Heart

of Darkness & Apocalypse Now:

Heart

of Darkness & Apocalypse Now:

A comparative analysis of novella and film

In the opening scenes of the documentary film "Hearts of Darkness-A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," Eleanor Coppola describes her husband Francis's film, "Apocalypse Now," as being "loosely based" on Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Indeed, "loosely" is the word; the period, setting, and circumstances of the film are totally different from those of the novella. The question, therefore, is whether any of Conrad's classic story of savagery and madness is extant in its cinematic reworking. It is this question that I shall attempt to address in this brief monograph by looking more closely at various aspects of character, plot, and theme in each respective work.

The story of Heart of Darkness is narrated by its central character, the seasoned mariner Marlowe, a recurring figure in Conrad's work. "Apocalypse Now" features a corollary to Marlowe in Captain Willard, a U.S. Army special forces operative assigned to go up the Nung river from Viet Nam into Cambodia in order to "terminate the command" of one Colonel Walter Kurtz whom, he is told, has gone totally insane. It is fitting that Marlowe's character should be renamed, as Willard differs from Marlowe in several significant ways: 1) He is not the captain of the boat which takes him and a party of others up the river; 2) He does not reflect the deep psychological and philosophical insights that are a signal feature in Marlowe's character, and 3) He is sent on his mission specifically to kill Kurtz, unlike Marlowe who is simply piloting others in the capacity of captain of a steamboat. However, Willard does communicate Marlowe's fascination (growing, in fact, into an obsession) with Kurtz. Also significant is the fact that he holds the rank of captain, tying in with Marlowe's occupation.

As to the character of Kurtz, it is worth noting that while significant discrepancies exist between the depictions of Conrad and Coppola, the basic nature of the man remains fairly similar. The idea of company man turned savage, of a brilliant and successful team-player, being groomed by "the Company" for greater things, suddenly gone native, is perfectly realized in both novella and film. In the film, Kurtz is portrayed by Marlon Brando, the father of American method actors, who lends weight (both physically and dramatically) to the figure of the megalomaniacal Kurtz. Brando's massive girth is all the more ironic for those familiar with Heart of Darkness who recall Conrad's description: "I could see the cage of his ribs all astir, the bones of his arms waving. It was as though an animated image of death carved out of old ivory had been shaking its hand with menaces at a motionless crowd of men..." [1]. One could speculate that Coppola's Kurtz is a graphic analogy of the bloated American war machine dominating and perverting the innocent montegnards of Cambodia; however, after viewing Eleanor Coppola's documentary, one finds that the casting was more based on a combination of Coppola's wanting to work with Brando (remember "The Godfather") and Brando's own weight problem.

Heart of Darkness is brilliantly and subtly updated by Coppola in a foreshadowing scene in which missives to Willard from headquarters are intercut with scenes of newspaper clippings about Charles Manson.)

Also present in Coppola's film is the loveable, addle-headed harlequin/fool figure who meets Marlowe's boat upon arrival at Kurtz's station. This role is rendered in grand, demented style by Dennis Hopper, replete with a plethora of cameras (he is an American photojournalist) to update his fool's motley. Much of his dialogue is taken directly from Conrad, although his character does not flee the scene as does his doppelganger in Heart of Darkness.

Regarding plot, as stated earlier, Coppola's rendering of Heart of Darkness diverges wildly from Conrad. Conrad's story depicts a turn of the century riverboat captain transporting members of an unnamed "Company," an ivory trading concern, up a snake-like river winding its way into the Belgian Congo in order to locate their top "agent" and relieve him of his independently-stockpiled ivory. The Company has judged Kurtz to be a renegade whose methods are "unsound." Coppola's film gives us Willard, an Army captain who is sent by Army intelligence up a similar river in Viet Nam to kill a certain Colonel Kurtz. Again, Colonel Kurtz is considered by the parties in charge to be insane, his methods unsound (a direct dialogue echo from the text.) This last fact, however, that Willard is from the beginning an assassin, is a fundamental difference between the film and the book. It changes the whole psychological dynamic between that of Marlowe and Kurtz. In Conrad, Marlowe is in awe of Kurtz, comes to identify with him in some dark recess of his own psyche; Willard, on the other hand, is more impressed with Kurtz's credentials than moved by his force of mind and will. His mission to kill Kurtz gives him some measure of pause, but his military protocol mentality ultimately rules the day. Compared with Marlowe's deep, searching ruminations on the dark, enigmatic Kurtz, Willard is a government-issue automaton. Add to this the fact that the first two thirds of the movie "Apocalypse Now" are concerned with the Viet Nam war and have absolutely nothing to do with the plot of Heart of Darkness, and it seems as if there is an unmendable rift between the film and its purported inspiration. To be fair, however, it is important to mention that the two plots do converge at the point just before the boat parties arrive at Kurtz's station, when a thick fog envelops each boat and a rain of arrows showers down on the passengers. From here we witness the death of the black helmsman by a spear, the greeting of the fool figure, and, finally the meeting with the mad Kurtz.

Which brings us to the question of theme. The dominant theme of Heart of Darkness is man's vulnerability to his own darker nature and the various ways in which this terrible, savage, proto-man can be unleashed; power, the jungle, "the Company," all serve as catalysts for the emergence of this hidden, voracious id-thing within us all, most realized in Kurtz. In "Apocalypse Now," Coppola is right on target in exploring this theme, his choice of Viet Nam in the sixties providing all the requisite elements: power, the jungle, and "the Company" are all present, the latter being represented by the U.S. Army, or perhaps the U.S.A. as a whole. This last touch is ingenious, as it calls up a whole series of speculations regarding the various forms of imperialism. In Conrad, set at the turn of the century, the imperialism is traditional, overt. In Coppola, the U.S. presence is just as overt, yet the pretense upon which it is based is more ideological, geopolitical. Both situations provide the possibility for endless abuse of power by foreigners in a primitive jungle setting, a setting which tends to bend their minds and release their dormant savage energies. Heart of Darkness depicts gun-crazy members of "the Company" firing wildly upon anything and everything as they progress up the river. Likewise the men in the PBR in "Apocalypse Now," even more so, in fact, due to the circumstances of the Viet Nam war.

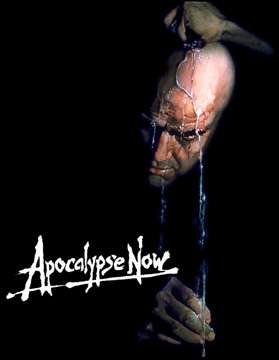

The ultimate extreme of man's dark side, as explored in Conrad and Coppola, is madness. The embodiment of this madness is Kurtz, and it is explored more thoroughly, in fact, in Coppola. One might argue that no credit is to be given to Coppola for this, that so many men went mad in Viet Nam, that the war was madness itself. But the way in which Kurtz's madness is portrayed must be examined: the way Brando is filmed in perpetual half-shadow, as if darkness is pouring over him in some black ooze; the strange, nonsensical yet at the same time compelling ruminations he shares with Willard; the scene in which he beheads one of Willard's men and presents the trophy to Willard in full camouflage make-up. These are examples of the filmmaker's craft and should not be overlooked.

To sum up, the question must be answered as to whether Conrad's Heart of Darkness has survived the passage of seventy-five years and a cinematic treatment by Francis Ford Coppola. I would say yes, in its basic thematic elements, it has. Much has changed, but the basic feel of the novella, the brooding, mysterious jungle energy, its maddening influence over those who would try to tame it, and Kurtz, whose soul went mad, whose last words were "The horror, the horror," all remain relatively in tact. I wonder what Conrad would have thought.

|

Apocalypse Now

|

|---|