The monster of

Neverland:

How JM Barrie did a 'Peter Pan' and stole another couple's

children

By Tony Rennell

Last updated at 6:19 PM on 08th July 2008

They met in the park. With bright red Tam O'Shanters on their

heads,

little George and his brother Jack were out with their nanny and baby

Peter,

taking the air as all upper-middle-class children did in late Victorian

Britain

if they were lucky enough to live near Kensington Gardens. Then up

bounded the

toast-of-the-town, playwright and novelist J. M. Barrie, with his St

Bernard

dog.

To the boys' amazement and amusement, man and dog began play-

wrestling -

the St Bernard, up on its hind legs, standing as tall as the diminutive

Barrie.

The show over, the great man crouched down and began talking to his

young

audience, captivating them with stories of fairies and make-believe

woods, and

doing magic tricks.

So began an association that spawned one of the classic

children's

stories of all time - Peter Pan.

The boys - five in all, eventually - were the sons of a

struggling

lawyer, Arthur Llewelyn Davies, and his wife Sylvia. From that first

meeting,

Barrie became an intimate of the family, lavishing money on them for

motor cars

and holidays abroad they could not otherwise

afford.

But it was the boys he focused his attention on. Physically more

like an

older brother than a grown man, he wowed and wooed them with his

fertile,

child-like imagination, throwing himself with complete abandon into

games of

pirates and redskins and coral island castaways.

The outdoor adventures they shared, the sleepovers, the story-

telling,

all became the fantasy world of Neverland, with Wendy and the Lost Boys,

Tinkerbell and Captain Hook - tales that would endure for a century and

more.

But the truth that lay behind this child-friendly panorama was

deeply

unsettling. In a book published next week, author Piers Dudgeon - who in

previous works shone light into the shady corners of the life of

Catherine

Cookson - lays out what he calls 'the dark side of

Neverland'.

The problems he highlights are not those that have attracted

attention

in the 70 years since Barrie's death - the sexual overtones and the

physical

over-familiarity that would have observers calling social services in

today's

paedophile-conscious society.

His sexuality was not the issue. Barrie was almost certainly

impotent

and his marriage was never consummated, according to Mary, his wife for

15

years: 'Love in its fullest sense could never be felt by him or

experienced.'

Instead, his thrills came from the power dynamics of

relationships and

playing mind games with people, at which he proved a master. This was

what made

Barrie a dangerous man to know, particularly for

children.

Scottish-born, the son of a weaver, he had made his way in the

world

from humble origins. But, as a boy, he had been rejected by his mother,

cast to

one side while she grieved for his older brother, dead in an

accident.

The accident happened while ice skating, the older boy, on the

eve of

his 14th birthday, falling on the ice and fracturing his skull. Dudgeon

speculates that the seven-year-old Barrie may have been responsible,

for which

his mother could not bring herself to forgive him.

He began his story-telling as a means of getting her attention

again.

But his heart was hardened. There was no real love in him, only a

saccharine sentimentality. He knew it too, admitting openly to

having 'a darker

and more sinister' side. He learned from an early age the art of

manipulation.

It follows, then, that his meeting with the Llewelyn Davies

family and

their boys was no chance encounter. Barrie had sought it and planned

it.

He was, by nature, a stalker. As a boy in Dumfries, he would

follow the

cloaked figure of famous essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle. He

longed to

touch the great man, just to be able to boast that he had done so, but,

typically for him, never plucked up the courage.

Then, as a writer trying to make his way in London, he pursued

the

novelist and poet George Meredith, only to turn and run when Meredith

approached him. 'Throughout his life,' writes Dudgeon, 'Barrie was

driven by

hero-worship, perhaps because he felt himself to be so un-

heroic.'

Another idol he fixated on, and crucial to this account, was the

Punch

illustrator and bestselling novelist George du Maurier, one of the

social

giants of literary London. Du Maurier was the acclaimed author of

Trilby, the

story of an obsessive musician named Svengali who falls in love with

Trilby, a

carefree artist's model. He dreams of making her a great singer -

except that

she is tone deaf.

But through hypnotism, which he has mastered to perfection,

Svengali

transforms her, releasing from her lips the most exquisite music the

world has

ever known. It also makes her lips available to him. She is his

slave.

To the readers of repressed Victorian Britain, this was all too

thrilling. Trilby sold 300,000 copies in its first year (1894) - more

than

Dickens - and was the first bestseller of modern

times.

So successful were du Maurier's fictional creations that the

novel

coined not just one, but two new words in the English

language.

Trilby denotes a hat with a narrow brim and an indented crown,

as worn

in the stage version of the novel. And Svengali is a person 'who

exercises a

controlling influence on another'. Du Maurier knew what he was talking

about.

As a young art student in Paris and Antwerp, he practised hypnotism on

the nude

models he sketched.

One in particular, a 17-year-old church organist's daughter,

with 'blue

inquisitive eyes and a figure of peculiar elasticity', as he recalled,

became

his besotted plaything.

To Barrie, Trilby represented the very sort of mind-games and

manipulation that appealed to his nature. He must also have suspected

that du

Maurier had written from experience. He wanted to connect with him, for

the

mesmeric magic to rub off on him too.

But du Maurier was dead, from cancer, in 1896, just two years

after his

great literary success. So Barrie turned to the next best thing. He

inveigled

his way into the du Maurier family - and, in particular his daughter,

Sylvia,

married to Arthur Llewelyn Davies and mother of those boys in the

park.

Ever the stalker, he engineered a meeting with Sylvia and Arthur

at a

society dinner party, where he pronounced Sylvia 'the most beautiful

creature'

he had ever seen. He noticed her squirreling away sweets, which she

said were

for her boys. Barrie was in.

Then, like a cuckoo in the nest, with generous gifts and ever-

presence,

he cleverly sidelined Arthur and wheedled his way into Sylvia's

affections. His

intention was not love, but control, as he steadily stole her and the

boys

away.

They had something he craved. The boys had the du Maurier magic

about them,

the charisma that Barrie fed on, particularly those he singled out

as 'The One'

and gave his keenest attention to.

First George was the favourite, then, as he grew older, Michael

took his

place. In their ' boyishness' Barrie saw what for him was the ideal

life,

representing the free, unconfined spirit and the key to eternal

youth.

But he could never really let them be themselves; he could never

let

them go. What began with seduction of the du Maurier clan ended in

abduction.

Humiliated by Sylvia's friendship with Barrie, Arthur Llewelyn

Davies

died at 44, of a horribly disfiguring cancer of the face - followed

shortly

after by Sylvia herself, also at 44 of cancer.

Barrie, though no relation, simply assumed guardianship of the

boys on

the pretence that he had been about to marry their mother before her

death.

What is extraordinary is that no one else in the du Maurier

family made

any claim on the orphans, not grandparents nor aunts and uncles.

Perhaps they

were indifferent; perhaps they thought Barrie a perfectly fitting

father.

But to head off any objections, Barrie had Sylvia's will to wave

at them

- which he had, with consummate calculation, forged in his

favour.

She had intended her sister, Jenny, to be the guardian of her

sons. But,

with a flick of his pen, Barrie changed 'Jenny' to 'Jimmy'. Some of

Barrie's

biographers believe this was an accident and he had not altered the

hand-written will but honestly misread its

contents.

But Dudgeon, having compared the original and the doctored copy

that

Barrie made available, has no doubt that there had been skullduggery. He

writes: 'He made the boys his own and the alteration of Sylvia's will

shows

that his strategy was predatory.'

Michael was ten when Sylvia died and the most handsome of all the

brothers. Ten was the age Barrie considered perfection in a boy, and

the two

became very close, unhealthily so, according to many who witnessed their

relationship.

For all his preferred image of innocence, walking by the

Serpentine with

a rapt child hanging on each hand, friends of the boys thought Barrie

creepy.

There was something 'sinister about him', one recalled. It wasn't so

much the

fear of sexual abuse that concerned them but the domination he

exercised over

such young and impressionable minds and

personalities.

Nor did his power stop there. Barrie's malignant influence also

extended

into the rest of the du Maurier family. He struck up a firm friendship

with

Gerald, Sylvia's actor brother and the boys' uncle, insinuating himself

into

his household too.

Four-year-old Daphne, the second of Gerald's three daughters -

destined

to be a writer every bit the equal of Barrie - was drawn into his make-

believe

world, in which she was expected to behave like a boy, following the

lead of

her male cousins. Introverted, withdrawn but blessed with a vast

imagination,

she was a child of bewildering complexity and every bit as manipulative

as

Barrie, as her later life demonstrated.

She adored her father with a passion that, returned by him, may

have

edged too close for comfort to incest. Or maybe, when she confessed to

such

things, she was simply making it up. With master-storytellers, you can

never be

quite sure.

Not yet 16, she had an affair with a philandering cousin 22

years older,

then, when sent away to a finishing school in France, claimed to be

sleeping

with the thirty-something lesbian principal. Later, there would be a

marriage

and children, but also lovers, two of them women.

She claimed, not a little resentfully, her sexual orientation

had been

confused by her childhood part in Barrie's 'boy-cult'. He had got

inside her

mind, toying with her sense of self, just as he had the Llewelyn Davies

boys

and their mother.

But those mind games also gave her perhaps the greatest

character in her

fiction, the unseen but all-pervasive Rebecca, someone outside the

normal

conventions, ruthless, demonic, supernatural - and exercising the same

sort of

predatory control on all around her as had Barrie, Daphne's

mentor.

Daphne's life was never straightforward. She had a mental

breakdown in

1957. The Llewelyn Davies boys also suffered hugely because of the hold

Barrie

had over them. George went to war to escape his influence and was

killed in the

trenches in France in 1915. Jack suffered from

depression.

Michael drowned clasping a fellow undergraduate, another 'lost

boy', it

seems, in a pool near Oxford in 1921 in what was described at the time

as a

tragic bathing accident, but may well have been a suicide

pact.

Dudgeon thinks it may even have been inspired in part by Peter

Pan's

assertion that 'death is an awfully big

adventure'.

Peter also killed himself, beneath the wheels of a train. No

wonder D.H.

Lawrence was moved to say: 'J.M. Barrie has a fatal touch for those he

loves.'

Only Nicholas, the youngest, seemed to have emerged relatively

unscathed

and with an untarnished view of Barrie.

'I lived with him on and off for more than 20 years,' he

said, 'alone

with him in his flat for five of these years, and never saw a glimmer of

anything approaching homosexuality or paedophilia.

'He was an innocent, - which was why he could write Peter Pan!'

As if

that were argument enough.

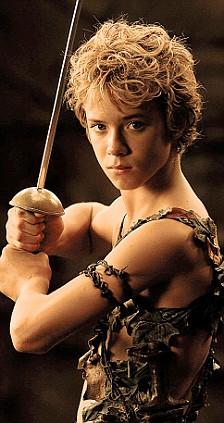

But here, with Pan, is where Barrie pulled off his most masterly

manipulation. Peter Pan, his greatest invention, has been woefully

misunderstood over the generations, taken as a fairy tale, a harmless

pantomime, a Disney adventure in a land of innocent

children.

But Peter was no hero; he was a demon boy who, like Barrie, had

no love

in him. He stole children from their beds and killed without

conscience - and

that was how Barrie wanted him to be.

But the play (which is how it began; the book came later)

changed from

the moment of its first rehearsal. Captain Hook was inflated to boost

the role

of the actor taking the part - none other than Gerald du Maurier,

Sylvia's

brother.

He did such a good job that the evil Hook assumed a larger

presence on

stage than intended. As a result, when Peter Pan defeated the baddie,

the demon

boy was taken to be a goodie.

But this was not how Barrie ever conceived him. In the

playwright's mind,

Peter was cunning and sly, an anarchic character suffused with sadness.

As a

baby, he had flown out of the nursery to play with the fairies in the

park, and

then, when he tried to get back home, he found the window barred and

his mother

nursing another little boy.

He returned to his fantasy world only because the real world had

rejected him - which was just how Sir James Barrie, for all the honours

heaped

on him, felt about himself.

He never found the magic touch that he so assiduously sought for

himself

by association with the du Maurier family - and all the magic that

Peter Pan

brought to generations of children never seemed enough for him.

The 'never' in

Neverland was finding his own happiness. He himself was the ultimate

Lost Boy.

Part

of the Daily Mail, The Mail on Sunday, Evening Standard & Metro Media

Group

© 2008 Associated Newspapers

Ltd

OTHER

INTERESTING

ARTICLES: Next [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]