Navigation:

The Importance of Adriana

in The Comedy of Errors

Family Life in some Shakespearean

plays

Shakespeare on Film

(collective paper)

SHAKESPEARE ON FILM

Collective Paper by:

INDEX

Evolution of cinema and

Shakespearean adaptations

Four examples of Shakespearean

adaptations

A Midsummer Night's Dream

(1999)

10 Things I Hate About You

(1999)

In some sectors of the academic field there seems to be a quite extended prejudice against films that are adapted in some way or another from a literary piece of work. It gets much worse if we are talking about adaptations that are apparently unfaithful. Many scholars seem to consider that any revision or update of a classic text tears out part of its originality. Shakespeare is probably the classic author with more works adapted to the screen and that prejudice I mentioned before can be applied to his plays.

A quick search on the Internet about this issue offers us some strong opinions against Shakespearean film adaptations and intense (and also interesting) arguments. A good example of this can be found in Shaksper [1] , an online mailing list for academic discussions on Shakespeare and his plays. We can find there the article “Towards a New Dunciad” [2] , where Charles Weinstein wonders about the legitimacy of what he calls a “pseudo-discipline” in four different points. Weinstein himself summarizes his harsh article in just two sentences: “The plays are masterpieces; the films are not” therefore “these movies aren't good enough or important enough to be the subject of an academic discipline”. Of course, Weinstein is forgetting that plays are meant to be performed, which means that each performance is a revision of the original text in itself… just like films.

Maybe it is true that not all of Shakespeare’s plays adaptations are worthy of being analysed (porn adaptations [3] such as A Midsummer Night’s Cream, Taming of the Screw or As You Lick It are probably not), but the important question is if these cinema versions are able to transmit Shakespeare’s works (his plots, his themes, the richness of his characters, his humour…) to the audiences of the historical moment in which they are produced. Faithful “word by word” adaptations may be well-regarded by literary critics, but they would be a complete failure if they cannot be understood (or enjoyed) by the majority of the public. Our purpose is to answer that question through the study of the development of cinema in the last century and, at the same time, the constant evolution of Shakespearean adaptations to meet with the expectations of different audiences. The first part of this paper will deal mainly with those parallel evolutions.

For the second part, as we did in our previous paper, we have chosen several film versions of plays by Shakespeare to analyse them. However, this time we are going to focus in their cinematographic qualities (use of the camera, lighting, special effects, sound effects, music, the casting of actors…) to link with our description of the history and development of cinema.

EVOLUTION OF CINEMA AND

SHAKESPEAREAN ADAPTATIONS

Silent films

Although there were earlier experiments [4] concerning the movement of images and optical effects, there is an unspoken agreement to establish the beginning of cinema in the late 1890s, with the invention of the Cinématographe by the Lumière brothers. The first films only showed a single and short scene and most of them were records of real life events. Little by little, the scenes began to grow and to be divided into several actions and some fiction stories and performances were recorded. The figure of the French film director Georges Méliès [5] is one of the most important in the history of early film-making. He founded one of the first film studios and created more than five hundred films in which he applied innovative techniques.

A photograph of King John’s 1899 adaptation included in A History of Shakespeare on Screen

The second appearance of a Shakespearean film starred the actress Sarah Bernhardt [10] as Hamlet in Le Duel d’Hamlet (1900), a short scene that showed the famous duel between Hamlet and Laertes in the final act of the play. The film was first played in the Exposition Universelle of Paris and it was not really a silent movie because it had dubbed dialogues and even sound effects. In fact, it is probably the first film that had a synchronized soundtrack. We have to keep in mind that these early examples of films based on Shakespeare were just recordings of theatrical performances. There was a single and static camera, recording what happened on stage, nothing else.

Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet

From that point onwards, film directors (especially French and Italian) created many different film versions of Shakespeare’s works. During the first three decades of the 20th century, around 150.000 silent movies were produced and Rothwell states that about 500 of them were based on Shakespeare’s works in one way or another. These were also the years in which the United States started to surpass old Europe in terms of economy and, as a consequence, culture. American Vitagraph Studios, founded by Blackton and Smith in Manhattan in 1897, were responsible of the first overseas adaptations of Shakespeare (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Anthony and Cleopatra, As You Like It, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Merchant of Venice, Othello, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, and Twelfth Night), all of them produced between 1908 and 1912. These films started to offer a different view on Shakespearean film. They were no longer a recorded theatrical performance, that is, there were shots taken from different points and distances, especially in their version of Romeo and Juliet. They also included different real locations to record some outdoors scenes, like the duel between Romeo and Tybalt, filmed in Central park.

In the late 1920s, the silent films were at its summit. Every aspect of silent film-making and acting had been polished and refined, but then the sound era started and changed drastically the history of cinema. Silent movies became obsolete in less than two years.

As everybody knows, The Jazz Singer (1927) is considered the first sound film ever. There were previous experiments with sounds, as we mentioned when talking about Le Duel d’Hamlet, but The Jazz Singer was the first film to include completely synchronized dialogues and singing. Two years after that, silent films had disappeared in the United States. According to Michael LoMonico, that swift transition from silent movies to sound movies can be seen in The Taming of the Shrew1929’s version, played by Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. This adaptation was filmed as a silent movie, and dialogues had to be added later. The tagline of the film is pretty significant: “All Talking! All Laughing!”

These first years of sound cinema represented a step back in terms of creativity and professionalism. Actors and directors from the silent film era had a rough time trying to adapt to the new format and the same happened to technicians. Theatre directors and actors began to work for the film studios, as both of them had more experience in stories that included dialogues.

The next two decades, from 1930 to 1950 approximately, are considered the Golden Age of Hollywood. Many genres started to develop, and others were born during these years (musical films, for instance), colour film [11] was gradually introduced in the industry, and what is more important: the first real film stars appeared and with them, Hollywood’s glamour. Several Shakespearean films were recorded both in the United States and England, but according to Jackson [12] they were not an economic success:

None of the first wave of Shakespearean sound films was a financial success. The 1935 Warner Brothers’ A Midsummer Night’s Dream was announced as inaugurating a series to be made with its distinguished co-director, Max Reinhardt, but after its failure at the box-office nothing came of these plans. The opulent Romeo and Juliet directed by George Cukor and produced by Irving Thalberg at MGM was an expensive showcase for Thalberg’s wife, Norma Shearer. Paul Czinner’s British production of As You Like It […] was no more of a success, for all its lavish production values.

Zeffirelli’s

The Taming of the Shrew

Something was wrong with these film adaptations. They were not able to catch the public’s attention or interest. Jackson states that we had to wait until the late 60s, with Zeffirelli’s The Taming of the Shrew (1966) and Romeo and Juliet (1968) to have another Shakespearean play successfully adapted to the big screen both artistically and financially. Jackson surprisingly omits the musical West Side Story (1961), that is clearly inspired in Romeo and Juliet and that won ten Oscar awards. In any case, Zeffirelli’s films managed to connect with their contemporary audiences offering less classic versions of the original texts and emphasizing those aspects and themes that are traditionally popular such as love or humour. Robert Hapgood, in his article “Popularizing Shakespeare: The Artistry of Franco Zeffirelli” [13] explains the success of Zeffirelli’s Shakespearean films (the two mentioned before plus 1990’s Hamlet) with a self-explanatory quotation of the Italian director: “I have always felt sure I could break the myth that Shakespeare on stage and screen is only an exercise for the intellectual. I want his plays to be enjoyed by ordinary people.” This declaration of intention probably holds the key as to why Zeffirelli’s films were successful and those before him weren’t. Zeffirelli, just like Shakespeare four centuries ago, made artistic products that could be enjoyed by everybody, perhaps other directors were not aware of who their real audience was.

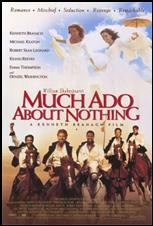

In the years of the videotapes and the blockbusters, Kenneth Branagh is probably the most important figure of Shakespearean films. He started his career as a director with Henry V (1989), wisely combining cinematographic techniques (such as flashbacks) and theatrical ones (the classical chorus). Russell Jackson states that the humble budget of the film and its great success “appears to have inaugurated a new wave of confidence in Shakespearean projects”. Branagh himself directed Much Ado About Nothing in 1993 (another one of the films we are going to analyse in this paper) which was also well-considered by the critics.

His next project, however, could be considered a little failure in

financial terms. In 1996 he adapted Hamlet word by word, filming a 238

minutes film that made it to the cinemas in a quite shortened version. The

reviews were really good. The adaptation respected the original text and,

at the same time, updated some of its

Kenneth Branagh as Hamlet elements; the action was set in the 20th century and the luminosity

of the locations contrasted with the black clothes of the prince of Denmark;

important figures of cinema and theatre such as Charlton Heston, Jack Lemmon,

Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie or Judi Dench appeared in the credits. Perhaps

the

elements; the action was set in the 20th century and the luminosity

of the locations contrasted with the black clothes of the prince of Denmark;

important figures of cinema and theatre such as Charlton Heston, Jack Lemmon,

Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie or Judi Dench appeared in the credits. Perhaps

the

only mistake was to make a film only for those

who admire the original text. In Love’s Labour’s Lost (2000) the Belfast director tried to innovate again and this time he used

the musical genre to retell Shakespeare’s light-hearted story. Branagh’s latest

approach to Shakespeare is the adaptation of As You Like It, not yet released in Spain.

In the last years most of Shakespearean film adaptations have followed

the same tendency: updating the stories to a contemporary setting and adding

current themes. Almost at the same time that Branagh’s Hamlet was premiered, we got another adaptation of a Shakespeare play: Romeo

and Juliet. Baz Luhrmann took the action to the streets of

Verona Beach, in Los Angeles, where a Romeo played by teen star Leonardo DiCaprio

tried to get Juliet’s (Claire Danes) love. The film was fast-paced, just like

a musical video clip and offered a shocking modern aesthetic than some disliked,

but the truth is that it was really successful. Both Luhrmann and DiCaprio

were awarded at the Berlin International Film Festival, and Claire Danes got

several prizes such as the Actress of the Year at the London Critics Circle

Film Awards. Luhrmann succeeded in addressing a particular audience (teenagers

and young people mainly) and creating a film just for them, using narrative

codes that they could understand and at the same time respecting the core

of the story: love and tragedy.

In a similar way, the last version of Hamlet (2000), directed by Michael Almereyda takes the tragedy of the prince of Denmark (played by Ethan Hawke) to nowadays’ New York. Another example would be O (2001), known in Spain as Laberinto envenenado, which is a revision of Othello’s story set in an American Boarding School where a black student (Mekhi Phifer), the star of the basketball team, falls in love with a white girl (Julia Stiles) and is fooled by one of his team-mates’ treachery (Josh Hartnett).

We cannot forget the adaptations of Shakespeare’s works created in non-western cultures. Ran (1985) and Throne of Blood (1957) by Akira Kurosawa are probably the best-known, but film adaptations of Shakespearean plays have been very common in Bombay’s Bollywood: Omkara (2006) and Maqbool (2003) by Vishal Bharadwaj, based on Othello and Macbeth, are good examples.

Probably the best explanation of this phenomenon is the one offered by the Indian director [14] : “Shakespeare is universal because he deals with ordinary human emotions: jealousy, anger, love, envy. His story can be adapted across any language, country or culture. The backdrop is redundant.”

FOUR EXAMPLES OF SHAKESPEAREAN

ADAPTATIONS

Much Ado About Nothing (1993)

Plot

and structure

Plot

and structure

Shakespeare's universality of themes are timeless and therefore, his adaptations into cinema have been translated into perfection when put on to screen. In Much Ado About Nothing, which will be the first of our comparisons, Kenneth Branagh portrays two young lovers, Hero and Claudio who are to be married in one week. This wedding is intended to be broken up by Don John who conspires against Hero accusing her of infidelity. As it can be seen, no feeling is more everlasting than love and no pain is such than two lovers unjustly separated, what causes Shakespeare’s plays to have an inherent cinematic outcome. Meanwhile, Don Pedro of Aragon will try to set a “lover’s trap” for Benedick and Beatrice, both characters who stand out as sceptic, arrogant and who proclaim will never become “fools for love”.

Kenneth Branagh’s adaptation of this play was produced in 1993 and while William Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing is set in Messina, an island of Sicily, Branagh’s film version is set in Villa Vignamaggio, Chianti, a region of Tuscany (rather than a city). Both settings convey Shakespeare’s intention of escapism in that they are placed in a foreign country in order to create the sensation that the problems within the text were also foreign to Elizabethan society. When watching the film adaptation, one must take into account that the order of certain scenes has changed, the dialogue is edited and many scenes are intercut. The reason for this is obvious: Shakespearian themes are universal but audiences slightly change with time, and consequently, directors must adapt Shakespearian plays into thematically lighter films which have a faster speed and with a more entertaining succession of events.

Concerning structure, Shakespeare’s play follows the classical unities of place (one single location), time (brevity of events) and action (one main story with sub-plots). As the comedy it is, it deals with the struggle of young lovers overcoming problems and confusions which are gradually resolved with a happy ending. One of the differences which makes Branagh’s version more light-hearted than Shakespeare’s is that the director minimizes the tragic aspects of the play. These tragic aspects prove to have been undermined basically because less stress or focus is paid to Hero and Claudio’s stormy relationship, and therefore less sadness and uncertainty exists to contrast the happy ending.

In addition, Much Ado About Nothing, having to be shaped into a popular film and despite Branagh’s loyalty in adaptation to the original script, phrases which are purely ornate language are erased, mainly to speed the action of the film and probably because they could be incomprehensible for today’s general public and phrases which would sound offensive to contemporary audience are also erased.

Characters

At the time the film was produced, cinema was a business and having famous people enabled the director attracting a massive audience. This leads Kenneth Branagh to choose well-known actors, such as: Emma Thompson as Beatrice, Denzel Washington as Don Pedro of Aragon, Keanu Reeves as Don John, Michael Keaton as Dogberry and he himself as Benedick. Although the director has neither add nor omit any character from the original version, he represents some of them differently from Shakespeare’s original portrait:

Claudio is seen as an emotional and sensitive character in the film. His voice shakes when he is refusing Hero in their wedding and he is unable to speak when he discovers Hero alive, being capable only of kissing her hand. In the text, Claudio is portrayed as a heroic and brave man, proud of his victorious actions in war and there is a hint to superficiality in that economic reasons prevail in their marriage, while in the film these are omitted. This change in Claudio’s behaviour, his personality and the way he speaks and acts gains the audience’s sympathy towards him against Don John, who wants Hero for him.

Branagh represents Don John as a villain. Whilst Shakespeare relied on portraying Don Pedro’s bastard brother through his words (i.e. with language as his only tool), making a verbal sensuality, Branagh is allowed to use visual effects, as is commented later, including music and different atmospheres. Whilst almost the whole film is placed outdoors, Don John is always placed in the underworld, surrounded by torch-lighted and sinister places. His setting emphasizes his bad intentions: whilst the other characters are enjoying the masked ball outdoors, Don John is seen running through a dark corridor laughing fiendishly. Kenneth Branagh links Don John attitude with darkness and obscurity in the villa, which helps him to create an image of a jealous and despicable villain inhabiting an underground world of evil and malevolence.

Another change in the portrayal is found in Dogberry, who is represented as loony and mad in Branagh’s version, pretending to ride a horse and using malapropisms, whilst in the original version Shakespeare represents him as slow-witted, ignorant and stupid.

The character of Benedick is related to another fact to remark about changes in characters. For example, whilst in William Shakespeare’s play Benedict is overtly blunt in his racist commentaries, which in Elizabethan times would probably be accepted, in the adaptation of the film, Branagh removes phrases such as “If I do not love her, I am a Jew” (II,iii,101) or “I'll hold my mind were she an Ethiope” (V,iv,2585) from Benedick’s mouth, basically because nowadays, these would sound offensive to a contemporary audience: for instance statements which may be regarded as old-fashioned are removed not to provoke a bad reaction of the audience against the character.

The most surprising character in the film is Don Pedro of Aragon. Branagh’s choice of Denzel Washington, a coloured man, for this character helps to reinforce the escapism in the setting: having a black-skinned character makes the audience feel the remoteness of the location of the play.

Cinematographic

techniques

In the film industry, the cinematographer is responsible for the technical aspects of the images but works closely to ensure that the artistic aesthetics are supporting the original version of the story being told[15]. Kenneth Branagh attempts to be loyal in his interpretation of Shakespeare’s play and through the use of sound effects, music and an intentional predisposition of taking different shots, he is able to add to the general meaning and essence of Shakespeare his own subtle interpretation. With the use of new technologies he not only slightly changes the general mood, but also changes the audience’s perception or reaction, by adding, omitting or even fastening events.

According to the website www.filmeducation.org, “the opening sequence of a film, like the opening scenes of a play, must catch the audience’s attention and engage their interest, making them eager to know what happens in the rest of the story. It must also set the scene for where the action is to take place, give clues as to the major characters and indicate what type of story we are about to hear and see”.

In Much Ado about Nothing, Kenneth Branagh takes it into account, starting his film with a bucolic image which engages audience’s interest. It is an image in which Beatrice is reading a song, accompanied by a guitar, amidst a field near Leonato’s house (where the action is to take place), while sitting in a tree eating grapes. The director uses an establishing shot, which introduces the scene’s setting and its participants[16]. A messenger announces the approach of Don Pedro of Aragon, which creates an excitement amongst the people in the villa who rush up to bathe and dress themselves up for the occasion. The arrival of Don Pedro and his men is performed with glorious music and a powerful imagery which sets the mood of victory and power; whilst in the text his arrival is merely announced and this bucolic scene is absent.

These engaging images are possible considering the new techniques which give cinema new possibilities when compared to theatre. The camera helps the audience to approach the subtle differences. The camera allows the director to show the audience his understanding of events, especially when it comes to a character’s reaction to a given characters and know them deeply, and, as Shakespeare is a playwright who does not specify concrete stage directions, Branagh has a complete freedom to perform and interpret the play. The camera allows Branagh to show the audience his understanding of the events, especially when it comes to a character’s reaction to a given comment, and feeling free to communicate a message not given within Shakespeare’s lines through actors’ gestures and movements. For example, the scene in which Beatrice listens that Benedick loves her may be ambiguous in the initial text, but through focusing on facial expressions and the tone of her speech, Branagh’s version implies that she is delighted with the idea.

Branagh’s Messina is different from the play’s text, yet the general message of the play remains unchanged as Shakespeare had the quality of being everlasting and contemporary for our time. His adaptation to cinema has had the need of making the film more versatile and more entertaining for general public, as well as more dynamic and profitable. In order to do so, Kenneth Branagh made use of technologies and conventions which theatre lacked, making a product which is completely open to all public. This film gives an ordinary person the chance to get some insight into Shakespeare’s text, yet we must keep in mind that certain subtleties were incorporated and many omitted and therefore, we must be aware that our sensory system can be conditioned by a more “image based world” rather than that Shakespeare truly cared of: a world based on words to create images.

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1999)

Plot

and structure

We are going to deal with A Midsummer Night’s Dream written by William Shakespeare around 1590, and according to Antonio Ballesteros who made the prologue for El Sueño de una Noche de Verano from Biblioteca Edaf, 9th edition September 2004, it is included in the author’s first creative stage for entertaining in a wedding’s frame of nobility people at the time of the Queen Elizabeth I. The main topic of the play is the love that ends in marriage.

In the play there are three connected stories that happen in Athens. The first one tells us how Hermia, Egeus’ daughter, is in love with Lysander and he corresponds her too, but their relationship is not possible due to Demetrius also loves her and he has Egeus’ approval. At the same time, Helena, Hermia’s friend, is in love with Demetrius.

Egeus decides to visit Theseus, who is going to marry Hyppolita, asking for help because he is convinced that his daughter has to obey him and she has to marry Demetrius. In a meeting at the palace, Theseus says Hermia that she has to find a solution to her problem or she will be killed according to the ancient law of Athens, as her father wants. It is when Hermia and Lysander decide to escape into the forest.

Somewhere else, a group of comedians prepare a performance for Theseus and Hyppolita’s wedding. Once all the characters are been handed out they go to rehearse into the forest.

And the third story happens into the Fairies’ world (in the forest too) where the King Oberon and the Queen Titania have got angry with each other due to Titania has a magic child that Oberon wishes to have.

At this moment, the three stories become one: Oberon orders Puck, his friend and servant, to look for Cupid’s Flower, which has the power to make a person falling in love with the first being he/ she sees. One victim is the same Titania, who falls in love with one of the comedians, Bottom. Oberon thinks when his wife realises she is in love with Bottom, she will give him the child. All this happens as he likes it. The conflict comes with the four loving youths of the beginning, as what Oberon wanted is that Demetrius loves Helena and Hermia and Lysander gets a free way, but Puck confuses the two boys and they both become in love with Helena.

At the end, Oberon and Puck find the solution and Hermia and Lysander keep with their relationship while Demetrius corresponds to Helena’s love. Titania returns with her husband just after he has got what he wanted and Bottom thinks that everything has been a dream.

In the morning, the four loving youths are invited by Theseus and Hyppolita to get married with them together (each one with his/ her partner) and Bottom with the rest of the comedians perform a play in the multiple wedding, getting a great final success.

The film follows closely the structure of the original Shakespearean text, this is why it is not difficult to us to follow the movie, as it reproduces act by act in the same order than in the play. In this case, the director has chosen a simple way of narration, since he has not used any cinematographic narrative technique to alter the linear development of the action such could be a flash-back. It is for this reason that we can divide our analysis about the film in the same acts that in the book.

First of all, what we did was to research differences and resemblances between the text and the film in order to demonstrate the film director’s fidelity to Shakespeare.

The first difference we found is that enough dialogue from the text is rejected and in its place a conversation between Hermia and Theseus appears where Hermia admits that she prefers to die instead living without Lysander.

The second important difference is the introduction of the character of Helena, it is very different from the play, because she appears with a bicycle in Theseus’ garden, instead the dialogue between her and Hermia that we see in the text.

Third, in the film the lovers kiss each other at every moment, but in the play Hermia seem to be too pure to kiss a man.

Very important is the fact that the comedians in the play seem to be poor people, you expect to see a person with casual clothes, but in the film you can see people with suits, ties and other formal items, as if they belong to a higher class.

Another important difference is that in the play Shakespeare says that the characters go on a pilgrimage (they are walking around the forest) but in the film the characters ride bicycles.

It is really funny when, in the film, Puck rides a tortoise and then he steals the bicycle from Lysander. In the text Puck says he is the fastest in the world, it seems to be a satire in the film because a tortoise is the lowest animal. Stealing the bicycle he demonstrates that it does not matter how he moves, he can use a turtle or a bicycle or just his feet because he will always be the fastest creature in this imaginary world.

We cannot forget that in the text Bottom treats the five Fairies as men, but in the film these Fairies are women. In the play we do not know about the genre of the Fairies.

On the other hand, in the film Hermia fights against Helena while in the text they only have words.

Furthermore, in Shakespeare's text Hermia, Lysander, Demetrius and Helena fall asleep due to their tiredness when Puck makes them follow him running, but in the film it seems that the magical atmosphere makes the characters feel tired until they fall asleep.

Besides, after supposing in the play that Bottom and Titania have had sexual contact, he starts to ask the Fairies for food, he tries to order them as if he were their King, however in the film the sex is explicit and he does not try to be the leader, there is an omission of the original text.

Then, when Theseus and Hippolyta arrive in the forest they find Helena, Hermia, Demetrius and Lysander lying together, but in the film they are naked, something that Shakespeare never says, and never could say, but meant. At the same time, when Bottom falls from the bed in the film he finds Titania's ring and this makes him doubt about if he has had a dream or if it was reality. In the play when he weaks up he leaves the forest without finding a ring.

On the other side, there is a very important similarity between the play and the film, it is the pun: "Bottom's dream because it hath no bottom". It appears in both cases. This time the director is actually very faithful to the text and the spirit of the play. Life is but a dream. Another similitude between the play and the film is the way it ends with the conclusion made by Puck (a monologue).

Coming back to the differences, we must say that in the text there is a prologue to the interlude (Pyramus and Thysbi's comedy), but in the film this prologue is a little introduction made by the Wall.

Secondly, in the play while the actors are performing the interlude, the audience is gossiping about the way they are carrying out the play. In the film the audience is impressed and they say nothing and the performance is not interrupted.

Finally, in spite of the last words we hear in the film are the same we read in the text, the last image we watch in the film is the comedians being drunk and celebrating they have performed a truly notable performance.

Characters

When a book is adapted to the cinema, the election the director makes about the casting is very important. It is easier to attract spectators’ attention with famous actors and actresses at the top of the cast, because when people go to cinema prefer to watch a movie with a known person as the main-character. This makes that a casting could change depending on the year it is adapted, for example in 1995 Julia Roberts was the actress of the moment and last year Sarah Jessica Parker made a lot of films getting the role of women of the year.[17]

In

this adaptation of Michael Hoffman, some examples are Oberon and Titania, who

are very important in the book, as the great majority of the plot goes around

them and the director chose Rupert Everett as the King of the Fairies and

Michelle Pfeifer as the Queen of the Fairies. He was so known thanks to his

role as the gay friend in the film My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997) whereas she was so famous because her

main-character in Dangerous Minds (1995). [18]

Two famous actors to play two important

characters. But it is more curious when a famous actor/actress embodies a

secondary character because it becomes more eye-catching and it has as much

importance as the main roles. It is the example of Helena, who in the play is

in the same plane as Hermia, Lysander or Demetrius, but in the film she becomes

a higher shot. She is Calista Flockhart, very famous in 1999 thanks to her role

in the serial Ally McBeal, which

was broadcasted from 1997 to 2000.[19]

Another character with the same case is Bottom. In the play, he is like a puppet that is handled by Titania, Puck and Oberon. We can see him as a secondary actor at the mercy of the main-characters. But in the film he is Kevin Klein: A Fish Called Wanda (1988), French Kiss (1995) or In & Out (1997), and this gives a lot of importance to him, we recognize Kevin Kline and obviously we recognize Bottom.[20]

On the other hand we have characters that in the play are principals, but in the film they are people we cannot recognise as famous, and directly, we forget them and we pay more attention to these characters performed by actors and actresses we know.

It is here that we must talk about characters like Hyppolita, who in the play is the Queen of the Amazons and has an important rule, in the play becomes a lower level and we can only see her two times, at the very beginning and at the end when she marries Theseus. She is Sophie Marceau, a French actress.[21]

Egeus is an important character too, but in the film we can only see him when all the characters are at Theseus’. But at the end, we do not remember him and when he leaves the table at his daughter’s wedding, we must watch the scene twice to realise who is him. The actor who roles Egeus is Bernard Hill, Captain Smith in Titanic (1997)[22].

Having seen who is who in the film, we can talk about some aspects that differ between the play and its adaptation. Firstly, all the characters in the play appear in the film. The director has been very close to the real text, obeying the importance of the main-characters. He has only changed some minor things to get the spectators’ attention; this is to play prominence of some characters down, like Hyppolita and Egeus. However he has not changed the plot, instead of that, he has only managed the information to be closer to the audience.

Secondly, the fact of known actors/ actresses performing the main-characters, benefits the development of the plot around these characters. In this play this fact is important because the director is making easier to understand the plot, which is very complex in the real text, but as the audience knows the actors and actresses, they follow easily the plot, it is a technique to make the play enjoyable.

Finally, we want to emphasise that the election of the cast depends on the moment the adaptation is made, probably taking into account who are the most famous actors and actresses that year.

Cinematographic

techniques

As cinematographic techniques we must underline that the director not only has largely taken benefit through the use of special effects, but also through the movements of the camera that he makes, without which he would not have been able to show some features of the characters as he does. Such as when the Fairies transform into fireflies and disappear flying.

Especially in this film, cinematographic techniques are almost indispensable. Thanks to them, the director makes the magical world closer to us, as Shakespeare tried to represent.

Michael Hoffman takes advantage of the budget with which he counts on shooting the film ($1.000.000) and he specially focus on capturing the audience’s attention through everything which is connected with senses.

On the one hand, he is able to surround you in a fantastic world from a particular and well-made wardrobe. The scene when Titania orders to the Fairies (Cobweb, Moth, Mustardseede and Peaseblossom) to take care of Bottom would be a good example of this. Then, apart from the characters’ make-up, colourful and trimmed costumes with any kind of bright element that wear the creatures of the forest keeps our eyes in this ideal environment. Also our vision is attached by the play on lights that the directors makes when the Fairies have become in fireflies.

On the other hand, everything that is connected with the resonant part would be divided into the sound track and music with which the director accompanies some scenes. We can distinguish a series of sounds and onomatopoeias in many scenes of the film that take place in the forest. All of these sounds are supposed to be from the animals of the wood, such as crickets, birds and owls.

As regards some songs that we find in this adaptation, we could say that there is a great number of melodies where we can hear typical instruments from the mythological beings like flutes and harps. But this only happens when the Fairies are on scene.

However, in the rest of the movie, the director has preferred to relate the facts with some well-known operas that can express the essence of the scene. The most famous opera that we are able to recognize is one from “La Traviata” ,the Choir Brindiamo to be more specific. It is used by the director in order to introduces us into the Athenian customs, as he can show us some streets full of people talking and going shopping in a market. This would be the scene where Bottom and the other comedians appear for the first time.

As for the special effects, we must enlight a particular scene where a trunk becomes a mirrow. It happens in the moment where Bottom is going to become into a donkey as Puck has bewitched a cane and a hat that Bottom puts on.

But the point at which the contribution of the special effects achieves its great splendor would be at the beginning of the movie when Titania and Oberon argue about the child. In this part, visual and resonant both aspects are linked to represent a heavy storm that the king and the queen have produced with their argument (the movement of the stones due to an earthquake, thunders, flashes and the wind).

Finally, regarding the movements of the camera, we have to stress that the majority of the scenes have been filmed using general shots which allow the audience to see the whole landscape of the forest. The most curious movement about we could talk, would be one where Oberon, in a monologue, is being shooting while he is lying on the floor and in a short time the camera begins to displace towards the left and another image appears while Oberon is talking, but then he is surprisingly in another place. You are not able to distinguish the displacement of Oberon because you are concentrating on the character’s speech.

10 Things I Hate About You (1999)

Plot

and structure

Plot

and structure

10 Things I hate about you is a typical American romantic comedy about teenagers in a High School with its even more typical happy ending. In this film we can distinguish the well-known characters usually present in this type of comedies such as the good-looking bad boy who ends being a good one, the friendly handsome boy who is the person chosen to organize and develop all the plot, the best friend who helps to get an aim (the desired Bianca), the pretty girl all the boys love and the bad one who nobody wants, etc. Moreover, the typical elements in American films are portrayed: the graduation ball, the big party in somebody’s house, alcohol, the High School and its football team (here with the peculiarity that it is a female team)… All these elements combine in a plot loosely based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.

The story starts when Cameron, a boy who has just arrived to a new school, falls in love with Bianca Stratford, a beautiful and popular girl. Michael Eckman, the newfound best friend of Cameron explains him that she is a forbidden girl because her father doesn’t allow Bianca to date before her sister Katarina does. Katarina is a rebel girl who doesn’t think in boys at all because she suffered some bad experiences in the past. Cameron and Michael decide to find somebody willing to date Kat, so that Cameron is able to date Bianca. They discover Patrick Verona, a tough guy with a bad reputation who could be the perfect date for Kat. Joey Donner, a self-centred rich model who is also interested in Bianca, helps them without knowing the real intentions and pays Patrick some money.

During the strange relationship and courtship between Patrick and Kat they fall in love with each other. Meanwhile Bianca falls in love with Cameron, who, just as in the original text, had become her teacher. At the end of the film Joey tells Kat that Patrick was dating her with her only because of money, and Kat, angry and sad, writes a poem the next day for her literature class listing the “ten things” she hates about Patrick; finally admitting that she can’t forget him. Patrick tries to apologize and with the money Joey paid him he buys Kat a guitar. This makes her love stronger and the film ends with three new formed lovely pairs: Patrick and Kat, Michael and Bianca and Joey and Kat’s best friend, Mandella (after the two discover a mutual love for Shakespeare).

Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew is divided in two different scenes that compound the prologue (the induction scene) and five more acts. Shakespeare does not offer precise time references, but the story is probably developed in one month. In Gil Junger’s[23] 10 Things I Hate about You, the story develops in one academic year approximately, since the main characters, Katharine and Bianca, start and finish the year in the high school. The film is set in the 21st century, in Padua High School, Tacoma (USA), while the play it is set in the 16th‘s century Padua (Italy). We can find many similarities in both the play and the film, like the names of the main characters. Apart from this, there are also many other references to Shakespeare’s plays or life in the film (the surname of the main characters in the film is Stratford, a reference to Shakespeare’s birthplace, for example). Each story is carried out in a different place but both have the same aim, that is, the father of Bianca and Katarina or Katharine desires the best for his daughters, and in the play he will not allow that her younger daughter, Bianca, marries until a husband is found for his older daughter, Katharine. In the film he will not allow his daughters to go out at night with boys because they are adolescents, and he maintains the idea: the younger daughter will not go out at night until the older daughter does. He is a gynaecologist and he is afraid her daughters get pregnant.

Characters

Regarding the characters and casting, the major characters are present in both works, and only the servants and those characters that just appear in the prologue disappear in the film. A middle-class American family would not have servants nowadays. However, the paternal figure of Baptista is maintained in the new version, but with a background that makes it easier for the audience to understand why does he adopt a conservative personality and why he is a male chauvinist regarding Kate and Bianca’s education. He is the unique character in both works that maintains a traditional personality and enables both stories not only to have a male chauvinist sense but also to have an exciting plot where a lot of suitors will fight to get the sweetie Bianca, and in fact, all of them must deal with Kate, who has an aggressive character in opposition to her sister. At the end of both works, Kate “The Shrew” is somehow transformed into a loyal, submissive girl.

Cinematographic Techniques

The first impression we get from a film is usually the most important to decide whether it is worthy or not. In this case, the opening sequence is filmed to catch our attention and in some way explains and anticipates the plot, and what will happen in the rest of the film[24]. In this film the opening sequence give us clues about the setting and the major characters involved in the plot (Cameron’s new friend, Michael, introduces all of them at the very beginning).

The story starts “in media res”, in the middle of the action, and the characters themselves explain the situation to the audience. After this scene, the director uses a long shot to show us the grounds of the high school and then, using a medium shot, the camera focuses on the main characters meanwhile he describes them. Despite of these shots the most important aspect in this film are the close-up shots because there are a lot of important romantic dialogues and with this type of angle we can distinguish better the reactions of the characters.

The locations and exterior shots are filmed in Tacoma and Seattle, Washington. The high school’s exterior was shot at Tacoma’s Stadium High School. A brief scene takes place at the Fremont Troll in Seattle and another one of Kat and Patrick’s date takes place at Gasworks Park.

One of the most important visual resources the director uses to show us how a character will be are their costumes, the clothes they use. In this 20th – 21st century film we can suspect or imagine how the characters are watching their modern clothes. There are different models: Patrick and Kat wear dark clothes at the beginning when they are supposed to be unsociable and while their personality develops their clothing changes too into colourful ones. We can also see that Bianca and her posh friends are all very well-dressed and they use make up, and all the boys of their same group are also very well dressed (the most noticeable is Joey). A third group may be the different “social” classes Cameron sees at the beginning of the film when Michael is introducing them. We watch the chess-team dressed with suits, well-combed… the hippies with big clothes and dreadlocks in their hairs while they smoke marihuana and so on.

In the soundtrack of the adaptation, that contains 14 different songs, the original song scripted for Patrick to sing to Kat to gain her forgiveness (I Think I Love You by the Partridge Family[25]) clearly stands out over the rest. The director gives great importance to music and he manages to maintain Shakespeare’s essence through modern music. It is especially important in the relationship of Kat and Patrick. For example, there is a poster on the wall of Kat’s room advertising the band called TheGits, whose lead singer Mia Zapata was killed in 1993. This goes along with Kat’s taste for bands like Bikini Kill and The Raincoats that Patrick uses to gain her confidence and friendship. They also go to a live concert of some of these groups.

Finally, we must say that the sound effects used in this film are diegetic sound, where the sound is seen in the moment it takes place but we can distinguish also some non-diegetic sound when commentaries are made and when they aren’t seen explicitly in the scene.

All of these technical elements are developed together so that the Shakespearean message gets to the audience.

Love's Labour's Lost (2000)

Plot and Structure

The original play was written by William Shakespeare between 1588 and 1597, probably in the early 1590s, and published in a quarto edition in 1598[26]. Historical and temporal context in Shakespeare’s play is not really clear. The historical data offered by the author does not correspond to reality so it is of little (if any) help. In fact, the only king of Navarre under the name of Ferdinand was Ferdinand the Catholic (1511). We can probably assume that the story was settled during Shakespeare’s time. The adaptation takes the action to September 1939, just before the war. It sure is a long leap but it is fully justified by the intention of making a musical comedy whose best examples were made around the 40s and 50s.

The main plot is the same both in the play and in the film: Ferdinand, King of Navarre and three friends decide to give up women and other carnal pleasures to dedicate themselves to academic studies during three years. The problem is that the Princess of France and three of her ladies have an appointment with the King and, inevitably, each one of the lords falls in love with one of the ladies. They try to hide it from their friends but everything is finally revealed. Unfortunately, the death of the King of France prevents the original play from getting a happy ending, although it is different in the film. There are records of a sequel titled Love’s Labour’s Won[27] in which probably everything ended as it is supposed to end in a comedy, but it has been lost. We do not know if this is the reason for the ending of Branagh's adaptation which we are going to deal with later.

The most remarkable feature of this adaptation is that it is a musical that follows the style of those of the 40s and 50s. This implies several adjustments in the structure, the plot, and the staging that make it differ from the original play.

Part of the original text is omitted in the adaptation and substituted by musical numbers, but the most important fragments are maintained. There are also several changes in the order of the events, which alter the original disposition of Shakespeare's work, especially at the beginning of the adaptation, when the characters are introduced. In the film there is a cut at the end of Act I, Scene I[28], and then begins the only scene of Act II. After that, the film goes back to show us the rest of Act I and goes directly to Act III, where there is a significant amount of lines missing[29]. The first scene of Act IV is completely omitted and substituted by a sensual mask dance.

In the film Branagh uses black and white informative bulletins, typical of the first years of the television, to summarize some of the events of the plot.

As an example of fidelity to the original play, we can mention the funny scene between D. Adriano de Armado and Moth[30], followed by the song "I get a kick out of you". On the one hand, the actor chosen to incarnate the character of D. Armado, that is to say, Timothy Spall (unforgettable his participation in "Secrets and Lies"), plays his role reflecting wonderfully the definition which, referring to him, is made in the original work by Holofernes[31]. On the other hand, it has for us the added interest of being a Spanish character; it is really interesting to verify the archetypical image of Spaniards which they had in Shakespeare's time and still have nowadays.

Characters

The film we have analysed, by the Shakespeare Film Company, was adapted for the screen, produced, and directed by Kenneth Branagh in 2000 and, apart from himself (as Berowne), the cast includes Natasha McElhone (Rosaline), Alicia Silverstone (Princess), Alessandro Nivola (King), Adrian Lester (Dumaine), Matthew Lillard (Longaville), Carmen Ejogo (Maria), Emily Mortimer (Katherine), Timothy Spall (Don Armado), Stefania Rocca (Jaquenetta), Richard Clifford (Boyet), Anthony O'Donnell (Moth), Nathan Lane (Costard), Jimmy Yuill (Dull), Richard Briers (Nathaniel), Geraldine McEwan (Holofernia) and Daniel Hill (Mercade)[32].

Regarding characters, the most surprising fact is that Kenneth Branagh, who was almost 40 when the adaptation was filmed, represents the role of Berowne, a young student around 20 years old. But, apart from that little detail, we have to confess that his performance is spotless.

Another peculiarity we have observed is that in the original play Rosaline is black[33] and Maria is white, while in the film it is just the opposite. Maybe Branagh wanted to enjoy the presence of Natasha McElhone as his partner (one of the privileges you can have when you are the director of a film and are responsible for the casting).

Another remarkable variation is that of the character of Holofernes, that in the film becomes Holofernia, the only woman that is allowed to stay in the court of the King because she is his tutor. Her old age is not a threat to the vows of chastity of the King and his friends (though that does not prevent her from flirting with her erudite attendant Nathaniel, a parson).

Cinematographic techniques

Kenneth Branagh takes full advantage in his film of a great number of the cinematographic recourses at his disposal. He moves the camera, combines all types of shots (long, medium and close-ups) and he does not have any doubt in changing the angle of them every time he considers that the occasion requires it. Naturally, as we are dealing with a musical, music has a very important part to play. In this case, as well as the contribution from Patrick Doyle, the film brings to life songs of George and Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, Oscar Hammerstein II, Desmond Carter, Jimmy McHugh, Dorothy Field y Otto Harbach[34]. Concerning dance numbers, they remind us of Hermes Pan’s choreographies which were carried out by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers for the RKO, although there is a scene of a bathing in a swimming pool that is clearly inspired in Busby Berkeley[35].

There is a moment in the film which can be used as an example of all these characteristics we have been talking about. It is the part, about seven minutes long, with which Branagh puts an end to the film. The original play ends up with the separation of the protagonists because of the death of the King of France, and the promise that they will meet again, once the year of mourning has passed. In the film, however, Kenneth Branagh links the announcement of the king's death with the declaration of the war in Europe. He proposes an ending which, in our opinion, sums up magnificently what is meant by adapting a Shakespearean play, keeping loyal to its essence and making use of elements which can shock and scandalize the most puritan sectors. The four couples perform “They can't take that away from me" in what can be considered homage to the movie "Shall we Dance"[36]. Immediately afterwards, it is also paid tribute to the film "Casablanca". Next, we witness a succession of black and white images where real shots of World War II are mixed with others carried out by actors. Separation, destruction, pain, death, fall of France, resistance, the Allies' arrival and at last, the final victory and the reunion of the lovers in full colour. All together, it reaches its climax while we listen to those beautiful words of Berowne’s monologue: "And when Loue speakes, the voyce of all the Gods, make heauen drowsie with the harmonie... From womens eyes this doctrine I deriue. They sparcle still the right promethean fire, they are the Bookes, the Arts, the Achademes, that shew, containe, and nourish all the world."[37] Only just this moment is worth paying the ticket.

Just to finish, one last note. The members of the orchestra, in Act IV, wear wigs like Harpo Marx's. Another little homage in a film full of them.

We started this paper wondering about the way in which Shakespeare’s works have been adapted to cinema in the last century, from the Cinématograph to contemporary films, and also wondering about the success of those adaptations in their effort to transmit Shakespeare’s essence to today’s audiences. Through this paper we have collected evidence and opinions from scholars and experts trying to answer both questions.

The first one, the evolution of Shakespearean films, is answered in our analysis of history of films. We have witnessed that development from silent, black and white, one-scene adaptations like Le Duel d’Hamlet to 1996’s full colour, four-hour-long Hamlet, and also in the four different film adaptations that we have used as an example. Kenneth S. Rowell [38] summarizes in a simple way this effort of transferring Shakespeare to the cinema:

The history of Shakespeare in the movies has, after all, been the search for the best available means to replace the verbal with the visual imagination, an inevitable development deplored by some but interpreted by others as not so much a limitation on, as an extension of, Shakespeare’s genius into uncharted seas.

The second one can be easily inferred: if there are versions of Shakespearean plays through all of the history of cinema, it is because at least some of them were able to transmit the same ideas, themes and feelings of the original texts. Successful movies (both artistically and financially) like West Side Story or Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet are a consistent proof. In fact, many of these films are used by teachers around the world as substitutes to talk about Shakespeare’s plays (Michael LoMonico [39] tells us about this matter in detail) given the impossibility of assisting to theatrical performances of all the plays. So it really seems that these adaptations are worthy of being studied, therefore contradicting the vehement article by Charles Weinstein [40] we mentioned in the introduction, and not only that, many of these film versions are really enjoyable, even if they are not masterpieces. There is no doubt that some of these films manage to offer new and old audiences more than a glimpse of Shakespeare’s plots and characters.

Of course, as we have said through this paper, there are others who failed in this purpose, but the abstract and ethereal concept of “Shakespearean adaptation” is not to blame for those bad results. A Shakespearean plot (or just loosely inspired in one of the plays written by the Bard) is not a guarantee of a good film, that depends on the director and his idea about the film, on the actors and their performances, on the professionalism of the technicians… just as in a theatrical performance. Theatre and cinema are only two media (with many things in common) in which to perform a certain plot. Considering that one of them is superior to the other “per se” is only the result of an elitist view of culture.

For

the Introduction:

-Shaksper: The Global Electronic Shakespeare Conference. Hardy M. Cook. 16 December 2006 <http://www.shaksper.net/>

- Weinstein, Charles. “Towards a New Dunciad”. Shaksper: The Global Electronic Shakespeare Conference (28 March 2002) 16 December 2006 <http://www.shaksper.net/archives/2002/0831.html>

- Hearts, Andrew. “The Pound of flesh”. Panopticist (September 2001) 16 December 2006 <http://www.panopticist.com/articles/shakespeare.html>

For

the “Evolution of cinema and Shakespearean films”:

- EarlyCinema.com. 14 December 2006 <http://www.earlycinema.com/timeline/index.html>

-“Méliès, Georges,” Microsoft Encarta Online enciclopedia. 14 December 2006

<http://uk.encarta.msn.com>

- LoMonico, Michael. “Shakespeare on Films”. In Search of

Shakespeare

14 December 2006

<http://www.pbs.org/shakespeare/educators/film/indepth.html>

- Rothwell, Kenneth S. A History of Shakespeare on Screen: A Century of Film and Television. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004 (Second edition). - A preview of the book in pdf format can be found here: <http://assets.cambridge.org/052183/5372/excerpt/0521835372_excerpt.pdf>

-“Bernhardt, Sarah,” Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia – Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 15 December 2006

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Bernhardt>

-Jackson, Russell. The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000 - A preview of the book in pdf format can be found in the free service Google Books (<http://books.google.com>) searching for the Jackson, Russell.

-Hapgood, Robert. “Popularizing Shakespeare: The Artistry of Franco Zeffirelli” Shakespeare The Movie: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV, and Video. Ed. Lynda E. Boose and Richard Burt. London: Routledge, 1997. 80-94.

For

“Much Ado About Nothing”:

FIRST SOURCES:

-The Oxford Shakespeare. London: Oxford University Press, 1914.

-Branagh, Kenneth. Much Ado about Nothing. 1993.

-Establishing shot-Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. GNU Free Documentation License. Last modified 17 Nov.2006. 13 Dec.2006.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Establishing_shot>

- Cinematography-Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. GNU Free Documentation License. Last modified 17 Nov.2006. 13 Dec.2006.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinematography>

-Untitled Document. 13 Dec.2006.

<http://www.filmeducation.org/secondary/shakespeare/night2.html>

REFERENTIAL SOURCES:

-Internet

Shakespeare Editions. Best, Michael.

"Policy on Quality Content." Internet Shakespeare Editions,

University of Victoria, 2005. 14 Dec.2006.

<http://ise.uvic.ca/Foyer/quality.html>.

-Kenneth

Branagh’s 1993 Much Ado about Nothing.

Idylls Press, 1998-2005. 14

Dec.2006.<http://www.bardolatry.com/muchbran.htm>

-Comedy

in “Much Ado About Nothing”. A part of the

New York Times Company, 2006. 14 Dec.2006. <http://shakespeare.about.com/library/weekly/aa060100a.htm>

-Much

Ado About Nothing- Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. GNU Free Documentation License. Last

modified 16 Dec.2006. 16 Dec.2006.

<http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Much_Ado_About_Nothing>

For

“Midsummer Night’s Dream”:

-Rupert

Everett. Biografía, filmografía y fotos.-El Criticón. Aloha Criticón 2001-2006. 14 Dec.2006.

<http://www.alohacriticon.com/elcriticon/article1563.html>

-Michelle

Pfeiffer. Biografía, filmografía y fotos.-El Criticón. Aloha Criticón 2001-2006. 14 Dec.2006.

<http://www.alohacriticon.com/elcriticon/article1521.html>

-TodoCine:

Kevin Kline. 16 Dec.2006.

<http://www.todocine.com/bio/00131859.htm>

-Calista

Flockhart -Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre. Wikimedia

Foundation, Inc. Modificada el 11 Nov.2006. 18 Dec.2006.

<http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calista_Flockhart>

-The

Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Internet

Movie Database Inc. 1990-2006. 18 Dec.2006. <http://imdb.com/>

For

“Love’s Labour’s Lost”:

-Shakespeare,

William. Encyclopædia Britannica . 2006.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

16 Dec. 2006

<http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9109536>.

-Love's

Labour's Lost. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

16 Dec. 2006

<http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9000152>.

-Love's

Labour's Lost (Folio 1, 1623)

Internet Shakespeare Editions. 16 Dec. 2006

<http://ise.uvic.ca/Annex/Texts/LLL/F1/Scene>

-Love's

Labour's Lost The Internet Movie Database

Inc.1990-2006. 16 Dec. 2006 <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0182295/>

-Lawson, Mark: Here comes Shakespeare: The remix. Guardian Unlimited. Guardian News and Media Limited 2006.16 Dec 2006.

<http://www.guardian.co.uk/Columnists/Column/0,,238064,00.html>

-Trench, Philip: Love's Labour's Lost. Guardian Unlimited Film. The Observer. 16 Dec 2006. <http://film.guardian.co.uk/News_Story/Critic_Review/Observer_review/0,,155371,00.html>

For

“10 Things I Hate About You”:

-10 Things I Hate About You (1999). Internet Movie Database Inc.1990-2006. 16 Dec.2006. <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0147800>

-Untitled

Document. 15 Dec.2006.

<http://www.filmeducation.org/secondary/shakespeare/night2.html>

REFERENTIAL

SOURCES:

-10

Things I Hate about You. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. Last modified 14

Dec.2006. 16 Dec.2006. <http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/10_Things_

I_Hate_about_You>

-10

Things I Hate About You-Production Photos-Yahoo! Movies. Nell Minow. Yahoo! Inc.2006. 16 Dec.2006.

<http://www.movies.yahoo.com/movie/1800018548/photo/32810>

-Lenguaje del cine: tipos de plano. Enrique Martínez-Salanova Sánchez. 15 Dec.2006.

<http://www.uhu.es/cine.educacion/cineyeducacion/tipos%20de%20plano.htm>

Academic year 2006/2007

© a.r.e.a./Dr.Vicente Forés López

© Ana María Palacios Palacios

amapapa@alumni.uv.es

Universitat de València Press