On 13 August 1890, Charles L. Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) went to see a demonstration of Edison's new Phonograph. He noted in his diary: "It is a pity that we are not 50 years further on in the world's history, so as to get this wonderful invention in its perfect form. It is now in its infancy; the new wonder of the age, just as I remember Photography was about 1850." Dodgson had experienced the new wonder of photography at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, and then watched friends and relatives engage in this art form, and finally in 1856, he took up photography for himself. He was, indeed, a pioneer in this new wonder of the age.

Several books have been written on Dodgson's photography but few have given an accurate picture of his "one recreation." Until now, that is (says he immodestly). The new book, Lewis Carroll, Photographer, I hope, will become the standard reference for Dodgson's photography for many years to come. I worked on the book with Roger Taylor, a photographic historian, who includes an essay in the book that puts Dodgson's photography in its historical perspective and gives a detailed analysis of his photographic opus. My contribution was to identify and date some 400 images in albums and prints currently at Princeton University Library. I also wrote captions for all the photographs and included a listing of all known photographs taken by Dodgson, the first time this has ever been attempted. Today, I would like to show you some of those images, many not seen in public before until the book came out earlier this year. And I would like to tell you a little of my research in this area.

Photography was invented in the 1830s but was not generally available to the amateur photographer until the 1850s when the wet collodion process was invented. Dodgson took up photography as his hobby in 1856. By profession, as I have already mentioned, Dodgson was a mathematician, lecturing at Oxford University. His books for children were very much a sideline. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was written at the request of a real Alice, the daughter of Dodgson's college dean, Henry George Liddell. He took three of the dean's daughters, Alice, Lorina, and Edith, for an afternoon boat-trip on the river that runs through Oxford, and during this gentle excursion he began entertaining the children with a tale of Alice who follows a White Rabbit down a rabbit-hole into Wonderland. The story was written out in manuscript and later bound and given to Alice Liddell who had inspired the tale. It was then published in 1865, and has since never been out of print in the United Kingdom. But all this you already knew.

Long before this story was told, when the children were very young, Dodgson met them in the Deanery Garden and they became great friends. Later he took photographs of them. Here (on the left) is five-year old Alice Liddell taken by Dodgson in June 1857; the little girl who we hold responsible for probably the best known story ever written for children.

She was the second daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, born in 1852. As you can see, she is a natural photographic subject, patiently enjoying the process of having her photograph taken, sitting still for about 10 seconds or more, unlike today's quick snaps. In order to achieve good pictures the sitter and the photographer needed a bond between them, rapport, a sense of mutual co-operation, two people committed to the same purpose. It works if the sitter and photographer know each other; are friends with each other. Otherwise, photographs taken in this era came out stiff and stilted, formal and false. Alice reminisced that "when we were thoroughly happy and amused at his stories - he seemed to have an endless store of these fantastical tales - he used to pose us, and expose the plates before the right mood had passed. Being photographed was therefore a joy to us and not a penance as it is to most children."

And here (on the right) is Alice's big sister, Lorina Liddell, aged 8, taken in 1857 at the same time as the previous picture. You will remember that she appears as the Lory in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Alice "had a long argument with the Lory, who at last turned sulky, and would only say 'I am older than you, and must know better'; and this Alice would not allow without knowing how old it was, and, as the Lory positively refused to tell its age, there was no more to be said."

This is another photograph of Alice taken a year later in 1858. It is an unconventional picture for its day, a profile portrait, showing Alice with her modern-style haircut (short and dark unlike the fictional character that takes her name), head slightly bowed with hand clasping the back of the chair to prevent involuntary movement. The background is the sandstone wall in the Deanery Garden at Christ Church. It is a beautiful image. It reveals a photographer with a true sense of composition and style. Yet it was taken early in Dodgson's photographic career. He was, however, a man who appreciated beauty in art, a regular visitor to art galleries and exhibitions, a friend of famous artists of his day. To some extent, he saw photography as an alternative to painting and sketching. He was never satisfied with his own attempts to draw. Photography gave him an opportunity to use and develop his aesthetic and artistic abilities. Later, when he gave copies of his photographs to sitters and their families, he would inscribe the picture as "from the Artist" rather than "from the Photographer."

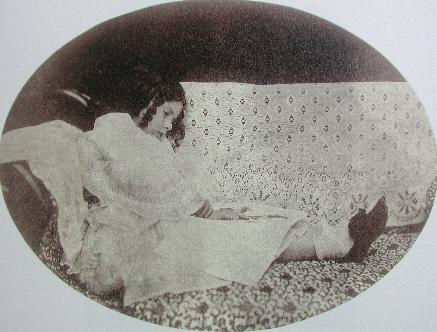

This photograph shows Alice's younger sister, Edith, aged 4, taken in 1858 on a sofa in what appears to be an interior setting. However, it was photographed in the Deanery Garden, Dodgson having erected a blanket wall behind the sofa placed on a carpet to give the illusion that the picture was taken indoors. A gauze screen above the sofa, not visible in the picture, gives diffused light, and since it was taken outdoors, the light is strong enough for a good exposure. Edith is nestled into a corner of the sofa. This makes her comfortable and less likely to move. Even slight movements spoilt the picture - the glass negative became blurred; and all the effort needed to prepare, expose, and develop the plate was in vain. Wet collodion glass-plate photography was fraught with such difficulties.

Dodgson parodied the complex process of photography in an early poem entitled "Hiawatha's Photographing" dating from 1857.

From his shoulder Hiawatha

Took the camera of rosewood -

Made of sliding, folding rosewood -

Neatly put it all together.

In its case it lay compactly,

Folded into nearly nothing;

But he opened out the hinges,

Pushed and pulled the joints and hinges,

Like a complicated figure

In the second book of Euclid.

This he perched upon a tripod,

And the family, in order,

Sat before him for their pictures -

Mystic, awful was the process.

Dodgson's own compact, folding camera was made by Thomas Ottewill and Company and bought directly from the makers in London for £15 (a considerable sum in that day). It was delivered to Christ Church on 1 May 1856.

"Hiawatha's Photographing" continues:

First, the governor - the father -

He suggested velvet curtains

Looped about a massy pillar.

And the corner of a table -

Of a rosewood dining-table.

He would hold a scroll of something -

Hold it firmly in his left hand;

He would keep his right-hand buried

(Like Napoleon) in his waistcoat;

He would gaze upon the distance -

(Like a poet seeing visions,

Like a man that plots a poem,

In a dressing-gown of damask.

Grand, heroic was the notion:

Yet the picture failed entirely,

Failed because he moved a little -

Moved because he couldn't help it.

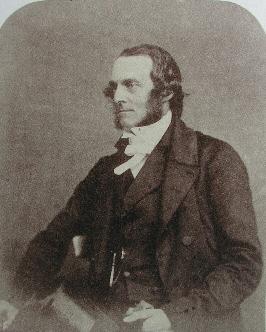

Here, the Rev. John William Smith, father of several children, is photographed by Dodgson, not with velvet curtains or massy pillars or protruding furniture, but with strength of character, holding his top-hat in his left hand, looking away from the camera (so that slight blinks of the eye did not spoil the picture), in a confident pose that reveals his station in life, Rector of Dinsdale, Yorkshire.

Next his better half took courage -

She would have her picture taken:

She came dressed beyond description,

Dressed in jewels and in satin,

Far too gorgeous for an empress.

Gracefully she sat down sideways,

With a simper scarcely human,

Holding in her hand a nosegay,

Rather larger than a cabbage.

All the while that she was taking,

Still the lady chattered, chattered,

Like a monkey in the forest.

"Am I sitting still?" she asked him:

"Is my face enough in profile?

Shall I hold the nosegay higher?

Will it come into the picture?"

And the picture failed completely.

This portrait shows Mrs. Mary Ellison, taken on 23 August 1862, wearing, probably by choice as was her prerogative, a gorgeous dress but lacking the nosegay and all the other attributes that would have doomed the photograph to failure. Dodgson photographed her husband and all of her children.

Here we see Constance and Mary Ellison, two of the children, in a very informal and relaxed pose, resting in the garden after a game of cricket. Dodgson entitled this picture "Tired of Play."

Dodgson is probably best known for his photographs of children. Very few amateur photographers at this time were attempting pictures of children because, in many cases, they were fidgety and impatient sitters. The vast majority of photographers at this time took landscapes - not much chance of sudden movements apart from wind and flowing water. Dodgson also took landscapes, but this forms only a small fraction of his photographic output - probably about 4% of all the photographs he took.

Let me show you a couple of his topographical pictures.

The first is Magdalen Tower, Oxford, seen from a distance with a family group posing beside a bridge. This was taken in the summer of 1861. He must have had the co-operation of the figures because they remain motionless as the picture is taken. Very recently, we have discovered who these figures are; they are the family of Professor Benjamin Brodie, who held the chair of chemistry at Oxford. They lived just to the right of the photograph. I am grateful to one of the assistant curators of the History of Science Museum at Oxford for this identification. The figures add interest to what would have been a very static image. Magdalen College with its grand tower is one of the magnificent colleges in Oxford. On the 1 May, each year, as the dawn rises, the choirboys of the college chapel take the winding steps up to the roof of this tower, and they sing to the dawn. Below, large groups of undergraduates and local people assemble to hear the choir sing. Traditionally, the students return to their respective colleges and partake in a champagne breakfast. Oxford has a number of fine customs such as this.

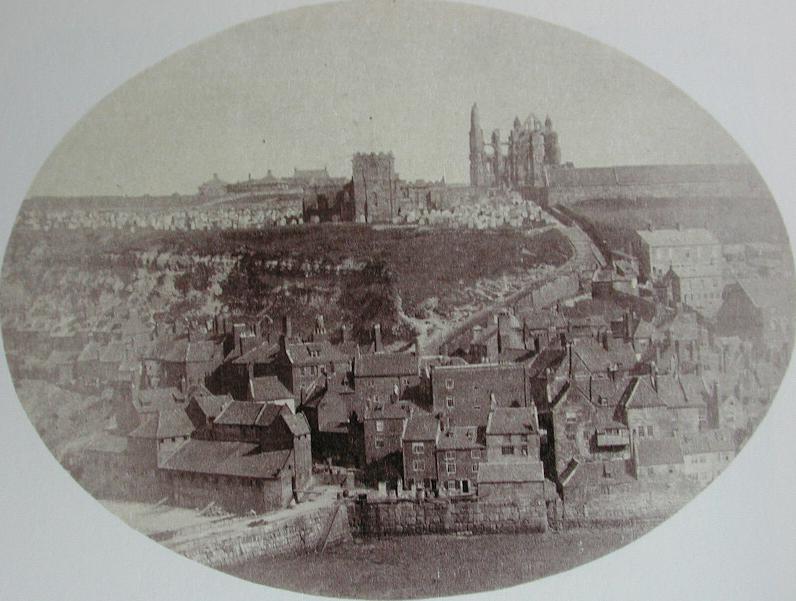

The second scene is Whitby, a seaside resort in Yorkshire, well known to Dodgson because he visited the town on several occasions. The ruined Abbey can be seen in the distance, to the right of St. Mary's Church. In the foreground is the fishing port. Much of the coastline visible on the left of the photograph has now eroded and fallen into the sea, including large sections of the churchyard. This was the haunt of Bram Stoker's Dracula; the author resided at Whitby. Dodgson, as a young man of 22, spent most of the summer here working with Professor Bartholomew Price and several other undergraduates preparing for the mathematical finals. He described an event that occurred in the meadow beside the ruined Abbey. The Oxford group organised a Sunday afternoon tea-party for the local children. A sudden downpour of rain left them all drenched, but one of the undergraduates decided to organise races to help get the children dry. And there were prizes of a half-penny. This event stuck in Dodgson's mind and he was to re-use the idea in Alice's Adventures eight years later in the Caucus Race in which the animals that had fallen into Alice's tears run races organised by the Dodo, and everyone had prizes.

In preparing the photography book, I did a count of the various types of photographs that Dodgson took. About six percent are of Dodgson's own family; his brothers and sisters, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Thirty percent are of adults or family groups. This includes a number of Victorian celebrities you may have heard of such as Alfred Tennyson, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Huxley, Samuel Wilberforce, Michael Faraday, George MacDonald, Ellen Terry, John Everett Millais, Lord Salisbury, and Queen Victoria's fourth son Prince Leopold, to name but ten.

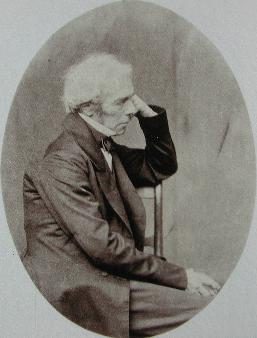

This is his portrait of Michael Faraday, scientist and professor of chemistry, discoverer of many of the properties of electricity and magnetism. It was taken on 30 June 1860 on the occasion of the meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at Oxford. At this same meeting, Huxley and Wilberforce debated the new theory for the origin of species proposed by Charles Darwin. Dodgson was at this important event, and invited many of the people attending to come to his studio set up in the Deanery Garden to have their portrait taken. Many came, and on this occasion Dodgson printed a list of the photographs he had taken, and even sold prints. Normally, he gave his prints as gifts to his sitters, but he was not against a little commerce to help pay for his expensive hobby.

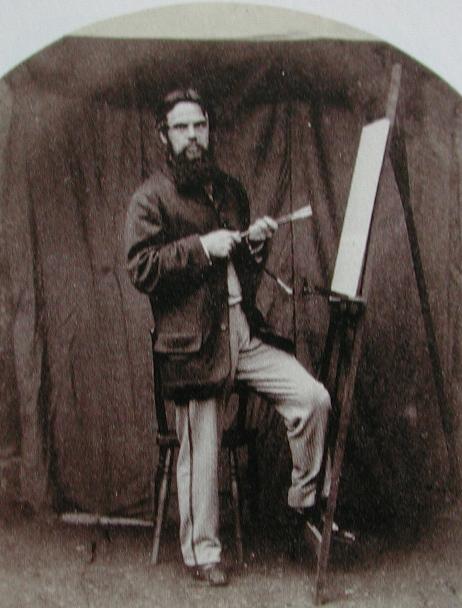

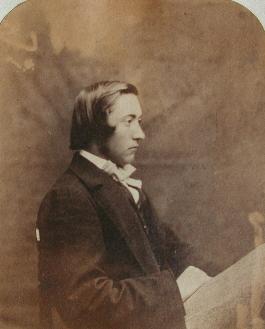

This is Dodgson's portrait of the Pre-Raphaelite artist, William Holman Hunt, also taken on 30 June 1860. Holman Hunt was the artist of "The Light of the World" - probably his most famous picture - and a founder member of the Pre-Raphaelite Movement with his two friends, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This picture was taken in the Deanery Garden, when the British Association was meeting at Oxford. Holman Hunt attended these debates.

Just over fifty percent of Dodgson's photographs are portraits of children. The remaining ten percent are best described as "miscellaneous" - pictures of artwork, still life and sculptures, live animals, assisted self-portraits, and skeletons.

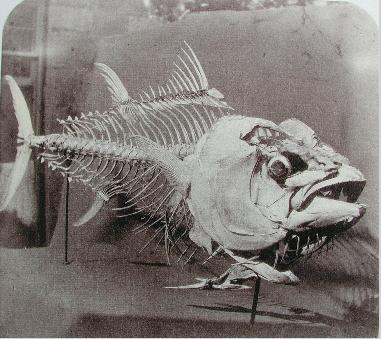

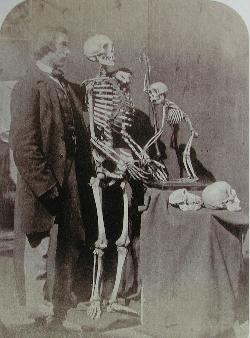

This blue-fin tunny-fish was caught off the Island of Madeira by fishermen, and acquired by Dr. Henry Acland who was attending to Henry Liddell, Dean of Christ Church, Alice's father. The Dean was spending the winter on this warm and dry island for the sake of his health. His friend, Acland, chose to go with him, to act as his personal doctor. Acland sent the tunny-fish back to Oxford where it was transformed into this skeleton for the Anatomy School at Christ Church. In 1857, Acland asked Dodgson and his friend Reginald Southey to photograph it, together with other skeletal specimens as a record of the contents of the Anatomy School. Later, these skeletons were transferred to the new Oxford University Natural History Museum, where you will find the tunny-fish to this day.

There is a myth that suggests Dodgson took only portraits of little girls. This is entirely untrue. Although girls form the majority of his pictures of children, there are many examples of boys photographed by Dodgson.

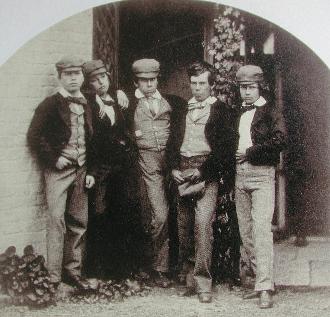

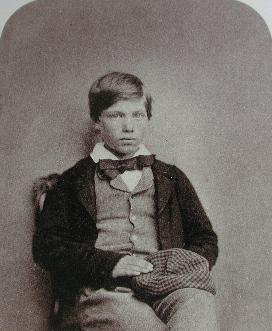

During the summer of 1859, Dodgson took his camera to a Boys' School at Twyford in Hampshire. He spent several days photographing the boys and the masters. This picture shows five boys with ages ranging from 14 to 16. Their pose is confident, even vane and precocious. Dodgson described the boy on the far left, Clement Malet, as "a remarkably nice-looking and gentlemanly boy." He took this single portrait of him.

Here he looks a little more vulnerable without his schoolmates around him. He went on to study at Pembroke College, Oxford, and was ordained deacon in 1872, and priest in 1873. Dodgson admired the physical beauty of both boys and girls, but he naturally preferred the company and conversation of girls.

Not many photographers would think of taking a picture of a girl up a tree looking through the branches. This very effective portrait is of Kathleen Tidy on the occasion of her seventh birthday. She was photographed somewhere in the Ripon area in 1858. Such photographs mark Dodgson out as an original and remarkable photographer who had an eye for unusual composition and a willingness to experiment with various unconventional ways of placing his sitters.

Look at the way he has grouped these four sisters. First, by bunching them together, he helps to reduce the chance of unexpected movement while the plate is exposed. These sisters, Lilian, Margaret, Ida, and Ethel, daughters of Professor Benjamin Brodie, Waynflete Professor of Chemistry at Oxford as I have already mentioned, form a natural arch, emphasised by the way the picture has been trimmed with a deep arched top. Margaret, second from left, has moved a little (no doubt because she couldn't help it) and her face is slightly blurred. However, the rest are motionless with the youngest, Ethel pretending to be asleep, her head resting on her sister's knee. But Ida, third from left is enjoying the whole process immensely, and is about to burst into laughter. Maybe she has seen the funny side of the story that Dodgson is telling them as the lens cap is removed. As a group, it shows a natural bond between four loving sisters. Dodgson rarely used external props to enhance the picture. The dark blanket backdrop and the girls' light coloured dresses focus the eye on the figures, and the different levels of their faces add interest to the picture. Overall, the result is a clever and effective composition.

In this picture, we see, again, two of the Brodies, Margaret and Lilian dressed in long flowing white material to mimic the features of a Greek statue. The dark blanket is seen draped against a brick wall, again bringing the figures into sharp focus and making them look sculptural. To emphasise his purpose, Dodgson added the children's names in Greek as a caption to the picture in his album.

When it came to larger groups, we see Dodgson's expertise in arranging the sitters. Hardly a face in this picture is on the same level as another. One boy is even perched up a ladder to stress this point. The matriarch sits just off-centre. She is Dodgson's Aunt Mary Wilcox; and around her are five sons, four daughters, a niece and a nephew. The brick wall forms an effective backdrop. There are no smiles. The idea of "say cheese" had yet to be adopted. Victorian people were not solemn as many of their photographs suggest. However, in order to take their pictures, an exposure time of about ten seconds was required, possibly longer depending on the amount of light and time of year, and holding a natural smile was difficult for most people, as it is today.

Some sitters did not find this a problem. This is Flora Rankin, a friend of George MacDonald's family, who came over for the day when Dodgson had his camera set up at the MacDonald home in Hampstead, London. Dodgson wrote in his diary: "Took a few more photographs. I have now done all the MacDonalds... and three children whom they brought in, Flora and Mary Rankin, and Margaret Campbell. Flora was the only one of the three particularly worth taking." And from this image, we can see the reason why. She loves having her photograph taken and is a natural sitter. Dodgson gave this photograph the title "No Lessons Today" summing up a child's feelings when school is out and it's a holiday. The photograph was taken in July 1863, but in 1872 Dodgson sent a copy to Charles Darwin who was writing a book with photographs entitled The Expression of Emotions. He thought Darwin might be able to use it to illustrate the emotion of joy, but sadly it wasn't used although Darwin wrote to thank Dodgson for sending it, and a copy of this photograph remains in the Darwin Archive at Cambridge.

Dodgson was very independent about his photography. He was not one to be influenced by other photographers. He established his own style. He knew other photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron, Oscar Rejlander, Lady Harwarden, and Henry Peach Robinson, and even acquired prints of their work, but he was resolute in following his own path. His Uncle Skeffington Lutwidge was an early photographer using the calotype method. Dodgson watched him taking photographs before deciding to take up the process for himself. He was taught the rudiments of the technical process by his friend and fellow member of Christ Church, Reginald Southey.

Southey was the nephew of the poet, Robert Southey, and he studied chemistry and anatomy at Oxford, later becoming a renowned surgeon at St. Bartholomew's Hospital, London. He took up photography a year or so before Dodgson, adopting the new wet collodion process. Dodgson watched him take photographs and they collaborated on a number of photographic sessions before Dodgson decided that he wanted to take it up for himself. Southey taught him how to prepare the glass plates, develop the negatives, and make the positive prints. He loaned his camera and chemicals for Dodgson to practise the art. He even went with Dodgson to London to help him chose a camera. Southey was very friendly with the Tennyson family, probably because of his family link with a previous Poet Laureate, and he visited the Tennysons on the Isle of Wight on several occasions. Julia Margaret Cameron lived close by, and it is very likely that Southey also taught her to take photographs.

I have already mentioned the skeleton photographs taken by Dodgson and Southey at the request of Dr. Acland. The two young photographers seemed to incorporate a sense of humour in their pictures of the skeletons, combining human skulls with cods' heads or apes, taking foreshortened views to distort the images so that a fish head was out of proportion with the rest of its body, and here, mixing the living with the dead. This picture of Southey and his "friends" was taken in June 1857 and may have been Dodgson's tribute to his colleague and photographic teacher who had just graduated at Oxford.

Many of Dodgson's early photographs were taken outdoors in the gardens of friends. He used the Deanery Garden at Christ Church for many portraits. He needed a room close by to prepare the glass plate in subdued light, and again to develop the image as soon as the plate had been exposed. The whole process followed in sequence without any loss of time. Once the plate was fixed, positive prints could be made as and when required. Early in his photographic career, Dodgson made these prints himself, but then he gave the task to professional photographers, supplying them with his glass plates. This saved him valuable time especially as he sometimes had a dozen or more prints made from his plates. During the latter part of his photographic opus, he returned to making his own prints.

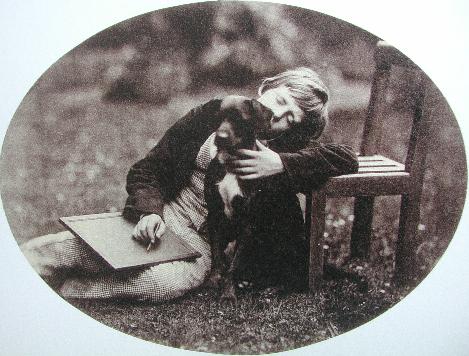

This is one of his outdoor pictures taken in the garden of his family home at Croft Rectory in Yorkshire. His camera and photographic equipment was often sent ahead by railway since it was too bulky for one person to carry easily, even though his camera could be dismantled and folded down to a manageable size. The glass plates and bottles of various chemicals were housed in a large strong wooden box made with iron brackets and reinforcements. Added to these were blankets and gauzes, tripod, equipment and utensils for developing the plates, and templates for trimming prints. He often took albums of his photographs with him to show potential sitters, thus demonstrating his skill in this new art form. The little chair you see in this picture showing his brother, Edwin, and the family dog Dido, is seen in other photographs, so he may have carried this around too. Although pretending to be asleep, Edwin holds Dido so that he doesn't move. The slate lies unused on his lap. The picture is entitled "The Young Mathematician." Edwin studied at Twyford School and after a short spell working for the Post Office, became a missionary in Zanzibar and on the Island of Tristan Da Cunha.

In 1863, Dodgson rented a studio for photography at Badcock's Yard in the same street as his Oxford College. For six guineas a year, he had access to a large room with plenty of windows for light, but shelter from outdoor weather. He was able to install some basic furniture, chairs for his sitters, and store his photographic equipment.

This photograph of Alice Emily Donkin and Alice Jane Donkin was taken in this studio on 14 May 1866. They were cousins. Dodgson entitled this picture "The Two Alices." Alice Jane on the right later married Dodgson's brother Wilfred in 1871 and therefore became Dodgson's sister-in-law. Alice Emily Donkin did not marry but became an accomplished artist. One of her pictures, based on a photograph taken by Dodgson, called "Waiting to Skate," hung in Dodgson's rooms at Christ Church.

In 1868, Dodgson moved to new rooms in Christ Church. This was a large suite on the second floor in the north-west corner of Tom Quad. Dodgson saw the potential for a photographic studio being built on the roof, and after gaining permission from the college authorities, the studio was constructed. His first photograph taken in this new studio is dated 17 March 1872. The studio was situated behind a large Tudor chimney stack with windows on one side, accessed by a staircase from his rooms, and with an additional dressing-room for his sitters. The studio was heated, so he could use it throughout the year. Normally, he only took photographs from late spring to early autumn when the light was strong enough.

This photograph of Beatrice and Ethel Hatch was taken in his Christ Church Studio on 24 March 1874. They were the daughters of Edwin and Bessie Hatch; he was Principal of St. Mary Hall, Oxford, and later Reader in Ecclesiastical History. The parents had no objection to Dodgson taking nude studies of their daughters, and Beatrice was happy to be photographed in this manner. Dodgson made a nude study of her in 1873 when she was aged seven.

Much has been said and written about Dodgson's photographs of very young children in nude studies over the last few years. Today, we quite naturally wonder about his motives. However, it must be said that in the context of Victorian society and values, such pictures were seen as aesthetically acceptable and to be admired as art. I have read suggestions that Dodgson took hundreds of nude photographs of children. I find this to be inaccurate. The truth is that eight families allowed him, and probably encouraged him, to take photographs of their children without clothes. The number of such photographs taken is small. He recorded the vast majority of the photographs he took in his private journals, and this revealed around thirty photographs of either nude or semi-nude children. This would represent around 1 percent of his photographic output. The topic seems to focus the minds of people today, yet it is a very small proportion of the 3000 or so photographs that he took over a period of 25 years. Six such photographs survive, none at Princeton, hence I have no images to show you, but they have been reproduced many times in modern biographies of Dodgson. Three show members of the Hatch family, one shows two sisters from the Henderson family, one is baby Bertram Rogers lying on a cushion, and the remaining picture, not yet published, is of baby Benjamin Brodie asleep on a couch.

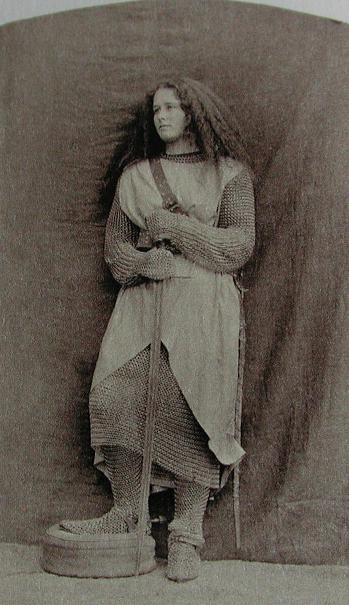

More profuse are his photographs of children dressing up rather than dressing down. Costume photographs were a particular feature and favourite of Dodgson's output. He acquired costumes, borrowed them from museums, and even had some made, for children to dress up in. In typical Victorian manner, he enjoyed the notion of a tableau, especially one with a literary association. This picture shows Rose Lawrie in chain-mail borrowed from the artist, Henry Holiday, in "Waiting for the Trumpet," a title taken from Tennyson's poem, "Sir Galahad"-"A maiden knight; to me is given/ Such bliss, I know not fear."

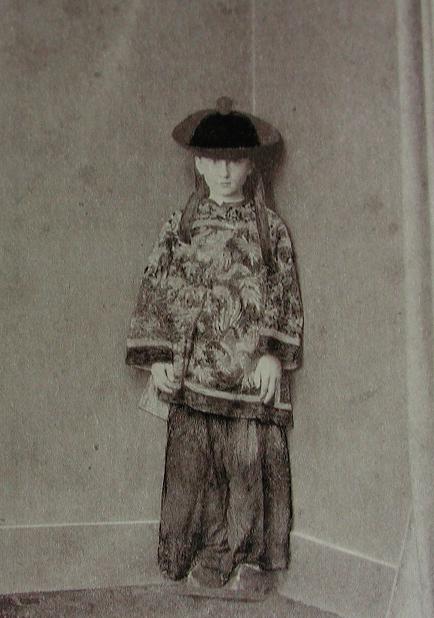

Next we see Helen Standen in Chinese costume, borrowed from Mrs. Foster who was once governess to the Liddell sisters. The Victorians had a great interest in all things oriental. Several other children wore this costume for Dodgson to photograph. We know that Dodgson also borrowed original costumes from the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford for his sitters to wear - South Sea Island and Japanese clothing and indigenous costumes of the first New Zealanders, normally on display in the Museum - something which would not be permitted today. His friend, the wife of Professor Bartholomew Price, made him a Greek dress for photography. He bought stage costumes from his friends in the acting profession for similar purposes.

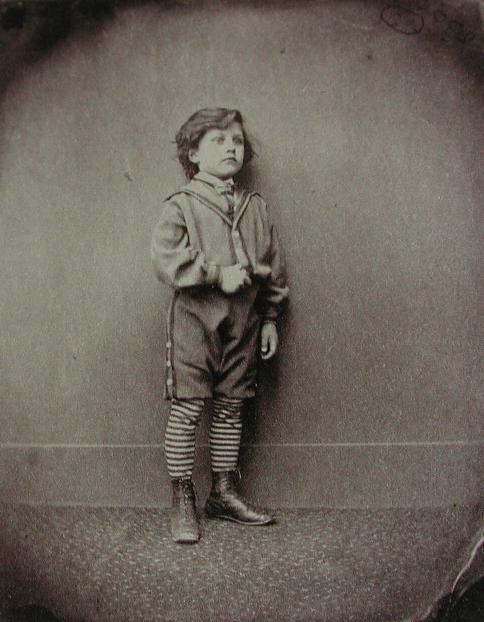

This picture shows Wilfred Hatch dressed in a sailor's costume, typical of Victorian boys of his age (he was seven at the time). He was photographed in April 1872 in the Christ Church Studio where many of these costume photographs were taken. Such photographs, as I have already mentioned, became a common feature in the last few years of Dodgson's photographic activity.

Here, the family of Kitchins, Xie, Herbert, Hugh, and Brook enact "St. George and the Dragon." Dodgson managed to get a large rocking-horse into his photographic studio, and the children have improvised costumes for the tableau, with a child draped in a leopard skin representing the dragon. Brook Kitchin sits astride the rocking-horse with wooden sword in hand, about to slay the dragon and rescue his sister, Xie, as the damsel in distress. Herbert, in cloak, lies on the floor having failed in his attempt to destroy the dragon. It is easy to imagine the fun the children had in playing out this game and then recording the activity in a photograph.

This is Brook Kitchin as "St. George" with a moustache painted on his lip and wearing his soldier's uniform. He is aged six in this picture. The date of the photograph is 26 June 1875, taken at the same time as the previous picture.

Xie Kitchin, the grown-up damsel we have just seen, was probably Dodgson's most photographed sitter. At least 50 photographs of her are known, from this picture of her taken in 1869 when she was just five years old until she was sixteen. She seemed to have a placid personality and enjoyed being photographed. She was patient, and, as this photograph reveals, she seemed natural and at ease in front of the camera. Dodgson once said that if you want to get excellence in photography, get Xie and put her in front of a lens - Xie-lens.

Here she is again, but eleven years later when she was a young lady and an accomplished violinist. This photograph was taken on 25 May 1880, just a few weeks before Dodgson put away his camera and took no more photographs. There has been much speculation about why he gave up photography. It appears to be a sudden decision. However, he usually packed away his camera in the summer before setting off for Eastbourne, the seaside resort where he spent his holidays. Sometimes he took a few photographs on his return in October, but in 1880, the camera remained packed away, and the studio unused. People have suggested that scandal about his nude photographs caused him to give up photography, but this is very unlikely. Such photographs, and we are not talking about very many, are spread throughout his photographic career, and he did not see these as cause for scandal, but perfectly respectable examples of his art as a photographer. The truth about his decision to give up taking photographs is revealed in a letter dated 8 December 1881 (MS. Jon Lindseth Collection) he wrote to Mrs. Hunt, now in the Jon Lindseth collection, in which he says:

The last photograph I took was in August 1880! Not one have I done this year: as there was no subject tempting enough to make me face the labour of getting the studio into working order again... It is a very tiring amusement, and anything which can be equally well, or better, done in a professional studio for a few shillings I would always rather have so done than go through the labour myself.

We know that from then onwards he used professional photographers, such as Kent's at Eastbourne and Debenham's at Shanklin, if he wanted a photograph of a child made for either the family or himself. Clearly, the process had become a drudge, and Dodgson was unwilling to spend the time and energy needed to keep his studio in working order, especially since it had become so easy to drop into a professional studio.

Finally, allow me to show you some of my favourite images from the four albums at Princeton University Library.

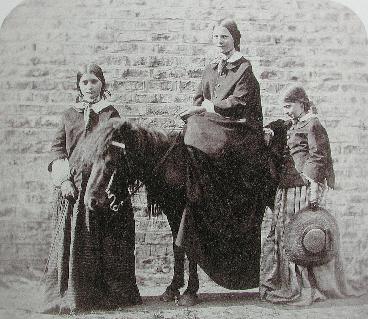

We have already seen the father of these children, Rev. John William Smith, Rector of Dinsdale. Here we see Fanny, Maria and Anne Smith with their pony, taken on 4 August 1857, one of Dodgson's early photographs. It emphasises Dodgson's priority in making the figures the centre of attention. The background is a plain wall, a common feature when the opportunity arose. On the previous day, Dodgson recorded his opinion of the Smith family in his diary. He wrote: "They are very pleasant and uniformly kind people; the children much what one might expect from their free country life, strong, active, handsome, and with a strong aversion to books."

The Twyford School Cricket Eleven pose for Dodgson's camera in a tent during the summer of 1859. The attitude of the boys is revealing. The chief batsman stands proudly in front of the wicket, leaning casually against his bat. Most wear their peaked caps, typical of schoolboys, giving them a sense of maturity and confidence. Face levels are very varied; three lie on the ground, but each takes a different pose, with arm resting on head or chin. Those on the first row sit on the bench in different attitudes, again confidently. Behind them, faces are placed just behind shoulders. The whole composition reveals a team of boys with a common purpose. The dark-haired boy on the back row on the right is Alice Liddells' brother, Harry. I recently met his great grand-daughter, who is also called Alice Liddell.

This photograph shows the Rev. Robert Salmon with the three-year-old Frances Bowlby sitting on his lap. As far as I can tell, there is no blood relationship between these two sitters. However, it is a gentle and appealling picture of a man giving comfort to a child. Perhaps she was shy about having her photograph taken alone, so he suggested that she sat on his lap and cuddled close. It says something about the innocence of the Victorian age; our overly suspicious minds, post Freud, about the relationships between adults and children and our concerns with the abuse of children in today's society would, sadly, question such a pose. In the same way that people criticise and raise alarms about Dodgson's nude studies, we fail to understand the Victorian way of life, their values and their sensibilities.

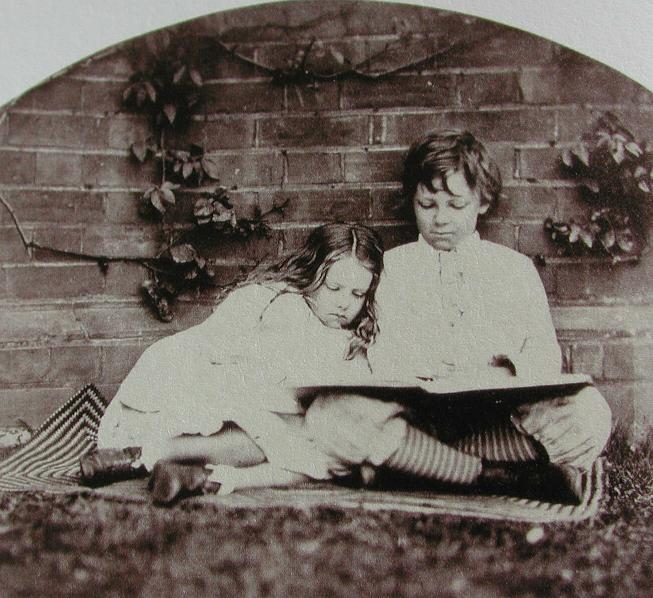

In this picture of Una and Harry Taylor, children of the novelist, Sir Henry Taylor, notice the angle of the camera; it is on the same level as the children's faces. This was another common ploy used by Dodgson. He rarely looked down on his sitters; he positioned the camera so that it looked up into their faces. He probably had to crouch low in order to set up this photographic image. The result is a charming picture of a brother and sister sharing a book.

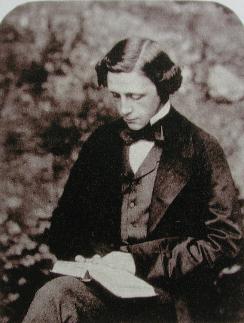

And finally, two portraits of the photographer himself; this is an assisted self-portrait taken in the Deanery Garden on 2 June 1857. Dodgson set up the camera and decided his pose and position, but he allowed Lorina Liddell to remove and replace the lens cap. He notes in his diary: "...and of course {she} considered it all her doing!" To summarise, Dodgson took photographs from 1856 to 1880, and during this time I estimate that around 3000 pictures were made. In 1875, he decided that he must catalogue his photographic opus and he spent about three weeks working on a register of his images. He chose to number each image, as far as possible in consecutive order. But he was attempting this task retrospectively, and hence he made mistakes. Sadly, the register he made is now missing but the numbers assigned to photographs remain against the indexes of his albums or on the back of loose pictures. I have spent many years collecting these image numbers and reconstructing the catalogue of his photographs. In the new book, I give a list of all the images and image numbers I have found so far. These numbers allow us to date his photographs with much more accuracy. From a number I can give the year in which it was taken without any doubt; I can often give the month in which it was taken, and on some occasions the actual day. Fortunately, Dodgson recorded his photographic activity in his diaries, and nine of thirteen volumes of his diary survive today.

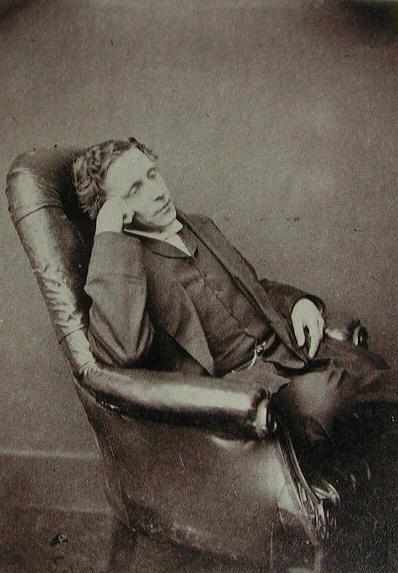

This self-portrait was taken when Dodgson was aged 43 years. It was one of the first pictures taken in 1875, and was probably a way to check that his camera and studio were in good working order before he began the task of taking other people's photographs.

I am going to leave the last word to my co-author, Roger Taylor, who wrote in our book the following statement: "What are we to make of the long span of Dodgson's photography now that it has more fully entered the public domain with this publication? Very few amateurs from Dodgson's period consistently photographed for so many years with little more reward than personal recognition as an artist and an extended series of friendships to sustain them... His concentration on portraiture ensured that he would never be short of material so long as he could get out and about and meet new and interesting families and their children. Concentrating largely, though not exclusively, on children as sitters enabled him to regenerate his enthusiasm with each new discovery... He was a polymath of remarkable talent whose legacy still enriches our lives through his literature and this extraordinary body of photographs."

*****

© Edward Wakeling 2003