J. M.

Barrie and

the Russian Dancers

Two years ago, in June

2005, I

published a book. My book. This event was the

culmination of eight months of research and writing: Research in an area

entirely new to me - that of the life and times of the Scottish author

and

playwright, J. M. Barrie (1860-1937) - and the writing of a book was a

new

experience, too, choosing to put myself in the shoes of my grandmother

and tell

her story as Barrie's housekeeper. But that's another story...

My point here is that the whole experience drew me into a new world:

the world

of J. M. Barrie and his devotees. The excitement of discovering 'new'

facts -

details never before mentioned in his biographies - still pervades and,

since

publishing my book, I have continued occasionally to dig and delve. New

findings, fresh thoughts and comments, are shared with

other 'Barriephiles'

through three dedicated websites (one British, one American,

one French),

and this is usually done by posting to their discussion forums.

Sometimes

documents are added to databases, etc, and, just occasionally, and with

a

little luck, a well-researched article may be accepted.

Fingers crossed!

J. M.

Barrie and

the Russian Dancers

I begin this piece with an acknowledgment for, if it had not been for a

simple,

innocent question - “Do you know something about 'The Truth about the

Russian

Dancers'?” - I might never have embarked on certain avenues of

research. I

happily admit that two weeks ago I knew nothing about the play by J. M.

Barrie,

but then I never could refuse an opportunity for a bit of sleuthing.

Céline-Albin Faivre, I am

grateful

to you for your question. I thank you for your invaluable help,

especially once

you received a copy of the 1962 publication of the play, and I admire

you for

your splendid, developing website devoted to Barrie -

www.sirjmbarrie.com - and

for all you are doing, through diligent research, writing and

translation, to

render J. M. Barrie and his works both accessible and appealing to

French-speaking people of the world.

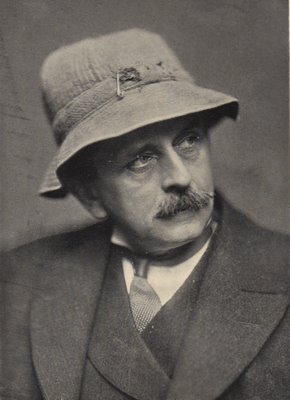

Sir J. M. Barrie

(1912)

Sir J. M. Barrie

(1912)

Most of Barrie's biographers seem to have been unimpressed with his

work 'The

Truth about the Russian Dancers'. Either that, or they simply chose to

ignore

it. In so doing they also omitted mention of the playwright's

associations with

two prima ballerinas: Tamara Karsavina and Lydia Lopokova. This article

is

therefore an attempt to collate such scraps of information as exist in

both

early recollections and more recent sources.

With respect to this topic the notable exceptions to the generality of

Barrie's

biographers are Cynthia Asquith, Janet Dunbar, who included some of

Karsavina's

recollections, and Denis Mackail, who described the play as “charming,

ridiculous, light, tender, and touching”, “an interpretation of the

world of

dancers as only one author could have seen it”, and “a very complete

entertainment ... in itself”. Yet Barrie's take was not only a satirical

comment on the ballet craze initiated by Sergei Diaghilev's ballet

seasons in

London around the time of the First World War. More significantly, it

was a

light-touch appraisal of the unique ability of Diaghilev's dancers to

give performances

which, despite the technical difficulties and peculiarities of dance,

seemed

natural and accessible.

The arrival of the Ballets Russes in London in the late spring of 1911,

led by

the dynamic Diaghilev, made a huge impact on an entire generation of

British

composers who were still in music school, or, as in Arnold Bax's case,

had not

been many years out. Somewhat surprisingly, perhaps, it seems also to

have made

an impact, some seven years later, on the "totally unmusical" Sir J.

M. Barrie. This lack of musical appreciation was observed by Peter

Davies who,

when aged seventeen, had taken his 'Uncle Jim' to the opera on two

successive

nights. A few days later, on 13th July, 1914, Barrie had written to

Peter's

brother George: “Both nights of Long Leave did he drag me to the

opera”. Years

later, when commenting on this, Peter wrote: “Being himself totally

unmusical,

[Barrie] not only did not encourage such leanings, but in one way and

another

could not help discouraging them . . . the fact is that music and

painting and

poetry . . . had a curiously small place in J. M. B.'s view of things.”

What,

then, happened to arouse Barrie's interest in ballet? Or, should the

question

rather be: how did Barrie become interested in two prima ballerinas of

Ballets

Russes?

Lydia Lopokova, only five feet tall and appearing a little dumpy when

compared

with the likes of Anna Pavlova, nevertheless had a captivating vitality

and

exuberance and, during 1918 and 1919, was celebrated for the roles

created for

her by the choreographer Léonide Massine in 'The Good-Humoured

Ladies', 'The

Fantastic Toyshop' and 'The Three-Cornered Hat'. Not only that, but the

ballerina, who in August 1918 had come to London via the United States,

where

she had married, had seen Maude Adams in 'Peter Pan' and had acquired an

admiration for Barrie and his books. And once she had achieved success

in

London she had written to Barrie and flatteringly asked him to write a

play for

her.

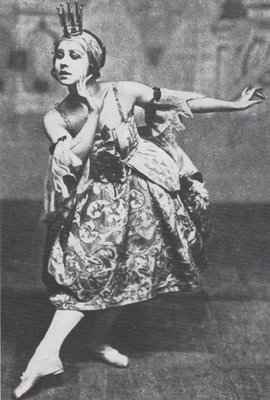

Lydia Lopokova

(1921)

Lydia Lopokova

(1921)

Thus it was that the playwright and the ballerina met, and a close

friendship

developed between the pair. She had an amusing, idiosyncratic way with

the

English language and, tellingly, an appealing childlike gaiety; on her

visits

to him 'Loppie' would sometimes sit on Barrie's knee. While the two were

matched also in height their ages were markedly different: Barrie was

then 58,

Lopokova was 26. In different circumstances, maybe, this age difference

might

not have posed a barrier to love but, by that time, the outgoing

ballerina had

also formed close friendships with various other eminent gentlemen, all

of them

at least 20 years younger than Barrie; these included Stravinsky,

Picasso, T.

S. Eliot and members of the Bloomsbury group, a tight-knit group of

English

intellectuals stemming from turn-of-the-century student friendship at

Cambridge, one of whose members was a six foot tall admirer with whom

she soon

started to exchange correspondence.

In the spring of 1919, in response to his new friend's request, Barrie

started

to write a three-act comedy about the imaginary and fantastic life of a

Russian

dancer, and he intended that Lopokova should star in it; she was to

have a

speaking part as Madamoiselle Uvula, and the play was to run at the

Haymarket

theatre. Whether the play would have been successful, and where the

relationship between Barrie and Lopokova may have led, we can only

speculate

because, on the 10th of July, when the play was about half written, the

famous

ballerina went missing. Her brief marriage to the ballet company's

business

manager, Randolfo Barrochi, an Italian whom she had married in America,

was known

to be breaking down, and immediately there sprang a rumour that she had

run off

with a Russian officer who she had met at a recent party at The Savoy

Hotel,

where she had been living.

Just two days later, however, she revealed to Diaghilev that she was

staying

with some Russian friends in St. John's Wood, not far from Barrie's

beloved

Lord's cricket ground and not a million miles from his home. To Barrie,

she

might just as well have been back in New York or St Petersburg, the

city of her

birth; his frequent attempts to communicate with his supposed friend by

telephone were to no avail even though she was aware of these. In a

letter to

Diaghilev, composed on the day of her disappearance, Lopokova wrote

that she

had had a serious nervous breakdown and, when pressed by a reporter for

The

Observer newspaper a few days later, Diaghilev explained that the

dancer was

ill. According to the Daily Sketch, however, Lopokova told them some

time later

that she stayed in her hotel for a few days and then went to France.

Whatever the truth about Lopokova's disappearance – and more recent

information

suggests that she remained in London, although the thoughts that she

had an

affair with a Russian officer seem not to have been dispelled - her

silence

towards Barrie must have seemed at least disrespectful and may have

hurt and

annoyed him. But, if it did, he kept this secret. And so there was

perhaps a

frustrated, if not emotional playwright, and a Russian dancer friend who

disappeared and said nothing to him. Little wonder then that Barrie's

work on

the full-length play ground to a halt.

Without much delay, however, for the late summer of 1919 would see the

playwright engrossed in 'Mary Rose', Barrie's imagination fired him to

start

modifying his idea into a play with a difference, a revealing and much

shorter

work. While the new play was not created specially for his absent

friend it is

tempting to wonder whether he might have thought it could entice

Lopokova to

return to him. As it was, Barrie had to contend with the unexpected

absence of

a leading dancer who spoke English with an acceptable accent. His

genius was to

become evident in his creation of a silent role. At the core of the

play's

plot, which was based on the courtship of Lydia Lopokova by a new man

in her life,

there was a female Russian dancer who said nothing and then was obliged

to

disappear (by dying). This clever reflection of recent events by Barrie

provided a pragmatic solution for him and for Diaghilev, although the

finished

play, if ever one of Barrie's plays could be considered finished, was

not ready

until the end of 1919.

'The Truth about the Russian Dancers' is a whimsical one-act play with

richly

romantic incidental ballet music commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev from

Arnold

Bax (who received a knighthood in 1937). It is set in "one of the

stately

homes of England, but it has gone a little queer owing to the presence

in the

house of a disturbing visitor". Subtitled “Showing how they love, how

they

marry, how they are made, with how they die and live happily ever

afterwards”,

the play features as its female lead a Russian ballerina named

Karissima who,

alone in the cast, dances instead of speaking; she dances rather than

simply

mimes all her part, including even the responses in her wedding

ceremony.

Although the overall tone of the work is lightly satirical, some of

Bax's score

has considerable emotional weight, especially the music concerning the

love of

the Ballerina for Lord Vere and her decision to bear him a child. This

costs

her her life since, when the new "Russian Dancer" is made living, one

must die to enable the greatness of Russian ballet to live on.

Being a dancer, though, the Ballerina gets to perform an encore after

her

death, and after the end of all dialogue. When it is time for her to

return to

her funeral bier, the ballet company's Maestro takes on the sacrifice

himself,

allowing her to live as a British aristocrat's wife and the mother of

the new

little Russian Dancer, already well-enough developed that she is chasing

butterflies in the garden while dancing on point.

But, with Lopokova now missing for five months, who should now play the

lead?

It so happened that Diaghilev's prima ballerina, Tamara Karsavina, who

was

dancing in London at the time, was connected by marriage to Kathleen

Scott (née

Edith Agnes Kathleen Bruce, afterwards Lady Scott, later still Lady

Kennet),

the widow of Robert Falcon Scott, naval Captain and famed explorer of

the

Antarctic, and mother of Barrie's Godson, Peter Markham Scott.

Karsavina had

married British diplomat Henry James ('Benji') Bruce in Russia in 1915,

and the

diplomat's father, Sir Hervey Juckes Lloyd Bruce, was a first cousin of

Kathleen.

Tamara Karsavina

(1921)

Tamara Karsavina

(1921)

It is not clear how the decision to offer the lead to Karsavina came

about,

although in retrospect it seems she was the obvious choice; she had

been a

Prima Ballerina for almost ten years. Understandably, Kathleen (Lady

Scott by

then), may have seen good reason to introduce Barrie to Karsavina soon

after

the ballerina's arrival in London in 1917 by taking him to see her

perform with

Ballets Russes. She knew that in June of that year Karsavina had made a

perilous flight from Russia with 'Benji' and her 17-month old baby,

Nikita.

This was just a few months before the Bolshevik Revolution, and they

had had to

escape without help from a distant cousin, Robert Bruce Lockhart, the

British

Consul-General in Moscow who, in different circumstances, would have

been able

to secure their safe passage. In any event, it is known that Lady Scott

took

Barrie on a special mission to visit Karsavina at the end of 1919. Here

is a

little of Karsavina's version of what happened:

“I have written a play for you,” he (Barrie) said in his peculiar

rasping

voice, and had a fit of coughing.

“I speak English with a Russian accent,” I replied.

“Oh, can you speak at all? I didn't know”

He then read the play. His strong Scotch accent, his cough, and to tell

the

truth, the play itself, rather overwhelmed me. I even thought at times

that he

was pulling my leg. After the reading he told me that he first intended

the

name Uvula for me, but it occurred to him that it might be taken as an

allusion

to the part of the palate so-called, and he changed it into Karissima,

which

should be spelt with a K so as to resemble my own name.

When she studied the script for herself, Karsavina understood the point

of

Barrie's remark, ”Can you speak at all?” She could not speak, according

to the

author, except with her toes. She found that the script had unspoken

lines for

her part, actually presented in the manner of stage directions, and it

was her

task was to translate those directions into movement – directions such

as:

'KARISSIMA is sad'; 'KARISSIMA makes movements which mean all this is

Greek to

her'; KARISSIMA is eager'.

The main theme of the piece is that the Russian dancers are not like

ordinary

humans. They are called into being by a master-spirit and can only

express

themselves through their own medium: “they find it so much jollier to

talk with

their toes.” I had before everything to establish beyond question with

my

public that Karissima's natural mode of progress was on her toes and her

utterance that of a being in possession of a language surpassing human

speech.

Questions to the playwright, seeking clarification on some points, were

sometimes met with unhelpful but not unfriendly answers:

“Don't ask me what I meant: I don't know myself,” he used to

say.

Karsavina realized that her aim should be to strike a delicate balance

between

the sheer extravagance of the play and the deeper feeling underlying

it. And to

do this she needed music which would have poetic quality as well as

rhythmical

value.

I was awed at the task of first choreographing my part within the

weird

frame of Barrie's play. Music, of the quality that Arnold Bax composed,

shaped

into form my first gropings. And ever since I knew that if I listened

to the

music, the shape and curve, the rounds and angles of the movement just

sprang,

as it were, from the sound.

During the rehearsals, Barrie often called out from the stalls to

delete or add

some lines:

Barrie, who attended rehearsals, altered, added, or changed the

script every

time, almost driving the actors crazy.

'The Truth about the Russian Dancers' first opened at the London

Coliseum on

15th March 1920, where it ran as part of a Variety bill for just a few

weeks.

The production was choreographed by Tamara Karsavina, and the sets and

costumes

were designed by British artist Paul Nash who, by that time, had made a

name

for himself in London's theatreland. The producer was the actor Gerald

du

Maurier, uncle of Barrie's 'lost boys' and father of Daphne, then aged

12. In

ballet and box-office terms its success was modest, however, owing, at

least in

part, to Bax's eccentric take on fractured dance rhythms; classically

trained

dancers couldn't dance to it. Nevertheless it was received warmly by

some drama

critics. A.B. Walkley of The Times was appreciative of Barrie's work

and the

infinite care with which the finished product had been polished; he

gave it

lengthy, enthusiastic reviews in two successive editions of the

newspaper. This

might not have surprised anyone, however, because Walkley was known to

be a

devoted follower of Barrie, engaging in dialogues with him. Only a few

months

earlier Barrie had reworked 'The Admirable Chrichton' in preparation

for its

revival and, in a reply to the critic, Barrie had written, “What does

touch me

a good deal is that you cared enough about Crichton to say

"hands-on". Your original writing about it gave me more pleasure than

I have got from anything else I can remember said about my plays.” Punch

magazine's reviewer, 'T', was generous with his praise of 'The Truth

about the

Russian Dancers': “But the triumph is the triumph of the whimsical

author. I

don't think he has ever done anything better; more ambitious things,

yes, but

nothing so free from flaw.” That the playwright had striven to hone his

play to

perfection became evident years later when Cynthia Asquith, his

secretary for

the last twenty years of his life, found ten different typescript

versions of

the play. And later still, Karsavina revealed her own script to be

version

number fourteen, although it is not known whether this related to the

1920

production or to the later one: the play was revived at the Savoy

Theatre in

1926, again with Karsavina playing the lead role, but it ran for just 37

performances, never to be seen again.

Barrie's friendship with Tamara Karsavina grew throughout the

preparation and

first production of the play, and continued to grow into a close

relationship

through the early 1920s, with the two often going to the theatre

together. On

one occasion they watched a performance of 'Quality Street' – of which

Barrie

commented to her: “It bored me to write it, it bores me to see it” -

and on

another they attended the first night of 'Mary Rose'. He called

her 'Tommy', inscribing

the name in some of his books he gave her, and he invited her to his

Adelphi

Terrace home on many occasions.

But what became of Lydia Lopokova in the meantime? She broke her

absence by

appearing as a dancer in New York in a show called 'The Rose Girl' in

February

1921, and in early May she appeared in Paris dancing with Ballets

Russes once

more. What she did during the period since her abrupt disappearance in

July

1919 remains a mystery, other than that she later wrote that she gave up

dancing for 18 months, which revealed nothing other than that she

remained

tight-lipped about the episode. She returned to London with Ballets

Russes in

late May 1921, and by the end of July she had danced in a dozen ballets

in that

season. Of major significance in her personal life was the frequent

attendance

at these performances by the person she had first written to in

December 1918,

the eminent economist John Maynard Keynes. The relationship

between 'Loppie'

and 'Maynard' began to get serious at the end of 1921, and they married

in

August 1925. Eventually she became a British aristocrat's wife when she

acquired the title of Lady Keynes in 1942 by virtue of her husband being

created Lord Keynes, Baron of Tilton.

Barrie continued to feature quite prominently in Lopokova's life,

however,

after her return to dancing and London. The two kept in touch by letter

and

telephone, and they met from time to time. The dancer addressed the

playwright

as 'Barrie', for, as she once wrote to Maynard, “I could not call

Barrie 'Jim'

– I never address him 'Sir' either.” A letter he wrote to her on 7th

August,

1923, is held in a collection of her letters (not accessible at the

time of

writing this article) at King's College, Cambridge, and a telephone

conversation was referred to in a letter she wrote to Maynard on 20th

January

1924: “Barrie tells me on the telephone that Massin [Lopokova's name for

Léonide Massine] coached Gladys Cooper's 'Peter [Pan]' in all her

movements,

especially on the wires! He [Barrie] is so very occupied with the

rehearsals

that I can't ever see him. Now it is 'Alice sit by the fire', but he is

well

and was expecting Nicholas [Nico Davies, presumably] to-night.”

While Lydia's letters to Maynard indicate occasional contact with

Barrie,

including reports of the odd meeting for tea or dinner, this particular

letter

seems to show that she maintained a desire to meet with him over a

period of at

least a few years during the early 1920s. Other letters showed concern

for

Barrie's health and well-being: On 22nd February 1924 Maynard, writing

from

King's College, Cambridge, told Lydia of a forthcoming performance

of 'The

Duchess of Malfi', adding, “Why don't you and Barrie come down together

for

that play?”. On 2nd March he asked her again, “Have you asked Barrie?

Dennis

[Robertson] enquired because he also had thought of asking him; but D

thinks he

will refuse partly because he always refuses things, and partly because

Cambridge may be rather haunted for him by the one who was drowned.”

Lydia

replied on 6th March writing, “I telephoned to Barrie, first in the

bath he was

(although clean I never thought he takes one), after he telephoned and I

proposed the offer to [go to] Cambridge – a drastic refusal, besides he

owns a

little neuritis.” Maynard Keynes's mention of “the one who was drowned”

would

seem to refer to Barrie's ward, Michael Davies. Michael's drowning, in

1921,

was life-changingly devastating to Barrie; this was very evident to

Barrie's

family and friends. But it seems that Keynes was confused. Michael was

an Oxford

scholar and he drowned in the river Thames at Sandford Pool, outside

Oxford.

There was no direct connection between Michael and Cambridge. For family

connections we have to look at Michael's father, Arthur, and his uncles

Charles, Crompton and Theodore, and also their father, John, all of

whom were

alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge. It so happens that Theodore also

had died

by drowning in a river (in the Lune, near Kirkby Lonsdale, in 1905) but

it

seems unlikely that Keynes would have known this.

For how long did the friendships between Barrie and the two Russian

ballerinas

last? While both dancers became British citizens and lived in England

for the

remainder of their lives, no evidence has been found that Barrie was

invited

to, or attended, Lopokova's wedding at St Pancras Central Register

Office in

1925, or that either ballerina attended Barrie's funeral in Kirriemuir

in 1937.

According to Keynes's nephew, Milo Keynes, Sir Frederick Ashton once

revealed

to him that he had heard that for some time Barrie had had Lopokova in

mind for

another play but, in itself, and even if true, this does not constitute

evidence of an enduring close friendship between the playwright and the

dancer.

As for the play, 'The Truth about the Russian Dancers' went unpublished

until

1962 when it appeared in America with an illuminating introduction by

Tamara

Karsavina. It was later published as a paperback in 1987.

Somewhere there is in existence a film of Karsavina dancing the role of

Karissima, a short film sequence which reportedly was made at the

request of

Lopokova, for no official film was made of either the 1920 or the 1926

production.

Tamara Karsavina,

centre, in 'The Truth about the Russian Dancers', 15 March,

1920

Tamara Karsavina,

centre, in 'The Truth about the Russian Dancers', 15 March,

1920

Photographs of the 1920 production were taken on the day of the

premiere, and

Barrie sent six of them to Huntly Carter, an English drama critic who

also was

seriously interested in the Russian arts. These six photographs, showing

Karsavina and other characters in the ballet, together with the envelope

addressed in Barrie's handwriting, were auctioned in Sheffield in

January 2006.

A forthcoming, as yet untitled book about Lydia Lopokova, written by

Judith

Mackrell, Dance Critic for The Guardian, is due to be published in the

UK by

Orion in April 2008. It remains to be seen whether Mackrell has

unearthed any

details which throw further light on the friendship between Barrie and

Lopokova, or on Barrie's view of ballet. In the meantime it is

reasonable to

say that, over the almost 100 years since the establishment of Ballets

Russes

in 1909, Russian dancers have not lost their special ability to give

natural

performances of technically difficult choreography, as is demonstrated

nowadays

in performances by the present day companies. As Poesio Giannandrea

wrote of a

Kirov Ballet production of 'La Bayadere' in The Spectator in 2000, “It

is the

expressive 'magic' on which Barrie commented that keeps 19th century

works

alive”.

Robert Greenham

May 2007

© http://fierychariot.blogspot.com/2007/06/j-m-barrie-and-

russian-dancers.html

OTHER

INTERESTING

ARTICLES: Next [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]