HISTORY OF ENGLISH

CONSONANTS: SOUND & SPELLING

There are three different types of phonetics:

1. Productive phonetics: how the sound is made.

2. Acoustic phonetics: phonetics as a physic phenomenon.

3. Auditory phonetics: the sounds we hear make us react in different ways.

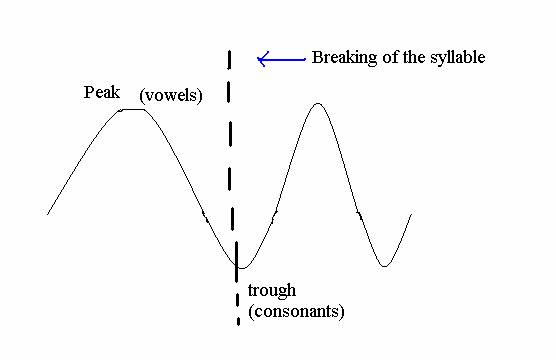

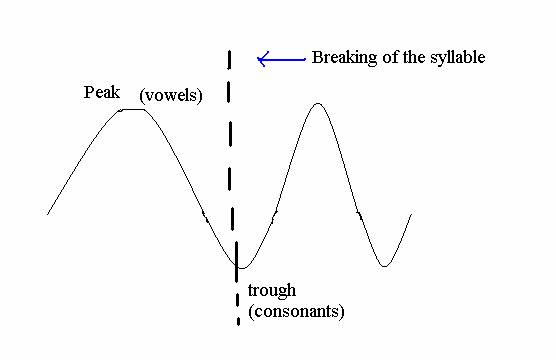

A phonetic language is a language in which spelling and pronunciation fit in most cases. In these kinds of languages the “trough” begins from the following syllable. The English language is not a phonetic language. The “Trough” starts the previous syllable. For example: mutt-on. In mutton the “o” is not pronounced, that’s the reason why the “n” is syllabic.

The Indo-European consonant system had a large inventory of stops (plosive consonants). Their pronunciation was labial (involving the lips), coronal (involving the tip of the tongue) or dorsal (involving the back part of the tongue). Dorsal stops can be further classified into palatal (‘soft’, a bit like English /k/ in cube), plain (or simple velar, like /k/ in cut), and labiovelar (with lip rounding, like /kw/ in quote). The letters y and w in this system have no other function apart from marking the palatal or labialised character of the preceding consonant; they are not used to stand for independent speech segments. We mention here the IE palatals (and put them in the table below) because most reconstructions found in the standard handbooks require them in the protolanguage. However, it is not quite clear if they could really contrast with ‘plain’ velars; we’re inclined to think they couldn’t, so in our reconstructions elsewhere on this work you will only find k etc. where many other people reconstruct ky.

IE stops could have any of the following three manners of articulation: simple voiceless (like t), simple voiced (like d), or aspirated voiced (like dh, pronounced with a strong puff of breath). The exact pronunciation of these three types of sound is to some extent a matter of speculation, but it is at least certain that all three are needed to account for the observed contrasts in IE languages.

Here is a table of the stop system:

|

Labial |

Coronal |

Palatal |

Plain Velar |

Labiovelar |

|

p |

t |

ky |

k |

kw |

|

b |

d |

gy |

g |

gw |

|

bh |

dh |

ghy |

gh |

ghw |

There was one sibilant fricative, s, and probably a few more velar or glottal (h-like) sounds, known as the ‘laryngeals’. They are very poorly attested in the historical languages (with the notable exception of the Anatolian languages, e.g. Hittite), but the assumption of their existence in the protolanguage (the ‘laryngeal theory)’ is very important for understanding PIE morphology. We shall use the symbols x, xw, and h to refer to the three ‘laryngeals’ required by most versions of the theory. We consider it likely that x was a velar fricative like Scots ‘ch’ in loch, xw was its labialised counterpart, and h was a glottal ‘aspirate’, just like English /h/.

Many mutations appear when we look at the Germanic substrat. They were systematized by Grimm.

The writing system for the earliest English was based on the use of signs called runes, which were devised for carving in wood or stone by the Germanic peoples of Northern Europe. The best surviving examples are to be seen in the Scandinavian countries and in the islands of Shetland and Orkney. The best known is a large 18-foot high cross now in the church at Ruthwell, Dumfreisshire in Scotland.

THE ANGLO-SAXON RUNES NAME AND SOUND

|

1 = Feo ........ f |

12 = Jara ...... j |

23 = Daeg ...... d |

|

2 = Ur ......... u |

13 = Yr ........ e` |

24 = Otael ...... o |

|

3 = Thorn .... th |

14 = Pertra ... p |

25 = Ac .......... long a |

|

4 = Os ......... short a |

15 = Eolh ...... r |

26 = Asec ....... short a |

|

5 = Rad ....... r |

16 = Sigel ...... s |

27 = Yr .......... y |

|

6 = Ken ....... k |

17 = Tir ........ t |

28 = Ior .......... io |

|

7 = Geofu .... g |

18 = Beroc .... b |

29 = Ear ......... ea |

|

8 = Wynn .... w |

19 = Eoh ....... e |

30 = Cweorp ... qu |

|

9 = Hagall .... h |

20 = Mann ..... m |

31 = Calk ........ k |

|

10 = Nied ..... n |

21 = Lagu ...... l |

32 = Stan ........ st |

|

11 = Is ......... i |

22 = Ing ........ ng |

33 = Gar ......... hard g |

The Anglo - Saxon runes had their own unique

development from 700 AD to 1200 AD. These runes are very beautiful inscriptions.

OLD ENGLISH

After the runic system the Roman alphabet began to be used in order to write in Old English. As we know the Roman alphabet is the one we are used to read and write with. It was used to match letters to the nearest equivalent sound in English. But no Roman letter was available for some OE sounds, so other non-Roman letters were adopted.

Afterwards, we can observe some changes in letter shapes, like:

Regarding length, OE had both short and long consonants. The pronunciation of continuants- that is, consonants that can be held on, like the fricatives [f], [h], [s] - can obviously be made longer or shorter. But plosive (stop) consonants, like [p] and [t], were also doubled in spelling to indicate a pronunciations similar to that of, for example, the MnE <-pp-> combination in a compound word like hop-pole or <-tt-> in part-time, or the sequence –gg- in the phrase big game. Examples: the words hoppian /hop:i�n/, cwellan /kw�l:�n/ or sunne /sun:�/.

Old English sounds

|

OE letter |

OE word |

OE sound (IPA) |

Modern word with similar sound |

|

p |

Pullian (pull) |

[p] |

Pull |

|

b |

Brid (bird) |

[b] |

Bird |

|

t |

Tael (tail) |

[t] |

Tail |

|

d |

do¯¯a (dog) |

[d] |

Dog |

|

c |

Col (coal) |

[k] |

Coal |

|

|

Cirice (church) |

[t∫] |

Church |

|

¯ |

¯ift (gift) |

[g] |

Gift |

|

|

¯eon¯ (young) |

[j] |

Young |

|

|

bo¯ (bough) |

[γ] |

- |

|

c¯ |

hec¯ (hedge) |

[d¯] |

Hedge |

|

x |

Aex (axe) |

[ks] |

Axe |

|

f |

Fot (foot) |

[f ] |

Foot |

|

|

Lufu (love) |

[v] |

Love |

|

s |

Sendan (send) |

[s] |

Send |

|

sc |

Sceap (sheep) |

[∫] |

Sheep |

|

h |

Siht (sight) |

[ç] |

German nichts |

|

|

Boht (bought) |

[x] |

German nacht |

|

l |

Leper (leather) |

[l] |

Leather |

|

m |

Mona (moon) |

[m] |

Moon |

|

n |

Niht (night) |

[n] |

Night |

|

r |

Rarian (roar) |

[r] |

Roar |

|

ρ |

Paeter (water) |

[w] |

Water |

Going ahead with the consonants we get to the Viking settlement and its effects on the English language. Old Norse is the name now given to the group of Scandinavian languages and dialects spoken by the Norsemen. It was cognate with Old English, that is, they both came from the same earlier Germanic language. Many OE words therefore have a similar cognate ON word, and often we cannot be sure whether a MnE reflex has come from OE, or ON, or from both. Here we can observe some examples:

|

Modern word |

OE |

ON |

|

Adder |

Naeddre |

naðra |

|

Bake |

bacan |

Baka |

|

Church |

Cir(i)ce |

Kirkja |

|

Daughter |

dohtor |

dottir |

|

Earth |

Eoþre |

jorð |

|

Father |

Faeder |

faðir |

|

Green |

Grēne |

Groen |

|

Hear |

Hŷran |

Heyra |

|

Iron |

īren |

īsern |

|

Knife/knives |

Cnīf |

knifr |

|

Lamb |

lamb |

lamb |

In relation to Old Norse vocabulary we have to mention the OE digraph <sc>. It was originally pronounced [sk], but in time the two consonants merged into the consonant [∫]. This sound change did not happen in ON, so in the following sample of words, it is the OE pronunciation that MnE reflexes have kept.

|

OE |

ON |

MnE |

|

Sceaft |

Skapt |

Shaft |

|

Scell |

Skell |

Shell |

|

Scearp |

Skarpr |

sharp |

|

Scinan |

Skina |

Shine |

|

Scield |

Skjoldr |

Shield |

|

Scufan |

Skufa |

Shove |

|

Fisc |

Fiskr |

Fish |

![]()

Going ahead through history we arrive to the French invasion and its consequences on the language. We can observe the French spelling conventions.

![]() <ch> replaces

OE <c> for [t∫], and <k> or <ck> for [k]. For example, the OE word “macode”

is now spelt “makede”.

<ch> replaces

OE <c> for [t∫], and <k> or <ck> for [k]. For example, the OE word “macode”

is now spelt “makede”.

![]() <qu> replaces

OE <cw>. For example: cwene is now quene.

<qu> replaces

OE <cw>. For example: cwene is now quene.

![]() Now the letter <g> is introduced.

Now the letter <g> is introduced.

![]() There are variant spellings for [∫].

The digraph <sc> was pronounced [sk] in early OE, but

changed to [∫]. The influence of Old Norse words with <sk> led to a spelling

change, with several letters or digraphs for [∫].

There are variant spellings for [∫].

The digraph <sc> was pronounced [sk] in early OE, but

changed to [∫]. The influence of Old Norse words with <sk> led to a spelling

change, with several letters or digraphs for [∫].

o <sc> became rare after the 12th century.

o <s> was used in the 12th and 13th centuries initially and finally.

o <ss> was more frequent than <s> in all positions.

o <sch> was the commonest form from the end of the 12th century to the end of the 14th century.

o <ssh> was the common form the 13th to the 16th century in medial and final positions.

o <sh> is regularly used in the Ormulum.

![]() <gg>

replaces <c¯>.

For example:

sec¯e

became segge.

<gg>

replaces <c¯>.

For example:

sec¯e

became segge.

As we have seen in the OE the consonants change its form and spelling. So in this period we are going to observe some of them. First, the loss of the initial [h] and then [γ] to [h] or elision of [γ].

The loss of the initial [h]

Word-initial <h> was not pronounced in French, and the borrowing of numbers of French words beginning with <h> has led to its regular pronunciation in present-day English. There are three possibilities in MnE:

![]() A few borrowed French words have lost initial

<h> in both spelling and pronunciation, like able.

A few borrowed French words have lost initial

<h> in both spelling and pronunciation, like able.

![]() A few others are spelt with an initial <h>

which is not pronounced, like heir, hour, honest, honour.

A few others are spelt with an initial <h>

which is not pronounced, like heir, hour, honest, honour.

![]() In most cases, the <h> is now pronounced in RP

“spelling-pronunciation” having been adopted – harmony, herb, heredity,

hospital and so on, and in England there is divided usage over hotel -

[əhəυtεl] v. [əυtεl].

In most cases, the <h> is now pronounced in RP

“spelling-pronunciation” having been adopted – harmony, herb, heredity,

hospital and so on, and in England there is divided usage over hotel -

[əhəυtεl] v. [əυtεl].

[γ] To [h] or elision of [γ]

The spelling <h> for /h/ may or may not represent a change from the velar fricative [γ] to the glottal fricative [h]. The fact that the same word is spelt both brouhte and broute presents a problem that we cannot solve without more evidence.

The change of [m] to [n] in unstressed suffixes is part of the general reduction and final loss of most inflections. For example <-am> -à <-an> þam / þan = the

<k> from ON and <ch> from OE

The contrast here comes from the Northern use of words derived from ON, or from Northern pronunciation with [k] of OE words with [t∫]:

Rike/riche ON rikr/OE rice and OF riche

Like/liche and ilic/I liche ON likr/OE (GE)lice

Suilk/suche Northern form of OE swilc, swelc

<qu-> for <wh->

This <qu-> spelling is not the French convention for the spelling of OE <cw> but a representation of a heavily aspirated fricative consonant, [hw]; (qu-) or (quh-) was in fact retained in Scots spelling through to the 17th century:

Quam/--- (= whom) quat/what

<gh>

In OE, letter yogh <¯> had come to represent three sounds - [g] [j] and [x] With the adoption of the continental letter <g> for [g], <¯> tended to be used for [j]. Two related sounds that occurred after a vowel, [ç] and [x], caused problems of spelling, and among different choices, <gh> became common; [ç] and [x] are fricative consonants:

Faght/fau¯t right/ri¯t

The sounds [x] and [ç] were eventually elided in many words, e.g. brought, sought, right, bough (though the spelling has been retained). In others it became the fricative consonant [f], as in cough, tough, enough. The irregularity of the MnE pronunciation of <gh> is the result of a fairly random choice between different dialectal pronunciations:

þof/ þou¯e

Diversity of pronouns

3rd person singular feminine pronoun (MnE she)

The variant forms for she are the evidence for different evolutions in different areas. Both the initial consonant and the vowel varied. In the Southern and West Midlands dialects the inicial [h] of OE heo was retained, but with a variety of vowel modifications and spellings illustrated in the first group of quotations below.

The form scho with initial [∫] and vowel [o] developed in the Northern dialect, and probable evolved from the feminine personal pronoun heo, perhaps influenced also by the initial consonant of the feminine demonstrative pronoun seo .

In the East Midlands dialect the origin of the form sche, with inicial [∫] and vowel [e], which became the standard she, is not known.

Ambiguity of ME in different dialects

The asimilation of the ON plural pronouns beginning with <th>.

Where there was a large Scandinavian population, in the North, all three forms they, them and their replaced the older OE pronouns beginning with (h). In the South, the OE forms remained for much longer. In the Midlands, they was used, but still with the object and possessive pronouns hem and hire.

Spelling and pronunciation in the South

<¯> used for [x] ber¯e (protect)

<y> is dotted <ỷ> and used for [ı] ỷcome and for [j] manỷere

<g> for [g]: god, engliss.

Thorn <þ> still used: þe, þet.

<w> used in all cases, never wynn <ρ>: wille, ywent.

Word-initial <z> and <u> for voiced fricatives [z] and [v]: zende (send), uor (for).

Kentish was a conservative dialect - that is, when we compared with others it still retained more features of the OE system of inflections, even though greatly reduced. These features are very similar to those of South-Western texts.This fact is not surprising when we consider the geographical position of Kent, relatively cut off and distant from the Midlands and North of England, but accesible to the rest of the world.

The consonants pronounced [f] and [s] in other dialects were voiced at the beginning of a word or root syllable in Kentish, and pronounced [v] and [z]. The inicial voicing of fricative consonants is still a feature of South-Eastern dialects. It applies equally to the consonant [q], and must have done also in ME, but has never been recorded in spelling, because the letters <þ> or <th> are used for both the voiced and voiceless forms of the consonant.

South-Western dialects

Spelling and pronunciation

Letter thorn written like <Þ>

Letter <w> used, not wynn

The 2-form of <r> after <o>

Letter yogh <¯> used for [j] ¯onge, [x] fi¯te and [tz] fi¯ (Fitz).

<y> - is interchangeable with (i), and represents the sound [Ι]: bygynnyng.

<u> and <v> - the familiar present-day relationship of letter <u> for vowel [u] and letter <v> for consonant [v] is still not established; <u> and <v> were variant shapes of the same letter.

<¯> and <g> - yogh, <¯>, is retained for [j], [x] or [�]. The letter (g) represents both [g], and also [¯] in borrowed French words like usage [uza¯].

<ch> - replaced OE <c> for the sound [t∫]: speche, teche.

<sch> - is Trevisa´s spelling for OE <sc>, [∫] englysch, oplondysch.

<th> - has not repaced (þ) in Trevisa.

Northern dialects

Spelling and pronunciation

<¯h> - is written for <¯>, representing the consonant [j]: fail¯he [faılj].

<ch> - is written for the <¯> or <gh> used in other dialect areas for the sound [x], as well as for the [t∫] in wrechyt.

<ff> - the doubled letters indicate unvoiced final consonants as in haiff and gyff.

<y> - from OE <þ>, is used for <th> in some funtion words, as well as an alternative for <i>.

MODERN ENGLISH

DEVELOPMENTS OF THE CONSONANTIC SYSTEM DURING MODERN ENGLISH.

During the period of Modern English non-greater changes occurred, in contrast with the ‘evolution’ from Old English to Middle English.

1. Regular Evolution

MIDDLE ENGLISH MODERN ENGLISH EX.

/p/ /p/ Paþ / Path/ Path

/t/ /t/ Tunge/Tonge/Tongue

/k/ /k/ Kū/Cōu/Cow

/b/ /b/ Bēde(n)/Bid

/d/ /d/ Dæi/Dai/Day

/g/ /g/ Goos/Goose

/ tʃ/ / tʃ/ Chōse(n)/Chēse(n)/Cose

/dʒ/ /dʒ/ Brigge/Brugge/Bridge

/f/ /f/ Fāder/Father

/s/ /s/ Sende(n)/Send

/θ/ /θ / Paþ/Path

/v/ /v/ Vinagre/Vinegar

/z/ /z/ Nōse/Noyse/Nose

/ð/ /ð/ þe/The/The

/ʃ/ /ʃ/ Sheld/Sheld(e)/Shield

/h/ /h/ Hūs/Hōuse/Hōws/House

/m/ /m/ Mōne/Moon/Moon

/n/ /n/ Nāme/Nayme/Name

/ŋ/ /ŋ/ Synge(n)/Singin/Sing

/l/ /l/ Leye(n)/Lay

/r/ /r/ Rēd(e)/Reed/Red

/w/ /w/ Wey(e)/Wei/Way

/j/ /j/ ¯eong/Yong/Yunge/Young

2. Consonant changes during Modern English.

A. SPECIFIC CHANGES

- /ŋ/ like allophone of [n] before [k] or [g], but later [g] disappear in the group [ŋ g] at the end and [ŋ] acquired phonetic value .

- /ʒ/ (XVII century) is the result of the combination of [zj] in middle position that is not marked. It can be contrasted with its voiceless equivalent /ʃ/.

- /ʒ/ This form was increased when it adapted in final position for the French loanwords: beige, garage, rouge…

- [d]>[ð] between vocal and syllabic “r” ([r] or [ər]) (mōder/mooder/mother; weder/weather…)

- There is a phonetic change of nature of [r], falling in some dialects after [ə] or long vowels.

- [t]>[r] potage>porridge

- [s] and [t]>[ʃ] in words such as passion or nation.

B. THE PROCESSES CONTINUE

1. Voicing

[f]>[v], [θ]>[ ð], [s]>[z]

Since the primitive Germanic, fricatives were voiced between voiced elements in middle position, but phoneticians, in the beginnings of Modern English found alternations between voiced and unvoiced:

Nephew: [nevju(:) ] and [nefju]

In Modern English, voicing is extended to initial position: it is clearly showed in the orthographies “f/v” and “s/z” and without orthographic evidence in the case of [θ]; but without reaching out to crystallize in Modern English.

In the XIV century (Middle English) begins the tendency to voicing of fricatives in final position non marked if the next element was voiced:

Pensif>pensive

2. Simplification of consonants

- Final [b] falls in the group [mb]: lamb, dumb… (by analogy it is introduce a final “ b” in the words that hadn’t any: lim>limb)

- [d] falls in the group [nd]: ex. Thousand, always that the word isn’t followed by a syllabic consonant: bundle

- [g] Falls after the apparition of a new phoneme [ŋ] and falls in the group [gn] too: gnat, gnash…

- [l] falls between [a:], [o:], [ou] and [k],[f], [v], [m], [p], [b]: talk, half, halve, alms, folk, Holborn…

- Final [n] falls preceding [m]: condemn. And sometimes in precedence of [l]: miln>mill.

- [t] began to fall in the groups [stl], [stm], [stn]: Castle, Christmas, listen…

CONCLUSION

As we have stated throught this work, major changes in the consonant system occured in the transitional period from OE to ME, whereas most changes from ME to MnE were basically in spelling rather than in pronunciation. Here follows a table showing the evolution of the consonants taking the phonemes as a starting point and then a contrast between their different spellings across time.

|

Phoneme |

OE |

ME |

EMnE |

PdE |

|

/b/ |

b |

b, bb |

b, bb |

b, bb |

|

/k/ |

c, k (rare) |

k, kk, c, cc, qu (for /kw/) |

k, kk, c, cc, ck, qu (for /kw/ or /k/), ch (in loanwords) |

k, kk, c, cc, ck, qu (for /kw/ or /k/), ch (in loanwords) |

|

/t∫/ |

c |

ch, cch |

ch, t, c, cch, tch |

ch, t, c, tch |

|

/d¯/ |

c¯ |

cg, c¯ (rare), ¯¯ (rare), gg, j, ig, ¯ |

dg, dge, j, d, g |

dg, dge, j, d, g |

|

/s/ |

s |

s, ss, c |

s, ss, c, t |

s, ss, c |

|

/d/ |

d |

d, dd |

d, dd, ed |

d, dd, ed |

|

/t/ |

t |

t, tt |

t, tt, d, ed, et |

t, tt, d, ed, et |

|

/f/ |

f |

f, ff |

f, ff, ph |

f, ff, gh, ph |

|

/v/ |

f, v |

v, u |

v, u, vv, uu |

v |

|

/g/ |

¯, g (rare) |

¯, g, gg, gh |

g, gg, gh |

g, gg, gh |

|

/j/ |

¯, g |

¯, g, y, i (rare) |

y, i (rare) |

y, u (to represent /j/ + /u/) |

|

/h/ |

h |

h |

h |

h |

|

/n/ |

n |

n, nn, gn |

n, nn, gn |

n, nn, gn |

|

/¯/ |

- |

- |

z, s, si, g |

z, s, si, g |

|

/l/ |

l |

l, ll |

l, ll |

l, ll |

|

/m/ |

m |

m, mm |

m, mm, mn |

m, mm, mn |

|

/?/ |

- |

- |

ng |

ng |

|

/p/ |

p |

p, pp |

p, pp |

p, pp |

|

/r/ |

r |

r, rr |

r, rr |

r, rr |

|

/z/ |

- |

s, z, zz, ¯ (rare) |

s, z, zz |

s, z, zz |

|

/?/ |

þ, ? |

?, þ, th, y |

th, þ, y |

th |

|

/θ/ |

þ, ? |

þ, ?, th, y |

th, þ, y |

th |

|

/w/ |

w |

w, wh, qu |

w, wh |

w, wh |

|

/∫/ |

sc |

sc, sh, ssh, sch, ss |

s, sh, c, ti, ss, sch (loanwords), si, ssi |

s, sh, c, ti, sch (loanwords), si, ssi |

|

/γ/ |

¯, h |

- |

- |

- |

|

/ç/ |

h |

- |

- |

- |

|

/x/ |

h |

- |

- |

- |

As we can appreciate, in OE most sounds corresponded to a single grapheme or vice-versa, whereas the number of graphemes was considerably increased during the period of ME, especially in the 13th and 14th centuries, though a few sounds were lost (/γ/, /ç/, /x/).

In EMnE two new sounds appeared (/¯/, /?/) and a few symbols were no longer in use (¯, þ, ?). The number of graphemes to represent sounds was more or less stable.

Finally, it must be said that phonological and ortographical variations concerning consonants have not been significant in the last 400 years (from EMnE to PdE), and most of them have dealt with and led to simplification.

History of English Language 2006-2007:

Victoria Grau

Laura Navarro

Amparo Garcés

Rubén Balaguer

References:

-Dennis Freeborn: From Old English to Standard English.

-N. F. Blake: A History of the English Language.

-Internet website: facweb.furman.edu/~wrogers/phonemes/