his family, was his old friend John Hall-Stevenson. By this time Sterne was

seriously short of money, having spent most of his literary earnings on his

foreign tours. Having a family abroad to support, he set about repairing his

financial position, by means of the sales of the ninth and final volume of

Tristram Shandy (completed in the autumn).

In December

1766, Sterne was in London

again, where he met Mrs. Eliza Draper, the wife of Daniel Draper, an official

of the East India Company, and fell in love with her. They carried on an open,

sentimental flirtation, but Eliza was under a promise to return to her husband

in Bombay. Sterne

never saw her again, but he was not willing to let the relationship go. He sent

her his books, and, having had her portrait painted, wore it round his neck. With

half an eye on posterity, he kept a"Journal to Eliza", modelled on

Swift's Journal to Stella, and also A Sentimental Journey is full of references

to Eliza, to the portrait, and his vows of eternal fidelity to her.

On returning to

Yorkshire, he was visited by his wife and daughter in August 1767, but, since

they continued to find each other's company insupportable, he and his wife

finally came to an agreement that she and Lydia

should return to the South of France, with an improved financial allowance, and

never return to England.

Sterne seems to have been content with this arrangement, although he also seems

to have been upset at being parted from his daughter, for whom he had a genuine

affection. By December 1767, two volumes of A Sentimental Journey Through France

and Italy, by Mr. Yorick,

were completed, and Sterne set off with John Hall-Stevenson for London to superintend

their publication early in 1768.

In March, he

fell ill with influenza, and on the 18th he died.

Legend has it

that soon after burial at London, Sterne 's body

was stolen by grave robbers and sold for the purpose of dissection to the

professor of anatomy at Cambridge.

Luckily, his features were recognised by a student at the dissecting table, and

the body was quietly returned to the grave.

Notes

(1)The holograph manuscript of Sterne's memoir – Sterne's Memoirs:

A Hitherto Unrecorded Holograph Now Brought to Light in Facsimile, with

introduction and commentary by Kenneth Monkman (Coxwold, privately

printed for The Laurence Sterne Trust, 1985) – is now on permanent loan

to “Shandy Hall”, Coxwold. A detailed biography (TRAILL, H. D.,

“Sterne”, English Men of Letters Series, 1882) is available online: <http://www.authorama.com/sterne-1.html>.

A more recent and equally thorough source of reference is: ROSS, Ian

Campbell,Laurence Sterne: A Life (Oxford: OUP, 2001). For a selection

of Sterne's correspondence: CURTIS, Lewis Perry, ed., Letters of

Laurence Sterne (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935, 1967²)

(2) “When we read over the siege of Troy, which lasted ten years and eight

months, -- though with such a train of artillery as we had at Namur,

the town might have been carried in a week -- was I not as much

concerned for the destruction of the Greeks and Trojans as any boy of

the whole school? Had I not three strokes of a ferula given me, two on

my right hand and one on my left, for calling Helena a bitch for it?

Did any one of you shed more tears for Hector? And when king Priam came

to the camp to beg his body, and returned weeping back to Troy without

it, -- you know, brother, I could not eat my dinner” (Tristram Shandy,

Vol. VI, Ch. XXXII).

(3) John Hall-Stevenson's various occasional sallies in verse and prose -

his Fables for Grown Gentlemen (1761 - 1770), Crazy Tales (1762) and

Makarony Fables (1767), which were all mainly political sketches

against the opponents of John Wilkes, the parliamentary reformer - were

collected after his death, and it is impossible to read them without

being struck with their close family resemblance in spirit and turn of

thought to Sterne's work, inferior as they are in literary genius.

Hall-Stevenson was also said to be the original of Eugenius in Tristam

Shandy. For a commentary on Hall-Stevenson's Crazy Tales, see <http://www.bartleby.com/221/0820.html>.

(4)The sketch would not be published until 1769, the year after Sterne's

death, when it appeared under the title A Political Romance (and later

The History of a Good Warm Watch-Coat).

(5)“Shandy Hall” is now a museum.

(6)The story, only whispered at the time, was confirmed in 1969: Sterne 's

remains were exhumed and now rest in the churchyard at Coxwold, close

to Shandy Hall.

© "Laurence Sterne" The Tristram Shandy Web. Biography by Diego Sorba. 1 Nov 2008

http://www.tristramshandyweb.it/sezioni/sterne/biography/sorba_biography.htm#2a

More biographies [Next] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10]

- Index -